This is the ninth article cataloguing the series of Etchings by John Sell Cotman published in 1811. Here, plate 6 returns us to York, to sketch in the grounds of St Mary’s Abbey.

John Sell Cotman

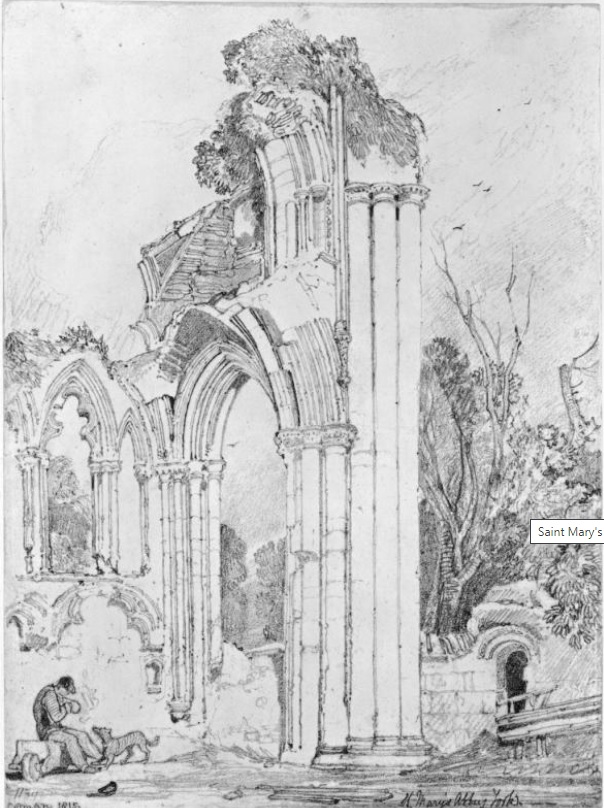

St Mary’s Abbey, York, 1810

Private collection

Photograph: Professor David Hill

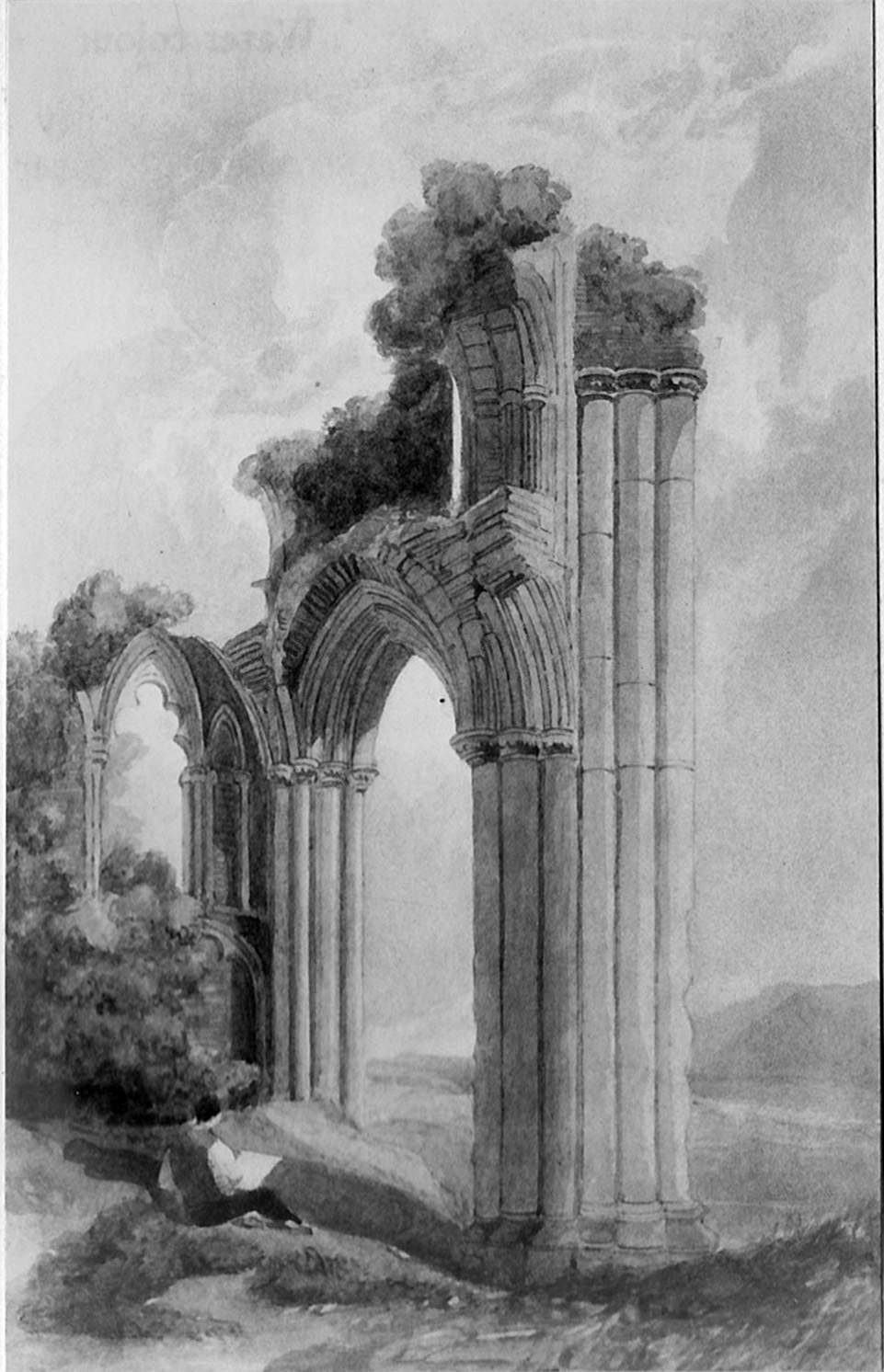

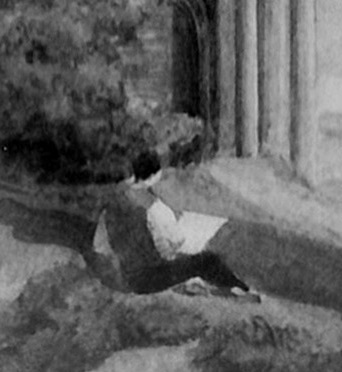

This is an impression of a copper-plate etching of an upright architectural subject featuring a tall, ribbed, gothic arch, with a view through to a grassy mid-distance flanked by trees. The arch is flanked on the right by a tall multi-columnar pier, its right three columns reaching to twice the height of the arch. A wall extends to the left carrying an open pointed-arch window, flanked by two blind lancets. The window tracery is missing except for the tricuspid upper part. Seated in the foreground is an artist drawing on a substantial sheet resting on his knees. He wears dark trousers and a light-coloured waistcoat with striped front panels. There is a leather roll on the ground by his left elbow, probably containing his drawing materials.

The plate was etched by Cotman and dated 3 October 1810 for his first series: ‘Etchings by John Sell Cotman’. This was issued to subscribers in parts, and the present subject was published as plate 6 in the complete edition as published in 1811. It is the first large plate in the published order, the third in date order, and the sixth in the bound order. It lacks detail in the sky, and is perhaps over-prettily vignetted, but has splendidly inventive use of the burin. There is considerable scratching of the plate especially to the lower left, probably caused by wiping, and some smuts on the tall columns at the right. It is interesting that the ‘3’ is reversed in the inscribed date. This rather betrays Cotman’s inexperience in the medium, and there are many such mistakes in his earlier etchings.

