This is the twenty-third article in a catalogue of John Sell Cotman’s first series of etchings published in 1811. Here in plate 20 Cotman continues with his Yorkshire material, visiting one of the quieter of the county’s abbey sites.

Easby Abbey, Yorkshire, 1811

Private Collection

Photograph by Professor David Hill

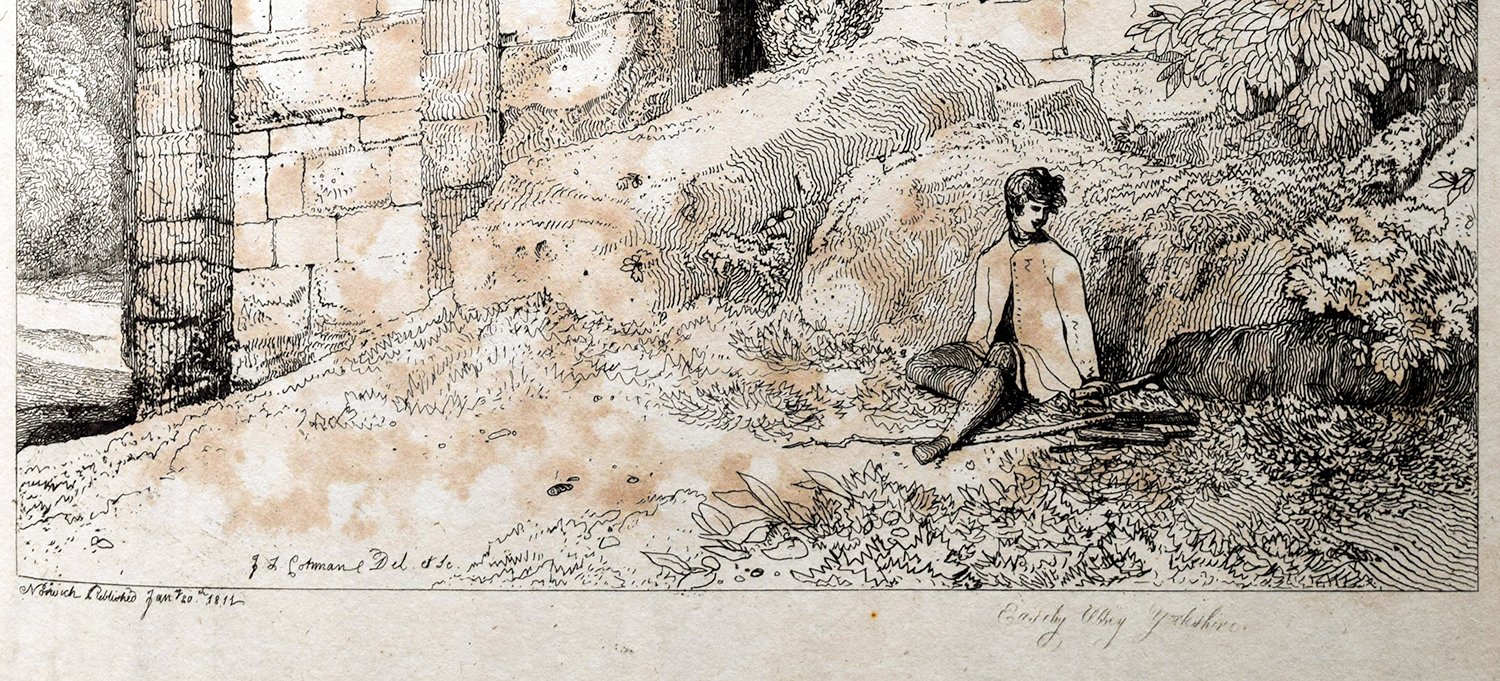

This is an upright architectural subject featuring an oblique view from the right of a range of three interlocking arches with a doorway below, terminating to the left with a three-stage tower crowned by a cluster of narrow gothic arches on slender columns. A solitary male figure sits on a bank in the right foreground.

The plate was etched by Cotman and dated 20 January 1811 for his first series of ‘Etchings by John Sell Cotman’. The series was issued to subscribers in parts, and the present subject was published as plate 20 in the complete edition of 1811. Plates 9 (Doorway at Kirkham Priory) and 11 (Rievaulx: interior of refectory) bear the same date, and together they form the 10th, 11th and 12th in the published order. The plate as originally published bears the title ‘Easeby Abbey, Yorkshire’ in a spidery and slightly shaky hand-engraved script. It is the largest plate that he had hitherto published, and the etching is crisp and delicate, but the sky seems to want more extensive work to soften the effect.

