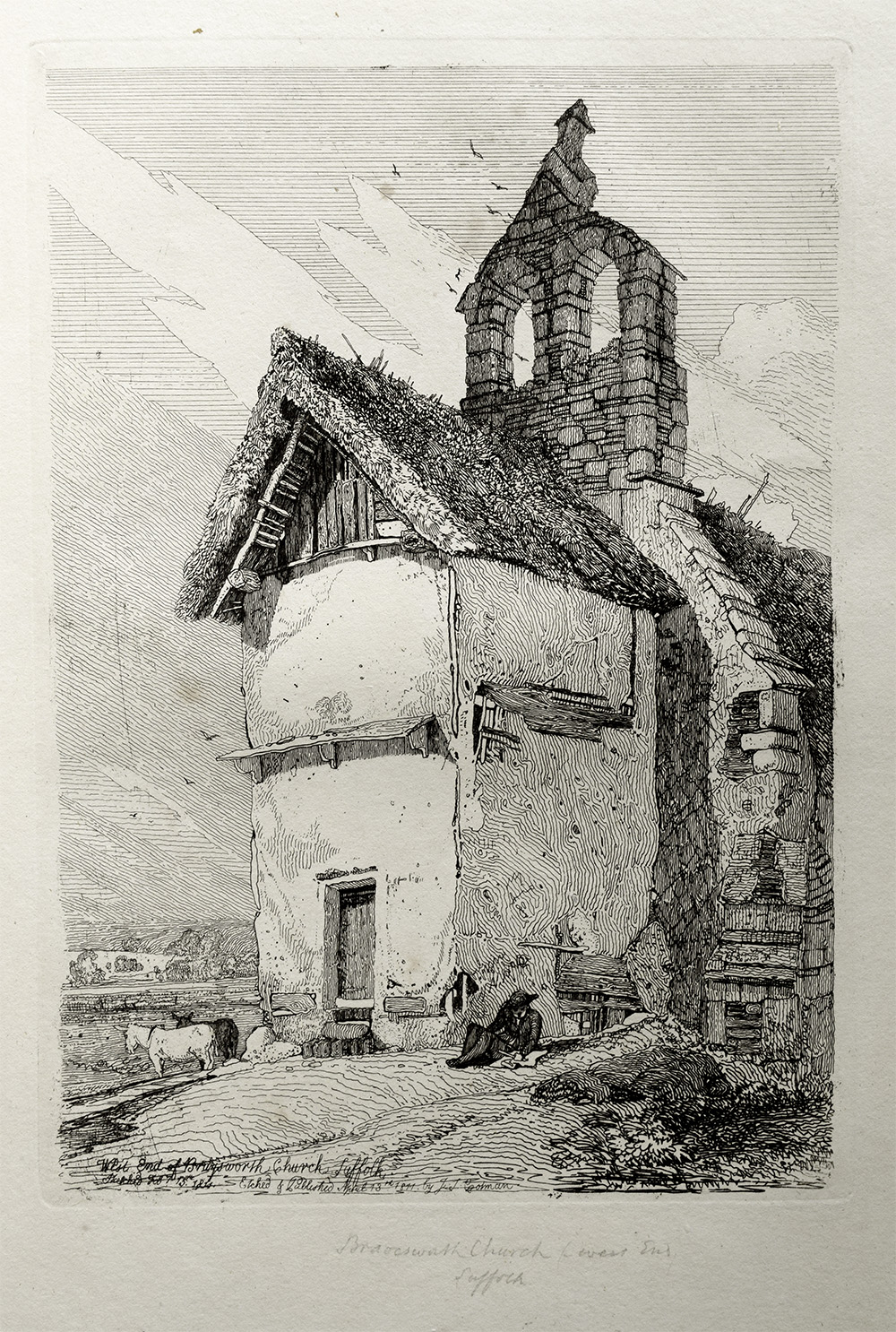

This is the twenty-fourth article in a catalogue of John Sell Cotman’s first series of etchings published in 1811. Here in plate 21 Cotman gives us a third subject at one of the most obscure sites of the series.