Right click on either image to open full size in new tab. Close tab to return to this page.

The subject is the arch between the north aisle of the nave and the north transept of St Mary’s Abbey. York. The abbey was founded in 1086 on a site just outside the western wall of the city, stretching north from the left bank of the Ouse. The original church was destroyed in a city-wide conflagration in 1137 and although the church was rebuilt, it completely replaced by a the surviving Gothic structure in 1270-94. At its dissolution in 1539 it was the richest house in the north. Over the next two hundred years it was progressively plundered until by the later eighteenth century this arch was the most substantial part of the whole church to survive.

The main cluster of columns is the north-west pier of the crossing. It should be noted that the etching gives the subject in its true orientation. It is the first large plate in date order in which Cotman puzzled his way through the difficulties of reversal inherent in the etching process. Simply put, the image on the plate prints on the paper as a mirror image. Etching the subject in reverse so that it will print as a positive image requires practice and process. Both earlier larger plates, North Creake and Rievaulx [both later in the published order] are reversed, as are the preceding smaller plates of The Manor House, York and Duncombe Park. The smaller plates of Valle Crucis and South Burlingham give their subjects the right way round.

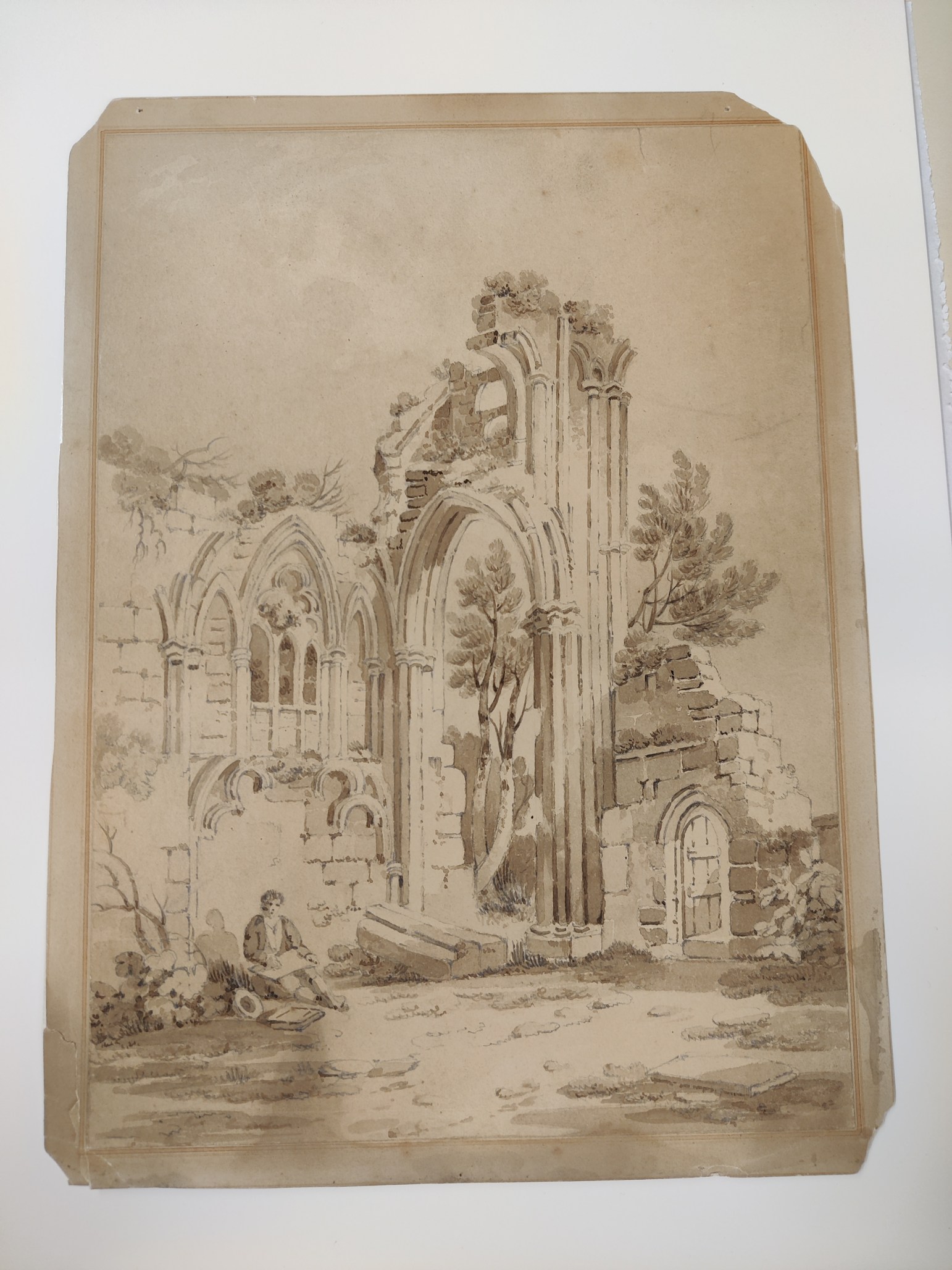

Cotman visited York at the beginning of his first tour to Yorkshire in 1803. He was travelling in the company of fellow artist Paul Sandby Munn, in whose house in London he was then living. I wrote about the tour in Cotman and the North (Yale University Press, 2005) where I surmised that the two arrived in the city on the 2nd or 3rd of July. We know something of their sketching activity from dated drawings, and although no sketch of the subject by Cotman survives, there is one by Paul Sandby Munn dated 4 July 1803.

It seems possible that the two artists sat side-by side. In Cotman in the North I wondered to what extent the two artists might have shared material. Cotman was living at Munn’s house in London, where the latter ran an extensive business selling art materials, manuals, drawings and prints. Comparison of the treatments, suggests that Munn’s drawing appears generally accurate in detail and although Cotman’s etching is more picturesque, it contains nothing substantive that could not have been elaborated from Munn’s sketch.

The composition provoked further work by both artists. One watercolour version by Cotman was once in the collection of Sir Henry Nicholas Holmes (1868-1940), Lord Mayor of Norwich in 1921 and 1932.

This is now known only through its reproduction in the privately printed catalogue of the Holmes collection published in 1932, where this was no.18, Ill IX. The description in that catalogue remarks that ‘In the foreground is a figure in a deep blue waistcoat’, which sounds an attractive detail. Miklos Rajnai’s notes in this catalogue of early drawings by Cotman, published by the Castle Museum, Norwich in 1979 (no 24 n.14) notes two watercolour copies by pupils, but makes no specific mention of the Holmes watercolour.

Courtesy of the Huntington Art Museum, San Marino, California

In 1815 Cotman reworked the composition in a graphite drawing at the Huntington Art Museum at San Marino. California. It makes a strikingly different impression to the etching. The architecture is regularised, all the orthogonals are rationalised and the masses sit much more squarely on the ground. Cotman was by this stage an accomplished draftsman of architectural and antiquarian subjects. He was also an experienced printmaker both of line and softground etchings, and it is possible that this drawing was made in that context. He was also well established as a drawing master and maintained portfolios of drawings for his students to study and copy. It has not been previously noted that the Huntington drawing seems to bear a number at the lower left inscribed just above the signature. This appears to read ‘1139’, although the third digit is imperfect and might alternatively have been intended for a ‘5’. Over the years Cotman numbered several thousand drawings in this series. A good deal of work remains to be done on the numeration.