Right click on image to open full-size in a new tab. Close tab to return to this page.

St Agatha’s Abbey, Easby was founded about 1155 by the Constable of Richmond Castle, to house a community of White Canons. It enjoyed a favoured site in a wide sweep of the river, sheltered by Easby Banks behind. From the early fourteen century it enjoyed the patronage of successive generations of the powerful Scrope family of Bolton Castle in Wensleydale. At its peak it was an extensive complex, and despite the complete destruction of the abbey church, the ancillary buildings are extensive and substantial.

Cotman visited nearby Richmond in the company of Paul Sandby Munn, during their tour of Yorkshire in 1803. For a couple of weeks in early July they stayed with the Cholmeley family at Brandsby Hall near York, leaving on the 14th and arriving in Richmond the same day. On the 16th they were at Barnard Castle, so they perhaps spent the 15th sketching at Richmond and at St Agatha’s, a little over a mile down the river Swale.

Click on any image to open full-size in a gallery. Close gallery to return to this page

Easby Abbey, Yorkshire, 1811

Pencil on paper, 14 ½ x 10 ½ ins

York City Art Gallery, YORAG R316

Easby Abbey, Yorkshire, 1811

Private Collection

Photograph by Professor David Hill

No on-the-spot sketches of St Agatha’s by either artist are known today, and only two studio works by Cotman, the present etching and a pencil drawing at York City Art Gallery. The etching is the prime development of the composition. The York drawing is an artfully simplified version, typical of many hundreds of drawings that Cotman made for loan from portfolios of examples that he compiled for the use of students.

Both show the view of the Guests’ Solar as seen from the undercroft of the Guests’ Hall. Cotman found a perch slightly to the right from which to sketch.

The key element of his composition is the very fine range of interlocking arches that form two large windows. When Cotman visited almost nothing was known about the functions of different buildings at St Agatha’s, except for the church and cloisters. That knowledge had to wait for scholarly investigation in the later C19 and even modern research has numerous unresolved questions.

Even so, it would have been obvious that the windows let into a great hall designed for distinguished assembly and Cotman would no doubt have been able to recognise that the leftmost block served as the abbey’s reredorter, emptying into the stream below.

Given the extent of the remains, and the variety of subjects that the site offers, it seems obvious that Cotman must have sketched a number of subjects at St Agatha’s. We may wonder, then, quite why he selected this. Despite that lack of detailed archaeological information, there was a growing interest in the history and development of medieval architecture. Antiquarians up and down the land were visiting such sites and attempting to develop a sense of the origins, chronology and dissemination of architectural styles and motifs. Cotman’s home county was particularly fertile ground for such work, and the artist already enjoyed the patronage of one of Britain’s leading antiquarians, Dawson Turner of Yarmouth. Turner had already bought several of Cotman’s watercolours of architectural subjects, including a large watercolour of Fountains Abbey (see plate 19), and Cotman engaged keenly with his patron’s knowledge and interests.

This is perhaps the first subject amongst Cotman’s first series of etchings to indicate an academic interest in antiquarian history. The composition selects out the window as of implicit significance in itself. It had already been recognised that the way in which interlocked round-headed Romanesque arches produced pointed Gothic arches, was indicative of a transition from one architectural era to the other. Cotman could see examples of the former all around in Norfolk, Norwich Cathedral has ranges of them, as does Castle Acre Priory,

The particularity of this window at St Agatha’s lies in the way in which its main arches are not round but shallow-pointed. This would place them exactly on the cusp between the Romanesque and the Gothic, and make them a key reference in charting the chronology of that stylistic shift. Cotman appears intend his plate to contribute to the developing knowledge of architectural history. At just about the point that this subject was published, he elected to thrown in his lot with the Dawson Turner family and take up duty as their private tutor and draftsman. Seeking out architectural subjects for etching would occupy him almost exclusively for the next ten years.

Besides antiquarianism, the image also projects something of the spirit of an archaeologist. Cotman appears to record every stone. This is more apparent than real, for whilst he captures the character of the blocks, that is through re-imagination rather than exact delineation. Nonetheless, he does replicate the proportion and varied shape of the ashlar. No two pieces are the same, ranging from large to small, and through thin slabs to rectangular and square. It appears that he has considered and registered every single block. He notes with equal care the form of the bases, columns and capitals, besides the three blind quatrefoils with floral detail on the points, and each individual stone that makes up the ribs of the arches. He even notices a blank in each of the blind arches, presumably where a piece of the facing is missing.