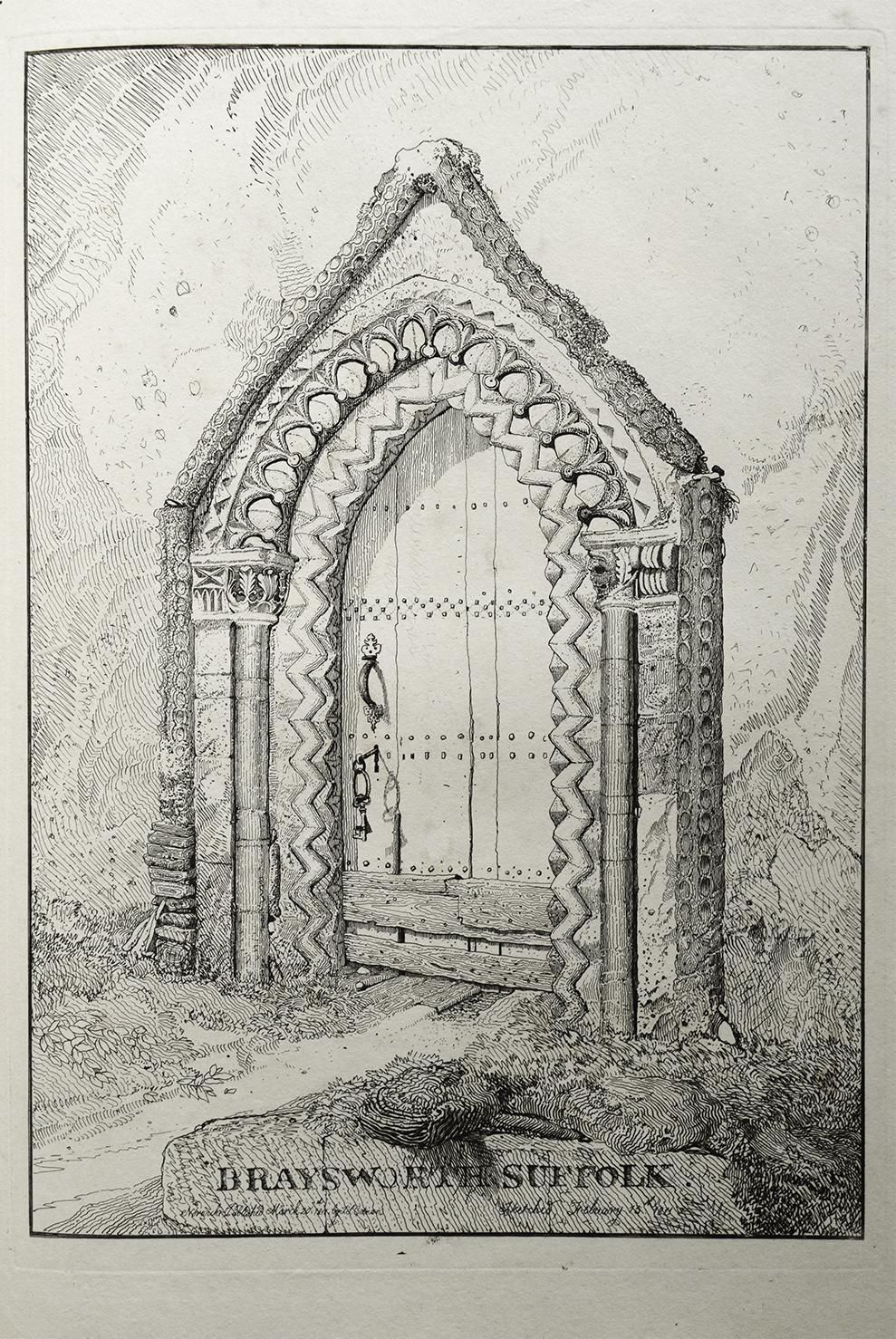

North portal of Brayesworth Church, Suffolk, 1811

Private collection

Photograph: Professor David Hill

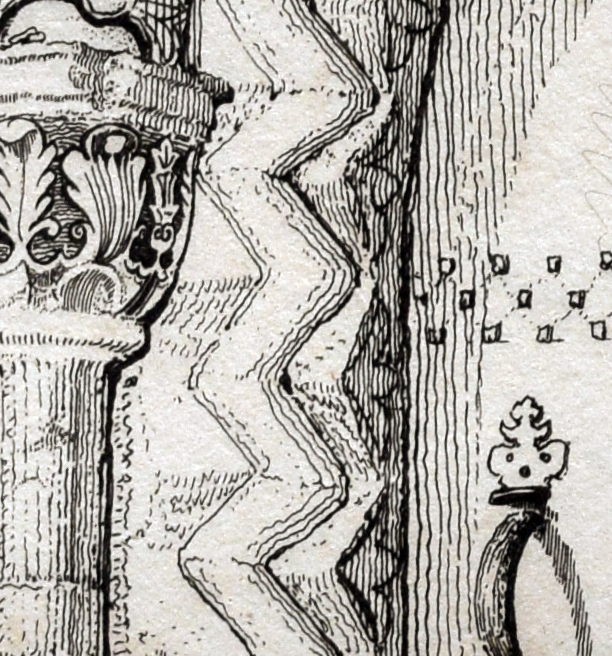

This is a copper-plate etching of an ornate Norman portal consisting of a battered wooden door, framed by a broad double-chevron moulding and flanked by a slender column and impost either side. Each capital is differently carved and the whole is surmounted by a main arch of globes wrapped in acanthus wreaths, surrounded by sawtooth moulding. The portal is framed by a scalloped moulding which rises to a triangular pediment. The subject is identified in a title on a foreground stone: ‘BRAYSWORTH SUFFOLK’. Beneath that Cotman has inscribed in a slightly shaky script: (left) ‘Norwich Published March 29th 1811 by J.S.Cotman’ and (right) Sketched February [sic] 15th 1811

The plate was etched by Cotman for his first series of ‘Etchings by John Sell Cotman’. This was issued to subscribers in parts, and the present subject formed plate 21 in the complete edition as published in 1811. It is the sixteenth plate of the series in date order, and the first of three Braiseworth subjects to be etched, although in the final order for some reason Cotman gave it last (see plates 12 and 14). Apart from the previous plate of Easby Abbey (plate 20) it is the largest that he had yet attempted, and the etched line is crisp and clear.

Right click on image to select open in a new window. Close window to return to this page.

Cotman gives the place-name as ‘Brayesworth’ or here as ‘Braysworth’. The current orthography is ‘Braiseworth’. The title inscription identifies a sketching visit to the site on 15 February 1811. Braiseworth is 30 miles or so south of Norwich, a little way east of the Ipswich road. It would have been a long day’s excursion from Norwich, so this was no idle undertaking. It was also the middle of winter, so even if pleasant, certainly not balmy. It is a fairly remarkable excursion if made from Norwich specially, but even as part of a trip to a more distant destination, it seems a questionable diversion. The obscurity is rendered all the more wilful by the fact the site provoked three plates..

Click on any image to open full-size in gallery view. Close gallery to return to main page.

Right click on image to select open in a new window. Close window to return to this page.

The Norman church that Cotman visited was replaced in 1857 by a new one a few hundred yards away. The Norman decorative features were dismantled and re-erected as part of the new structure.

Cotman’s portal is to the left.

Please note, this building is now a private house.

Image feed from Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture

The present portal was reused as the entrance inside the porch. The ensemble survives today, but the church was deconsecrated in the 1970s and sold off as a private house. The Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture website gives the history and a description and Simon Knott gives a personal account on his excellent Suffolk Churches website.