Many of his compositions from this period were designed specifically to appeal to pupils. In this drawing Cotman turns the remains of St Mary’s into a grand garden ornament, with a boy gardener complete with dog and barrow. He also designs different areas for the eye to explore, sometimes with promise, as in the long avenue at the centre, or with mystery and even menace, as in the dark portal at the right, or the dark blasted trees beyond. All of this is poetic invention, rather than any statement of topographical fact.

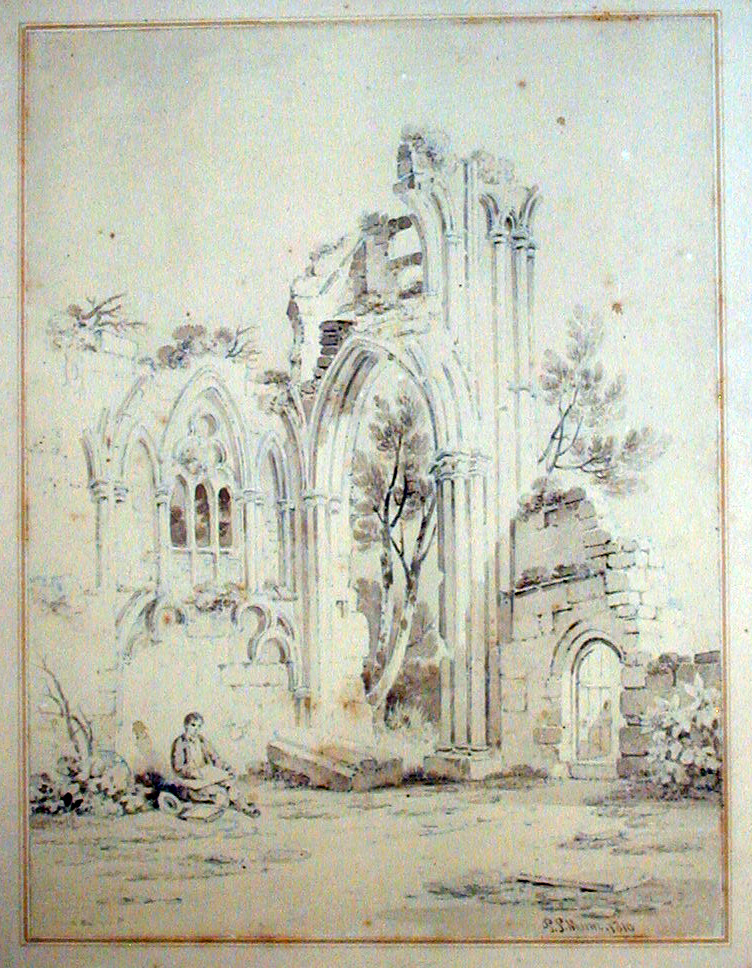

Munn also maintained his own interest in this subject over a number of years. York City Art Gallery has a watercolour of the same view, also featuring a seated artist, albeit different to Cotman’s, signed and dated ‘P S Munn 1810’ (R.1498) I am grateful to Theodore Wilkins at York Museums Trust for letting me see an image of this. It is by no means a substantial production, and might well be a studio production.

The Huntington also has a second drawing of this subject in their collection which records the identical Paul Sandby Munn composition to that at York. This, too, appears to be a studio work, but the handling is perhaps a little more crisp than that at York. At the very least it does appear that it was a popular composition with Munn’s clients. I am grateful to Ming Aguilar at the Huntington for locating these drawings, and for helping with images.

In addition to the views from the nave, Cotman and Munn must also have sketched the view from the north transept. No on-the-spot sketch by either artist survives, but each made studio drawings of the subject.

It is likely that some of these drawings might be identified with recorded exhibits. In 1809 Cotman showed two compositions of ‘St Mary’s Abbey, York’, nos. 7 and 9 at the Norwich Society of Arts. We cannot be entirely certain what these were, but it seems a reasonable surmise that one showed the same aspect as the etching, and the other showed the view from the transept. Nor do we know what form the exhibits took, whether pencil drawings or watercolours. Cotman used this exhibition to promote the idea of a library of drawings that students might hire in order to study and copy them. A few exhibits were captioned explicitly as ‘The drawings marked thus* are from his Circulating Portfolios, now open to the public on the plan of a Circulating Library.’ Both drawings of St Mary’s were so marked.

Few of the 1809 exhibits from the Circulating Library are known today with any certainly, but one that might be identified as no.169 ‘Fish Swills, Rudder etc’ with a substantial watercolour dated 1809 at Norwich Castle Museum (NWHCM : 1951.235.151 : F). From this, it would appear that Cotman populated his new library with some proportion of high-quality and densely coloured watercolours. The 1809 exhibits then might have consisted of the Holmes watercolour (see above) representing the view from the nave, and there is a perfect candidate for the transept view in a watercolour at Birmingham Museums and Art Galleries.