Comparison of the etching with the surviving structure reveals numerous differences. It is plain, for example that the structure was in better condition in Cotman’s time. Since then large sections of the ashlar has been lost, an opening has appeared below the windows, and a large section of the left corner has disappeared. The blank in the left blind arch is present, albeit in a slightly different position, but the right blank has disappeared. It is not clear whether it ever existed, or whether it has been made good, but in the light of the more general depredation the former seems unlikely.

Perhaps the most interesting difference is in the drawing of the voussoirs [the individual stones from which the arch ribs are built]. Cotman’s drawing of the joints between them is seriously out of perspective in places. A camera records them correctly as a matter of course. The problem becomes plain when one compares the stones of the left arch with the equivalent stones in the window next to it. They should be almost identical. Cotman has perhaps been thrown by the complex moulding of arches with a deep trough carved into each rib. The fact that he felt the need to engage at all with such detail suggests that his specificity was meant to carry aesthetic purpose. It is as if he is positively inviting us to consider the shaping and fitting together of the stones, and the systematic sophistication and refinement of such processes.

As is commonly the case, Cotman introduces a figure into his composition. In this case he gives us a young man apparently in his late teens or early twenties, wearing his hair fashionably tousled. He is dressed in a collarless jacket and breeches. The jacket is perhaps somewhat old-fashioned. The favoured style of Cotman’s gentlemen contemporaries was for coats and jackets cut away at the front, to show off the breeches. This buttons right down the front, is possibly made of leather, and even if woollen cloth would at best have been considered practical wear. It would have proved useful, if intending to be out for any length of time.

We know that in 1803 Cotman visited St Agatha’s in the company of fellow-artist Paul Sandby Munn. It seems unlikely that Munn supplied the subject for he was several years older than Cotman’s twenty years, and by the report of their Yorkshire host, Mrs Teresa Cholmeley of Brandsby Hall, might easily have been taken for forty. This figure is certainly much more of Cotman’s own age, and might well be a self-portrait.

In any case the figure represents the act of visiting such a place as a significant activity for a young man. Furthermore, the visit takes place in simple circumstances. The young man sits directly on the ground, with only a bank behind for comfort. He has little in the way of equipment. An untrimmed hazel wand lies at his feet, and his attention is focused on the ground beside him, where he appears to unscroll something, perhaps a map?

Such figures are a particular feature of Cotman’s work at this time and occur at intervals throughout the remainder of his career. Cotman’s figures would reward extended investigation. Certainly young men variously sitting or lying on the ground occur in particular profusion in his work between about 1809 and 1811. Sometimes there might be some specific activity being undertaken, such as sketching but more often the main statement is of a simply rustic contentment of being in direct contact with the ground. There are young men in all manner of attitudes. Some recline and even positively luxuriate on the grass, some even sleep. It is perhaps proof of their importance to him at this stage of his career that the previous plate in the series offers such a close parallel as to suggest to the viewer a theme. This figure, however, projects a different impression to that at Fountains. Here the figure is remarkably straight-backed and poised. Being contentedly grounded, Cotman seems to argue, is also an appropriate condition for a person of bearing.

Summary of known states:

First published state

As editioned by Cotman for ‘Etchings by John Sell Cotman’, 1811, where plate 20.

Line etching, printed in black ink on soft, heavyweight, off –white, handmade rag wove paper, image within key-line approx. 345 x 251 mm on plate 370 x 262 mm) on sheet 474 x 340 mm.

Inscribed in plate, lower left centre, inside margin line) ‘J S Cotman Del et Sc’, and below the margin line, lower left: ‘Norwich. Published Jan y 20th 1811’. Also inscribed to the right below the margin line, in a rather faint script ‘Easeby [sic] Abbey Yorkshire’.

Collection: Examples in various collections, e.g. Norwich Castle Museum NWHCM : 1956.254.22

Second published state

As editioned by H G Bohn in ‘Specimens of Architectural Remains in various Counties in England, but especially in Norfolk. Etched by John Sell Cotman’, 1838, Vol. 2, series 4, vi.

Line etching, printed in black ink on soft, heavyweight, off –white, handmade rag wove paperimage within key-line approx. 345 x 251 mm on plate 370 x 262 mm on sheet of ?machine-made heavyweight wove paper, 493 x 353 mm

Plate as 1811 edition except for the addition of inscribed numeral ‘VI’ top centre.

Examples in numerous collections, e.g. Norwich Castle Museum, NWHCM : 1923.86.22

References:

Popham, 1922, no.22.