North Door of Old Braiseworth Church, Suffolk, 1811

Graphite on paper, 270 x 190 mm

Bradford Museums and Art Galleries (1925-022)

The etching was based on a pencil drawing at Bradford Art Galleries and Museums. The etching follows it closely, except for introduction of shadows to the door handle and keys. The detail in the drawing is carefully crafted, to the extent that the right-hand capital, now eroded beyond interpretation, can be seen to depict a green man – a human face surrounded by garlands of leaves. Cotman’s observation in the drawing even extends to the herringbone pattern in the spandrel above the portal. This can be recognised today, but was omitted from the etching.

The Braiseworth portals are significant examples of their genre and Cotman was proud to advertise that he had found them. Not long afterwards he wrote to his Yorkshire friend and patron Francis Cholmeley at Brandsby Hall to tell him of his discovery. [Cholmeley archive, North Yorkshire CRO, Northallerton, ZQG, transcribed and reproduced by Mike Ashcroft and Adele Holcomb, Cotman in the Cholmeley Archive, NYCRO, pp. 42-43] .

The letter contains a drawing of the particulars. Cotman even gives a detail of the first order of decoration: ‘The Ornament enlarged’ and comments ‘& not totally unlike Kirkham doorway’.

The Kirkham doorway is that given in Plate 9, but any specific connection is distant at best. Nonetheless there is some significance in the fact that Cotman speculates on the connection at all. He is affecting a degree of antiquarian expertise. The comment, choice of subject, and late decision to include three plates into an already well-advanced series suggests that the visit to Braiseworth had made up his mind to devote himself increasingly to antiquarian work. As it turned out it was to occupy him almost exclusively for the next decade.

Click on any image to open full-size in gallery view. Close gallery to return to main page.