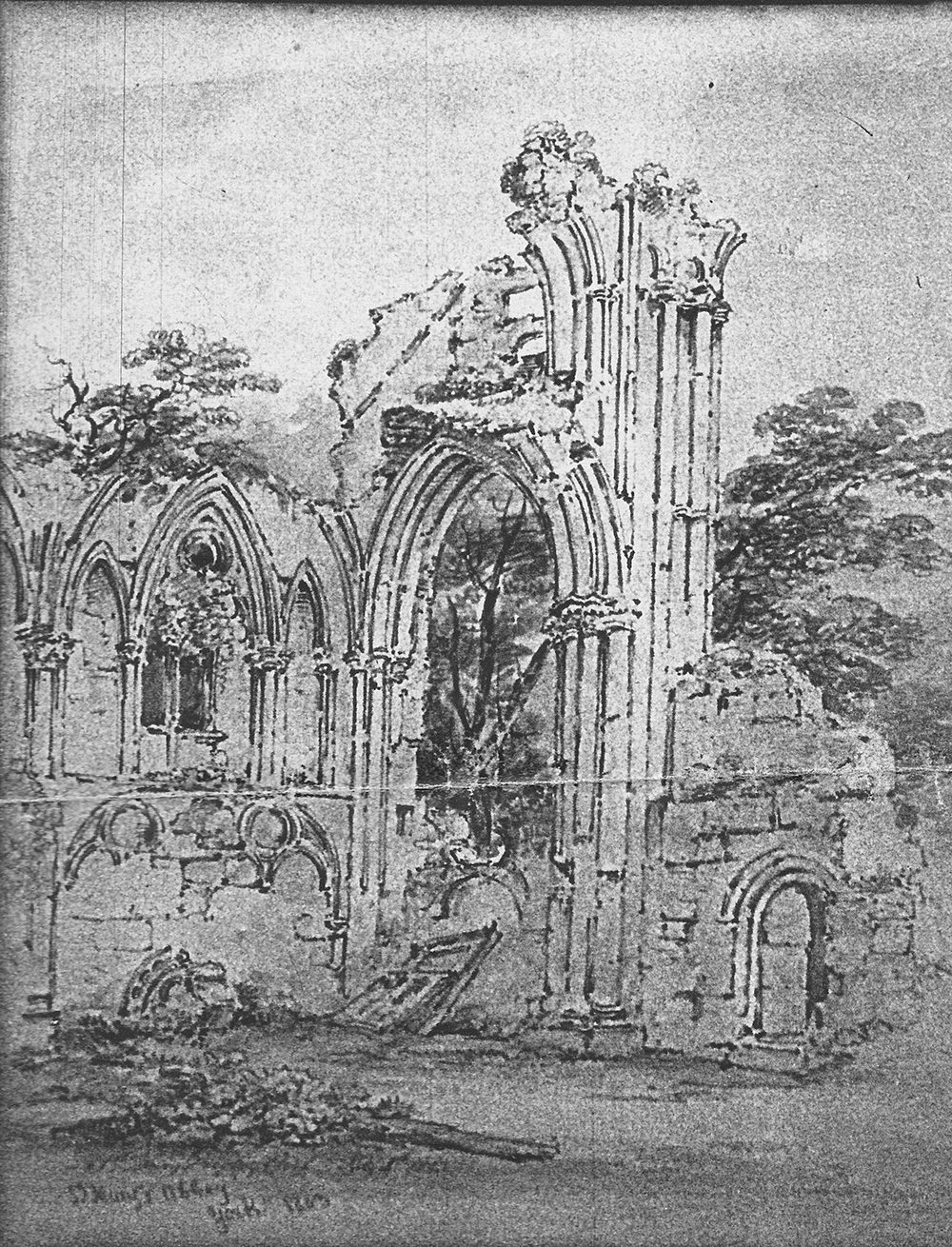

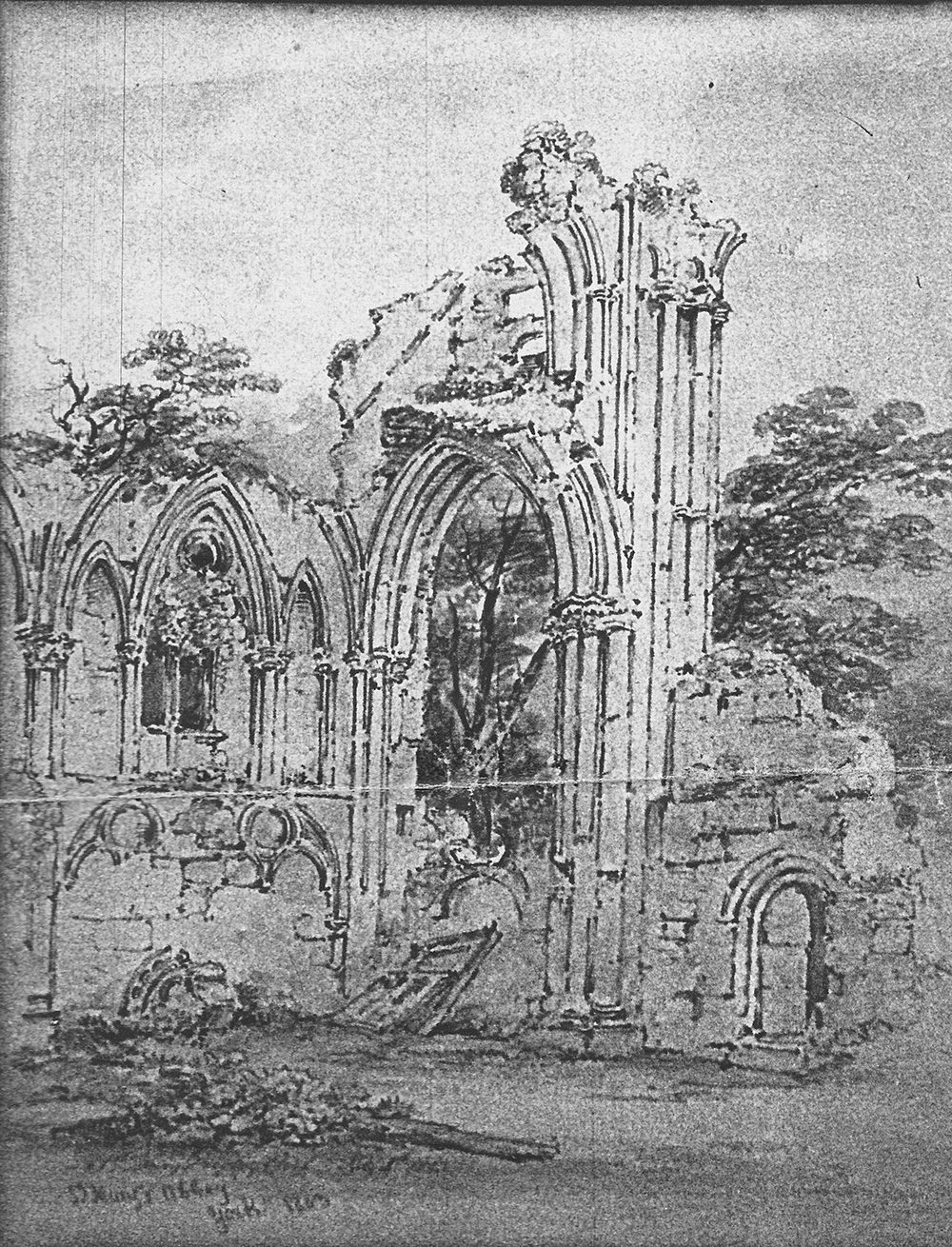

St Mary’s Abbey York, c.1808

Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, 1953P119

This in many ways might be considered one of the most remarkable compositions of this part of Cotman’s career. In it he completely eschews any sense of decorative elaboration, and eliminates anything topographically contextual. So the arch is recast as a solitary sentinel in an apparently lonely country. St Mary’s is adjacent to York city centre, but anything approaching contemporary bustle and business is banished. Construction is limited to what can be fashioned from a few timbers stacked against a wall. If this was one of the exhibited works then it would have been seen as sufficiently uningratiating as to be confrontational: Its simplicity a repudiation of the established demands of contemporary taste. As I explored in Cotman in the North, after his sojourns in Yorkshire, Cotman’s work took quite a radical turn against the inessential. Furthermore, he persevered with his quest, even though it was widely pointed out that the market would almost certainly fail to thank him.

The next references to Cotman and St Mary’s are in relation to the etching published in 1810 (see above), and an exhibit of ‘St Mary’s Abbey, Yorkshire’ at the Norwich Society of Artists, 1811, no.56. Once again we cannot be certain what the exhibit might have been but the catalogue stated: ‘The Drawings and etchings are chiefly intended for his Miscellaneous Etchings and his Illustrations for Blomefield’s Norfolk’. The latter was a new project [treated elsewhere in www.sublimesites.co] , which was to occupy him for the next few years, but twenty-four of the thirty-four exhibits in 1811 were subjects from the Miscellaneous Etchings. Studying the list more closely, we can see that many of the Norfolk subjects are described as ‘sketches’, but none of the etched titles have any such qualification. The inference must be that Cotman showed more-or-less the whole suite of etchings that he had just published. Two early efforts were missing, Beeston Priory, and the North Portal of South Burlingham Church, but St Mary’s was offered sixth in the running order.