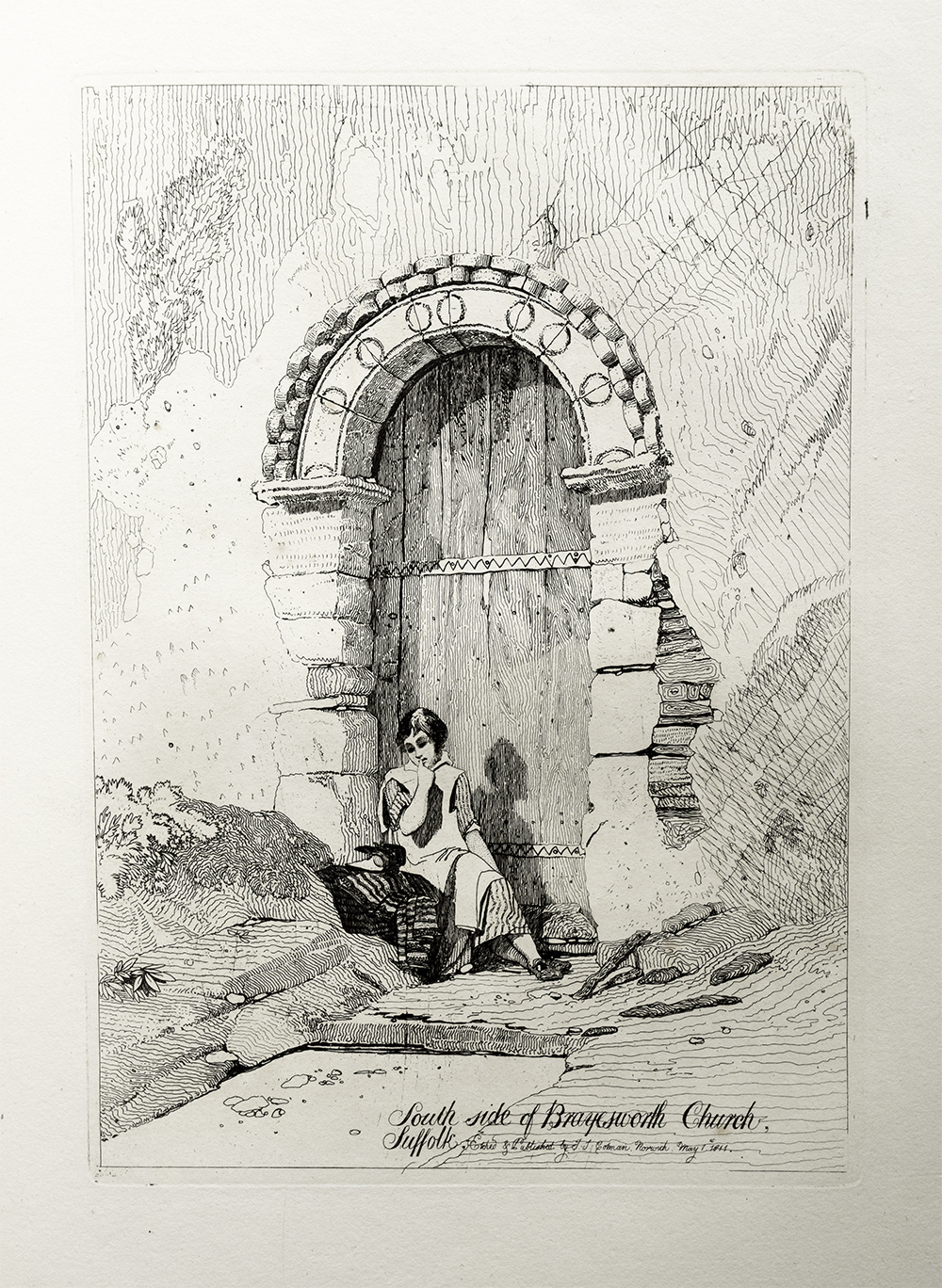

North Door Braysworth Church Suffolk, 1827

Trustees of the British Museum (1870,0514.1540)

Depictions of Braiseworth Old Church appear to be rare. Apart from Cotman’s etchings the only other treatment that readily presents itself is an etching of the north door by Henry Davy. This was published in 1827 in Davey’s Antiquities of Suffolk. Davy had been trained by Cotman, and worked as his assistant until at least 1818 when he began to work independently. He modelled himself directly on his master, and the plate might easily be confused with Cotman’s.

The rarity of records of the original church makes the two artists’ work accuracy a matter of some importance. The portal as it now stands has been dismantled, moved, cleaned up and rebuilt. One obvious feature of its current condition is that it has been pointed with a rather obvious dark grey mortar. This accentuates the divisions between blocks rather more than the continuity of pattern. It is also possible that some blocks were replaced or recut. It is also possible that the component blocks blocks were not reassembled perfectly in their exact original order.

Comparing an etching to a photograph is not as straightforward as we might wish. Notwithstanding the fact that it is no longer possible to view the portal from the same angle, since it is now housed in a porch, the etching in any case represents understanding rather than mere projection. Cotman’s treatment of the main order of carving, with the spheres clasped by palmette foliage both above and below, gives a more fully rounded idea than can be photographed. A second photograph on the CSRBI website taken from below adds another dimension to the frontal photograph.

Click on any image to open full-size in gallery view. Close gallery to return to main page.

Cotman also attempts to give a fuller story of the outer frame, with its twin rows of scallops, which can only be seen partially from any one angle. To the left of the door in the etching it is shows a cogwheel edge, but to the right he conflates together views from left and right to give a rather more complete account of its form than can actually be seen from any one viewpoint.

Click on any image to open full-size in gallery view. Close gallery to return to main page.

There are some elements, however, which Cotman does not seem to properly capture. The main chevron, for example, whilst curved in profile as Cotman suggests, is actually much crisper in outline. Cotman gives it a rather soft character, whereas its edges and points are sharp. The same is true of the triangular shapes inside the chevron, whose ridges are keenly defined, whereas Cotman’s etching softens them.

Click on any image to open full-size in gallery view. Close gallery to return to main page.