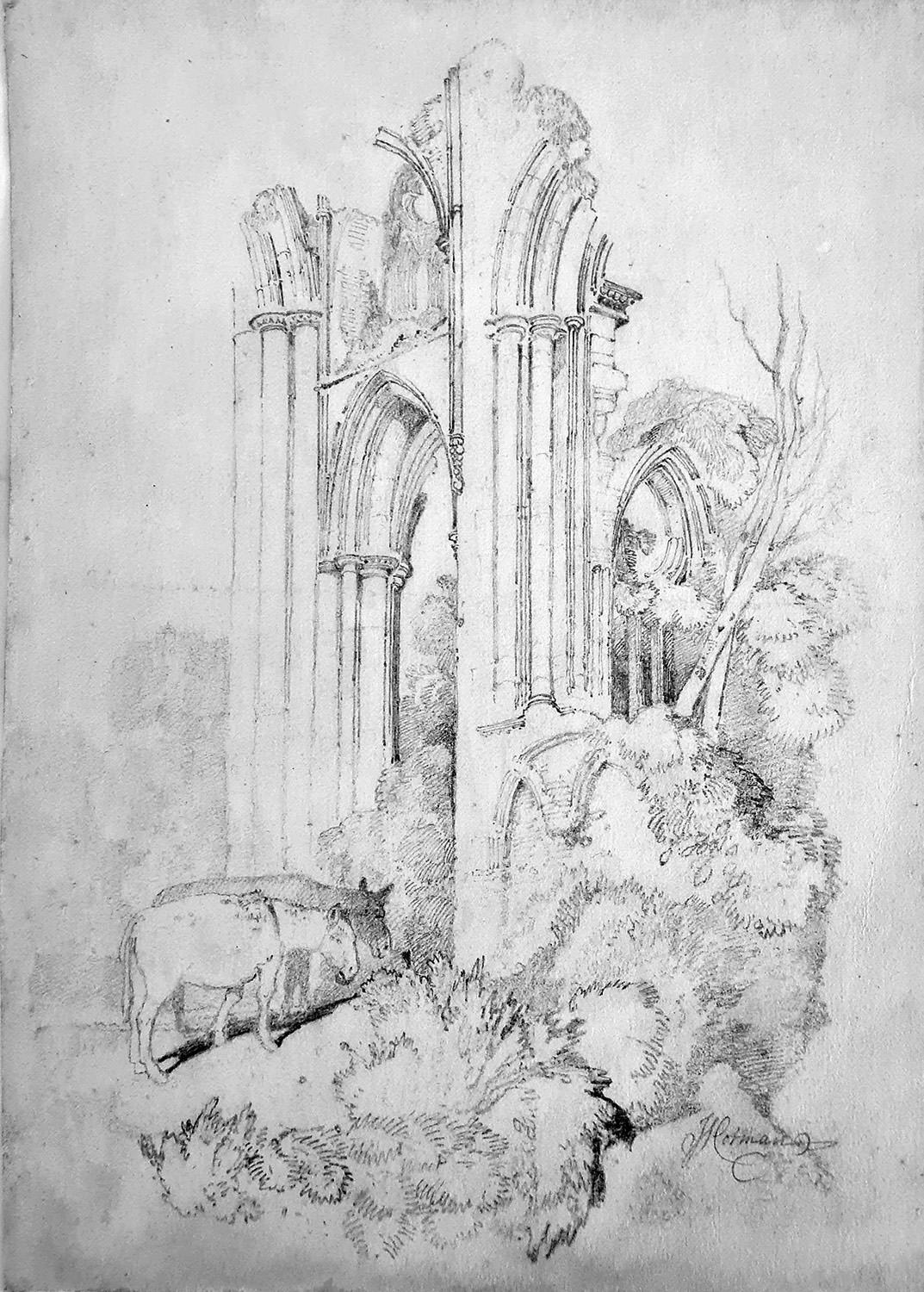

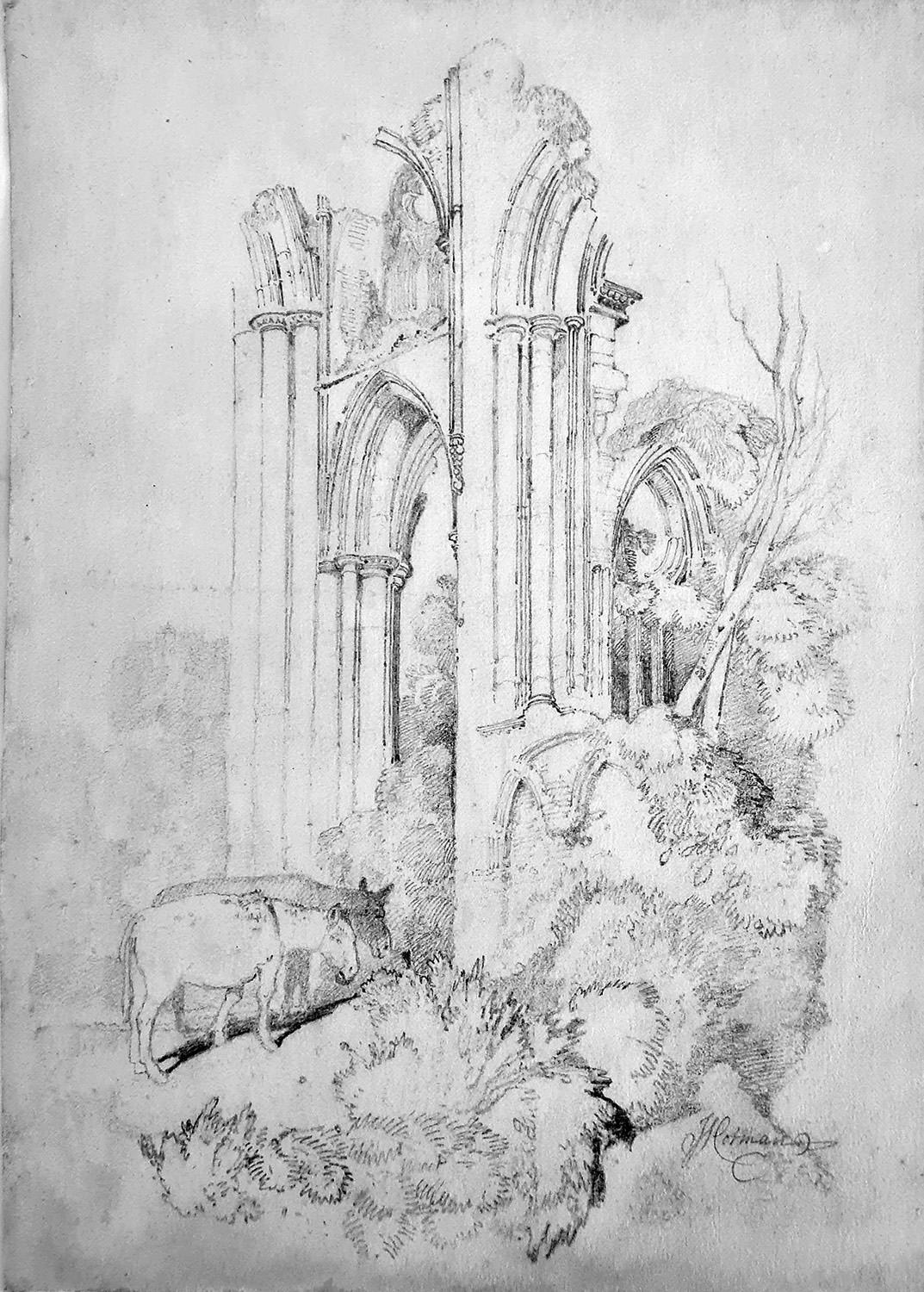

St Mary’s Abbey, York, c.1811

Pencil on paper, 373 x 265 mm, 14 3/4 x 10 1/2 ins

Alex Puddy Fine Art (2023)

It is perhaps hereabouts in the sequence of production that we might place a pencil drawing of St Mary’s Abbey York, as seen from the Transept, which reappeared from the Cotman family collection onto the market at Dawson’s auctioneers of Maidenhead on 23 May 2023 as lot 199. The sale comprised numerous items from the collection of Alec G Cotman. This particular example had descended from John Sell Cotman’s nephew, the artist Frederick George Cotman. It was bought by Alex Puddy Fine Art

This is a highly controlled studio pencil drawing, similar in overall conception and approach to the etching published in 1810. Unlike, however, other pencil drawings made as preparatory studies for watercolours or etchings, this has a self-conscious quality, preened somewhat for display. If it is not to be identified with any of the recorded exhibits in this period, it must certainly have been made for presentation or sale. The rather flamboyant signature suggests a degree of showmanship, and perhaps even of swagger.

The forward-leaning script is unusual except in Cotman’s particularly positive periods. 1811, when he moved to Yarmouth, is a period of great optimism, as is 1824, when he set up his great house in Norwich, and again 1834-5 when he moved to London to take up a Professorship at King’s College School. Similar forms of this signature occur in some of the Miscellaneous Etchings, and Cotman experimented with a florid script in many of those works.

The etched signatures, however, must have been done in mirror-writing and it would be better to find a comparable autograph example from this period.

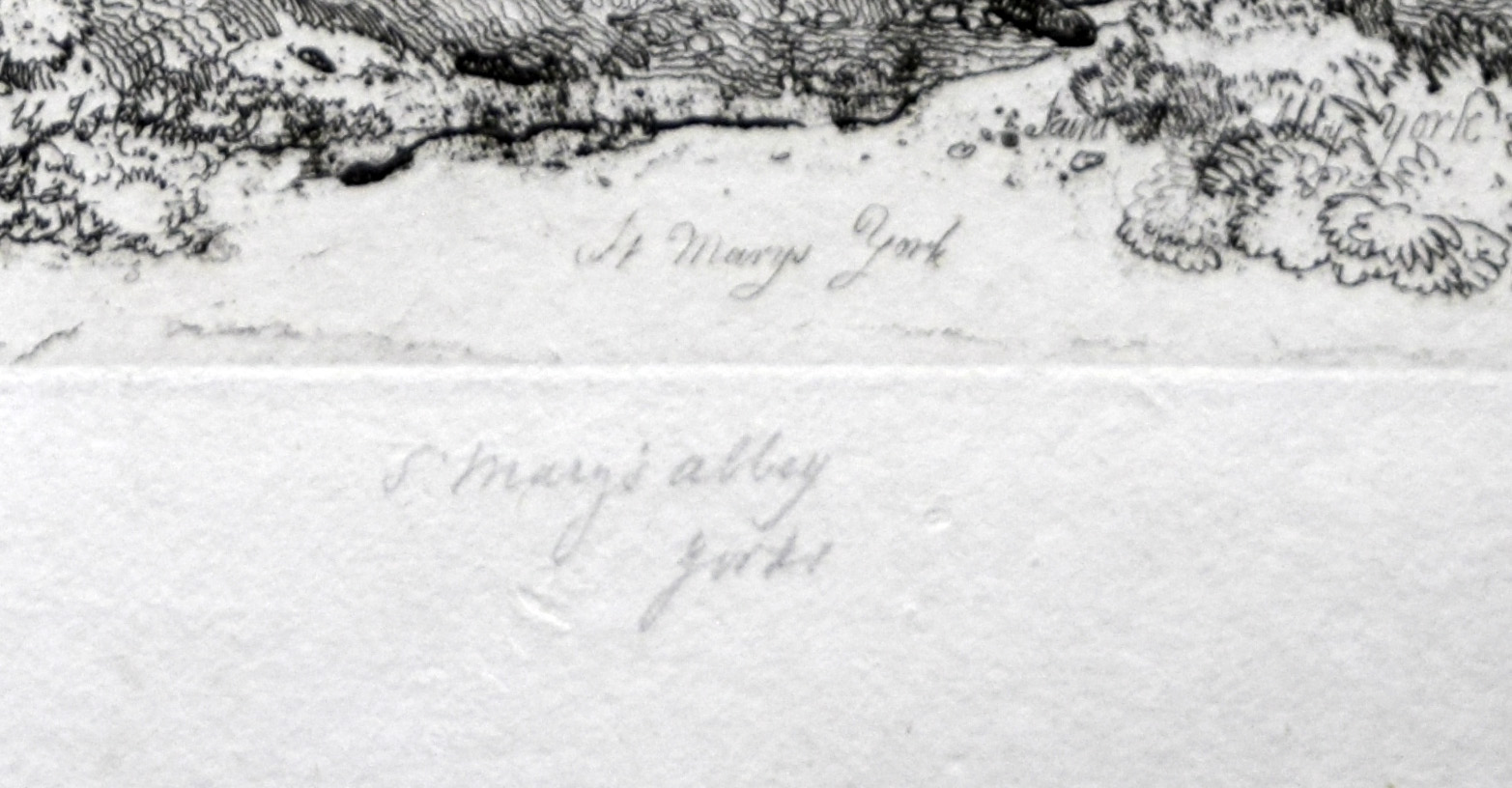

On the verso is an inscription giving the subject ‘St Marys Abbey/ York’. It is by no means impossible that this is in Cotman’s own hand. It compares very closely with the engraved title inscription on the published etching.

On the other hand it does not compare that closely with the pencil inscription on the published print. I have always assumed that the latter was in Cotman’s own hand, but that is not proven. It might require a professional graphologist to resolve this issue.

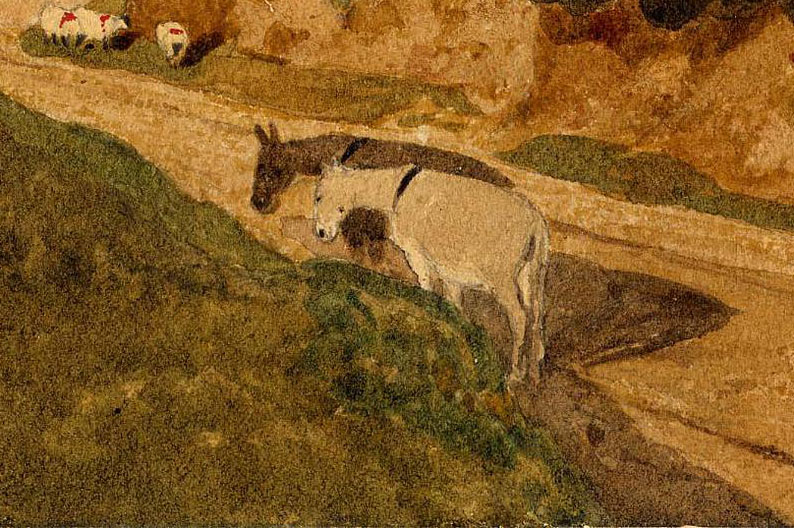

Perhaps the most remarkable element of this composition is the pair of donkeys to the lower left. Their inclusion is clearly not gratuitous; Cotman intended us to consider and reflect upon them. In the context of the city of York, they would clearly have been hard-working animals, possibly used in coal haulage or the carriage of market goods, and are here enjoying some rare rest and recuperation. In reality they would have been unwelcome interlopers browsing in St Mary’s gardens. In association with the architectural setting, they clearly allude to their Christian significance. The dutiful mount of Christ, representing service and loyalty, or the poor beast (Numbers 22) abused by his mount, Balaam, for stopping in the road because an angel of the Lord blocks the way. Balaam is blind and beats the donkey for seeing what he cannot, before the Lord intervenes. On a more general level donkeys stand for hard work and humility, honesty, diligence, and fortitude, and perhaps goodness all too frequently abused.