It might have been possible to imagine that the edges were indeed softer when Cotman drew them. Portals were routinely lime-washed, allowing a considerable build up over the centuries. However, Davy’s plate also records the portal before it was moved and rebuilt, and his edges are clear-cut as we see them today. Davy’s plate is such an exact revisit to Cotman’s subject, that it seems plain that he intended it to be seen as corrective of his erstwhile master’s errors. He had the great advantage, or course, of Cotman’s etching to compare with the original. That said, Davy’s proportions differ from Cotman’s, the former being slightly etiolated, the latter a little compressed.

Click on any image to open full-size in gallery view. Close gallery to return to main page.

There is one especially puzzling difference in detail. If we look at the keystone of the chevron doorframe, we can see that it differs very little between between Cotman’s pencil drawing and etching, but more significantly with Davy’s etching which in turn corresponds fairly closely to the surviving structure.

Cotman was possibly not yet quite the complete master of architectural record-taking, nor of the history of decorative motifs. Cotman’s instinct, however, had long cautioned him against antiquarian mechanicality, and he must have been well aware of the pedantry that he would be judged by in this area. Years earlier, when at Peterborough he had excused himself from the effort of drawing the cathedral by saying; ‘it is too perfect for my pencil, every architect can make a better drawing from that than I can, therefore to them I will yield up my claims.’ [Letter to Dawson Turner, 9 August 1804, Norfolk Museums Service, quoted Cotman in the North, 2005, p.77] He was well enough aware of the virtues of good observation and understanding, but he felt that the discipline and mind-set required of the architect might dim his artistic lights. Some architectural subjects did suit his pencil, and in the same letter to Dawson Turner he reports being fired up by Crowland and Howden, both of which remain to be considered in the present series. His greatest excitement, that time he reports with wry self-knowledge, was in finding some particular forms of leaves.

This plate offers ample evidence that his drawing interests still veered towards the incidental. Some of his most patient attention is bestowed on the doornails. It seems as if he has scrutinised and individualised every one. As usual he traces each contour of the wood grain, and personalises every timber, even those mouldering underfoot in the threshold. Also, as is customary, he finds poetry in latches and locks.

The keys dangle in the lock and the latch awaits pressing. Each is brought delicately into relief by shadows. Once again Cotman turns a potentially dry subject into a meditation on opening and entry. What lies on the other side of any doorway? What might be left behind on the outside? It is not hard to sense a dilemma in himself. He was about to enter a commitment that would frame everything that he touched. Here, right across the surface, every pop and whistle, line and squiggle, rebels against being tied down to mere delineation; every touch wants to take on a life of its own.

Summary of known states:

First published state

As editioned by Cotman for ‘Etchings by John Sell Cotman’, 1811, where plate 21.

Line etching, image within thick key line 352 x 249 mm (13 5/8 x 9 7/8 ins) on plate 367 x 262 mm (14 3/8 x 10 1/4 ins) printed in black ink on soft, heavyweight, off white, hand-made rag wove paper, 474 x 340 mm

on plate bottom centre of subject ”BRAYSWORTH SUFFOLK”; on plate bottom left centre of subject ”Norwich Published March 20th 1811 by J.S. Cotman”; on plate bottom right centre of subject ”Sketched Febuary [sic] 15th 1811′

Collection: Examples in various collections, e.g. Norwich Castle Museum NWHCM : 1956.254.23

Second published state

Line etching, image within thick key line 352 x 249 mm (13 5/8 x 9 7/8 ins) on plate 367 x 262 mm (14 3/8 x 10 1/4 ins) printed in black ink on heavyweight ?machine-made wove paper, 493 x 353 mm

As editioned by H G Bohn in ‘Specimens of Architectural Remains in various Counties in England, but especially in Norfolk. Etched by John Sell Cotman’, 1838, Vol. 2, series 4, xvii. Plate unchanged from 1811 edition except for addition of numeral inscribed ‘XVII’ top centre of plate margin.

Examples in numerous collections, e.g. Norwich Castle Museum, NWHCM : 1923.86.23

References:

Popham, 1922, no.23.