Cotman clearly set some store by them, for the same donkeys appear in a c.1810 watercolour of Buildwas Abbey at Leeds Art Gallery (1929.017) and, in reverse, in an 1810 exhibited watercolour of Mousehold Heath at the British Museum [1902,0514.20]. It may be remarked that there is a rather greater and more sensitive sense of naturalism in the treatment of the animals in the St Mary’s pencil drawing.

The drawing projects a strong sense of care in the detail, but close comparison with the surviving architecture reveals many points of discrepancy. One of the principal divergences occurs in respect of the arch above the main arch. Cotman shows this as being open, but it is in fact blind, and the tracery differs. There is another significant difference in the nave window to the right of the composition, and yet another with regard to the blind arcade of the transept below. Cotman got into a complete muddle with this, and it seems plain that whatever sketches from which he worked let him down in these areas. Cotman took pride in the quality off his observation, so would have been mortified to find himself in error. He was never inattentive in front of his motif, so the differences here remain something of a mystery. These areas might very well have been obscured by ivy, but then one is forced to wonder why his sketches did not tell him that. Whatever the answer, we should not be too eager to condemn. Photography makes such record-taking effortless, but also mindless. Drawing is an altogether different proposition. On site, it is hard enough even to see the detail correctly, let alone comprehend its complex forms, relations and proportions well enough to lay it out on paper. Only a trained architectural draftsman would have the requisite skills and patience, but no requirement at all for the still more difficult quality of art.

Cotman repeated the composition in a fine pencil drawing at Te Papa, the National Museum of New Zealand. This was also unknown to me when I wrote Cotman in the North in 2005, and I only became aware of it in 2021 when Te Papa put its collection online. In the original draft of this article posted in 2021 I described it as ‘an important early work.. and a tour-de-force demonstration of his superlative delicacy with the pencil at this period’. I then thought that it must be dateable to c,1804-5 in line with several fine drawings, all about the same size of 14 ¼ x 11 ins, including Rievaulx Abbey (Tate Gallery, T00973), Fountain’s Abbey (Norwich Castle Museum, NWHCM : 1951.235.482 [dated 1804]) and Howden (Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut, USA, B1975.2.507). The appearance of the c.1811 drawing has occasioned a complete rethink of the likely date.

The Te Papa drawing was clearly intended to be shown. In comparison to the c.1811 drawing, however, its style is much more mature, and a still more virtuoso performance. The use of graphite is soft and textured, much more in keeping with his drawing style of the 1820s. In 1823-4 Cotman effected the move from his modest house in Southtown, Yarmouth, to a much larger house on the Bishop’s Plain in Norwich. Here he planned to set up as the grand master in the city, and he prepared a suite of new drawings with which to impress his public and set before his pupils.

He announced his return to Norwich with a fanfare. In 1824 he showed no fewer than fifty-two works at the Norwich Society of Arts. He styled himself ‘Cotman, Mr. J.S., Drawing Master, St Martin’s at Palace. The Drawings marked * are specimens from the folios which Mr Cotman dedicates entirely to the use of his pupils.’ Amongst them was no,93 *St Mary’s Abbey, York’ and that must certainly be identifiable with the Te Papa drawing.

As fine a drawing as it undoubtedly is, it is perhaps doubtful that its pale, and rather modestly-sized presence, would have made a lot of impact in a large exhibition full of much more demonstrative paintings. Cotman had advertised himself in the catalogue as ‘Drawing Master’, and implicitly puffed his own primacy in that department. The claim was widely understood to have even greater significance than merely artistic. Drawing had been long considered in Cotman’s circle as being expressive of moral clarity and intellectual purity (see e.g. Cotman in the North, pp.20-1), and its tuition conducive to the development of such qualities in the pupil. In drawings such as this Cotman was attempting to trade on these principles. The trouble of course, as we frequently have had cause to observe, being that most buyers in Cotman’s market tended to gauge art against measures of weight and volume.

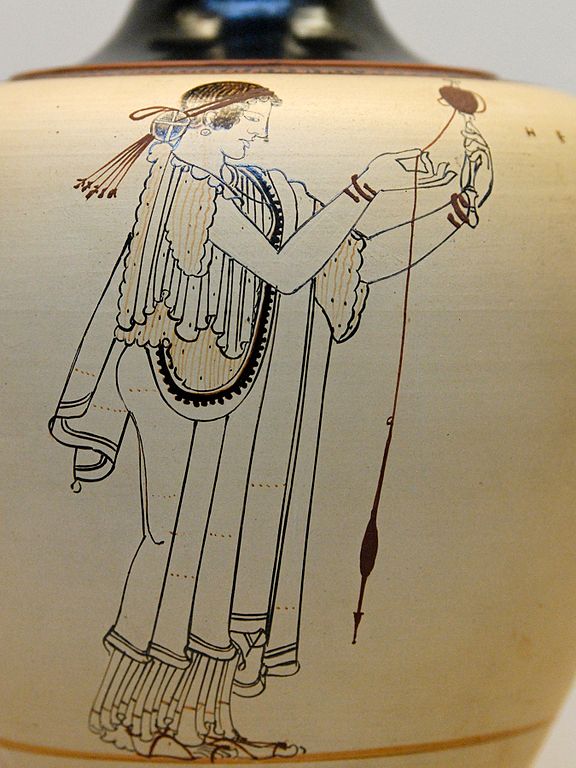

The special feature of the Te Papa drawing is its central figure of a girl spinning wool on a hand distaff and spindle. This is an exceptional conception and worth giving attention for its beauty alone. It is, however, jarringly anachronistic. The technique depicted dates back to the Neolithic. It may be seen on Greek Bronze Age vases.

Norwich had been a major centre of wool production since the middle ages, but hand spinning in this manner was long outmoded. The spinning wheel was in use by the eleventh century and dominated cottage production until the eighteenth century. After the invention of the spinning jenny and spinning frame in the mid eighteenth century, however, spinning moved into factories, and although cottage spinning never completely disappeared, by the early nineteenth century it was a decidedly marginal activity. Cotman is deliberately offering a foil to consider against contemporary industry.

St Mary’s Abbey, York, 1803

Pencil and watercolour, 311 x 212 mm

British Museum, London, 1889,1218.12

The same composition was equally important to Munn., Perhaps soon after their visit in 1803, Munn painted a fine and frothy watercolour at the British Museum. Miklos Rajnai noted in 1975 that this is inscribed with the date 4 July 1803, but that is not noticed in the current online catalogue of the British Museum’s collection. The inscription in question can be found at the lower right, partly hidden by overpainting. My reading of the date would be ‘July 5th 1803’

The date and the overpainting might suggest that the pencil work was done on the spot and the watercolour added later. But if that were to be the case, it would be mystifying that the detail is mistaken in just as many ways as Cotman’s drawings. Munn invents a buttress to the left of the arch, and, as Cotman shows the arch above to be open, rather than blind – although his detail of the tracery does correspond reasonably well. Munn likewise gives the aisle window a considerable amount of detail, and he and Cotman do largely agree in that respect. We might reasonably conclude from their agreement that although the tracery has now gone, both artists give a reasonable account of what they found there in 1803. Finally, however, Munn completely reinvents the blind arcade on the west wall of the transept. Here it is transformed into a passageway to the space outside the wall of the north aisle. He goes so far as to render this all the more plausible by devising a few trees to be seen at the far side.

St Mary’s Abbey, York, 1812

Lithograph

York Art Gallery, YORAG 2002.10.55

Finally, Munn was inspired (perhaps by Cotman’s own efforts) to translate the composition into a print. York has two impressions dated 1812 (YORAG : R3968 and YORAG : 2002.10.55, the latter mis-read as ‘P.P.MURN’). It was no.3 in a series of six ‘Etchings on stone’ that Munn published in that year. Rather than line-etching however, Munn chose the medium of lithography, which effectively transmits the qualities of graphite drawing. His own inexperience in printmaking, however, is betrayed by the fact that he was unable to reverse the composition so that it would print the correct way round. As we have seen, Cotman’s etching of St Mary’s was one of the first in which he addressed that problem. Munn’s work might have been a spur to Cotman in terms of his own working with more expressive forms of printmaking, for soon after he embarked on an extended series of softground etchings.

Returning to Cotman’s published 1810 etching, it seems natural to wonder why he chose this particular composition. It cannot have been for any intrinsic importance amongst potential architectural subjects in York. The city teems with significant subjects. Cotman even drew one of them; the Ouse Bridge, but he seems to have rejected most of the others, including York Minster.

It is instructive to consider Cotman’s approach in the light of that of his slightly older contemporary, J.M.W.Turner. His approach by contrast seems architecturally gargantuan. He sketched in York in 1797 and I reproduced most of his subjects in Turner in the North (Yale UP 1996). In a visit of no more than a few days, he recorded the Minster inside and out, made two detailed sketches of the Ouse Bridge, took St Mary’s in detail and from the river (simultaneously taking in Lendal Tower, much of the town AND York Minster), a view of the town, Minster and walls, and finally a picturesque street scene.

Cotman by contrast reminds me of Ruskin’s famous self-discovery that his mind had not room enough to engage properly with anything beyond details. Here fifty years before that, Cotman’s takes his stance on equally restricted ground.

The figure in Cotman’s etching, is clearly intended to represent his whole practice as a draftsman. Unfortunately just at the point where he needed a particularly well-expressed figure, his inexperience in the medium of etching let him down.

The figure in the etching suffers from a seriously under-resolved head. Cotman has failed to define the outline from the background, nor to resolve the form. At true scale the eye attempts to construe the shape as a wide-brimmed hat with a white band, but under the magnifying glass this dissolves into uncertainty. The first impression does, however, appear to be correct, for the figure in the Holmes watercolour (the quality of the reproduction notwithstanding) does appear to wear a dark hat with a wide, light-coloured brim.

Bohn 1838 impression with revised head

When in 1838 H.G.Bohn republished the plate in his two-volume edition of ‘Specimens of Architectural Remains in various Counties in England, but especially in Norfolk. Etched by John Sell Cotman’, the head had been ‘improved’. At least it now stands out distinct from the background, but sadly, shrunken to about half the size it ought to have been.

Detail of Cotman’s original with blank areas

On the whole, however, most of Bohn’s interventions do seem to have been mostly positive. Here he intervened in the blank areas of the columns and masonry to add areas of shading to increase the impression of work, thought and finish, and he also burnished away the various smuts and scratches that accumulated through Cotman’s inexperienced handling of the plate.

Detail of H.G.Bohn’s 1838 version, with added shading

These refinements do make Cotman’s 1811 plate seem unfinished. Cotman was presumably conscious of this shortcoming, but too technically inexperienced to trust himself to reground and re-etch the plate. To do so would be to risk losing everything that he had achieved in it thus far. We will hear of exactly such a catastrophe in relation to a later effort of St Botolph’s, Colchester (Plate 24).

As the series developed Cotman sent prepublication copies to his Yorkshire friend Francis Cholmeley of Brandsby Hall, near York. Cholmeley was assiduous in showing the various plates to York booksellers and acquaintances to drum up subscribers. Although he does not mention St Mary’s specifically, he does comment ‘by the dates you improve as you go on. There is a want of delicacy and effect I think in some of the earlier ones, particularly some of the gothic arches’ (Letter of 24 February 1811, quoted Cotman in the North, 2005, p.162). On 16 April he advised: ‘The only thing I could wish otherwise now (and perhaps I am wrong) is that you would put in skies in order to give the whole more the appearance of a finished piece’ (p.163). Cotman must have been well aware of the necessity of skies; in the Birmingham watercolour of St Mary’s, indeed in pretty much all his work in watercolour up to now, it provided, as Constable recognised, ‘the chief organ of sentiment’. It was only in the later plates of this series, however, that he felt confident enough to add a sky. The earliest is St Botolph’s Priory, Colchester, dated 20 February 1811, but as we will see that only succeeded after the first attempt was ruined.

Cotman must have been all-too-aware of his failures, imperfections and hesitations, but let the record stand. This makes the series all the more valuable as a document of a struggle of coming to grips with a medium. A record of a process calculated as he said ‘to shew talent’. Like many artists of the period, he is offering a book of drawing, but unlike the others, his is frankly confessional, and in his exposure of the trials and tribulations of his own creative process all the more intimate as a result. Sometimes, we may also find that his smallest details can hint at his core concerns. Here we might finish by noticing the care invested in one such incidental detail. On the ground behind the artist we can make out a draftsman’s roll. This is a leather strip with pouches into which he could slip his pencils and gravers and perhaps brushes. Their stocks are made out with painstaking care, the very instruments on the mastery of which his whole livelihood was staked.

Summary of known states:

First published state

As editioned by Cotman for ‘Etchings by John Sell Cotman’, 1811.

Line etching, printed in brown/black ink on soft, heavyweight, off –white, wove paper, image approx. 285 x 195 mm on plate 314 x 203 mm on sheet 474 x 340 mm.

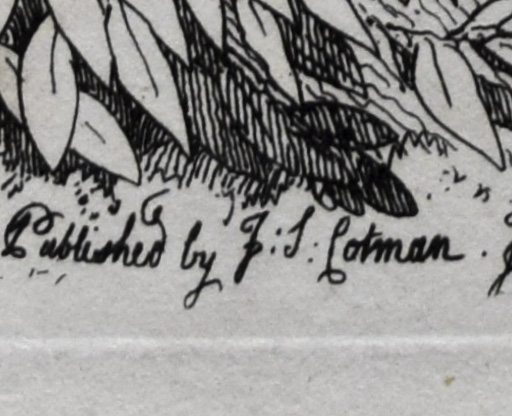

Inscribed on plate lower left, barely legible against the background detailing: ‘Etched and Published by J S Cotman/ Oct 3 [the 3 reversed] 1810’ and lower right, against the grass in script: ‘ Saint Marys Abby [sic] York’. Collection: Examples in various collections: e.g. National Galleries of Scotland, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford [WA1989.66.6]

Second Published state

As above but in some editions, with engraved script title ‘St Mary’s Abbey, York’ added lower centre and title inscribed by the artist in lower margin. d). The National Trust at Felbrigg, Norfolk has a large paper copy (?presentation proof). In addition some copies of the 1811 edition [as reproduced here] have a title inscription by the artist in graphite below the subject ‘St Mary’s Abbey/ Yorks’. This is called for in the printed description of subjects.

Third published state

As editioned by H G Bohn in ‘Specimens of Architectural Remains in various Counties in England, but especially in Norfolk. Etched by John Sell Cotman’, 1838, Vol. 2, series IV, vii. Printed more positively in black ink on sheet, 490 x 350 mm. The plate reworked with detail in originally blank areas and with clarification of the head of the seated figure. Additionally inscribed top centre of plate, ‘VII’. Cf. e.g. Norwich Castle Museum NWHCM : 1923.86.8