This is the twenty-fifth article in a catalogue of John Sell Cotman’s first series of etchings published in 1811. In plate 22 Cotman tackles one of the most important subjects of his early career. Here we begin by introducing the subject.

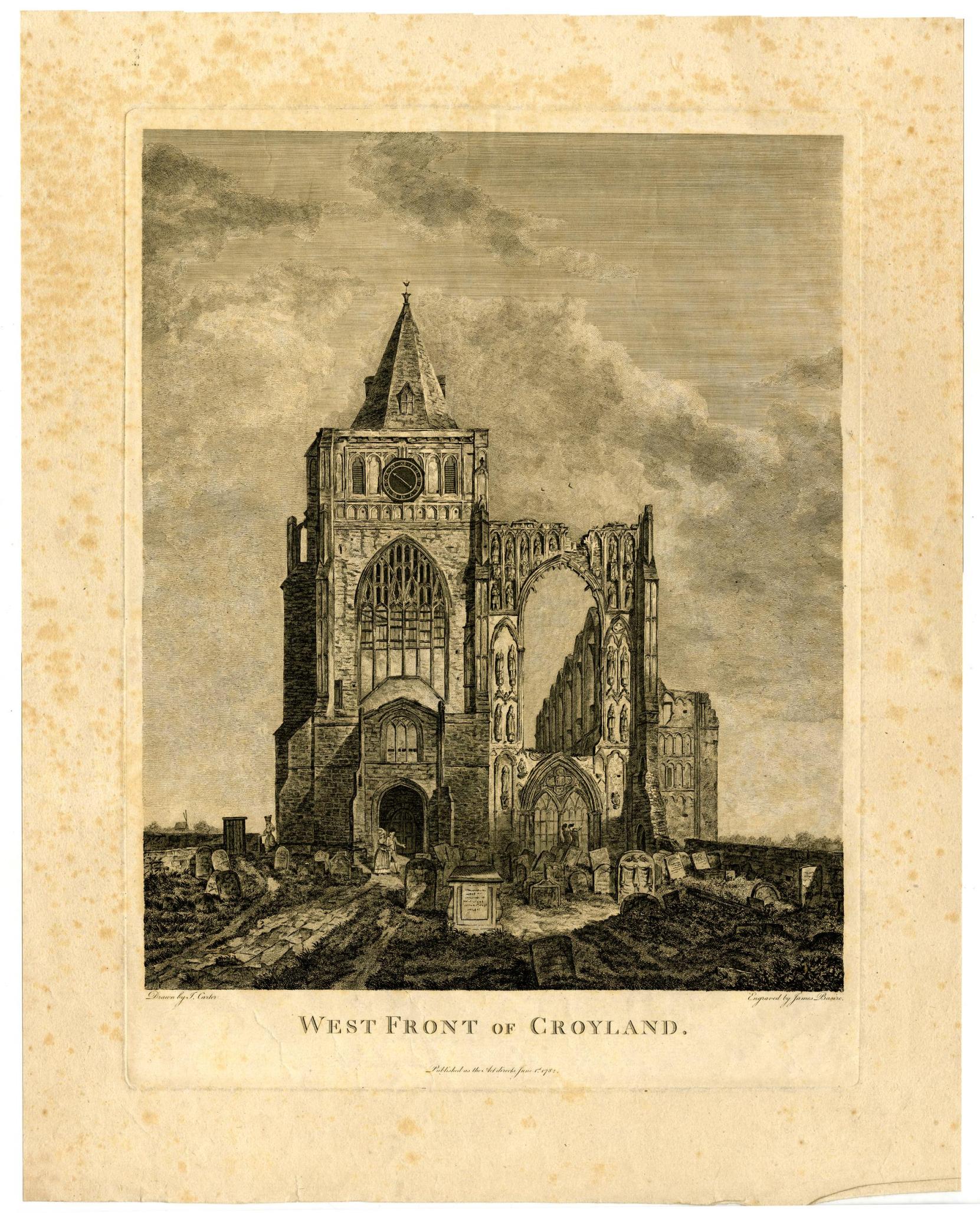

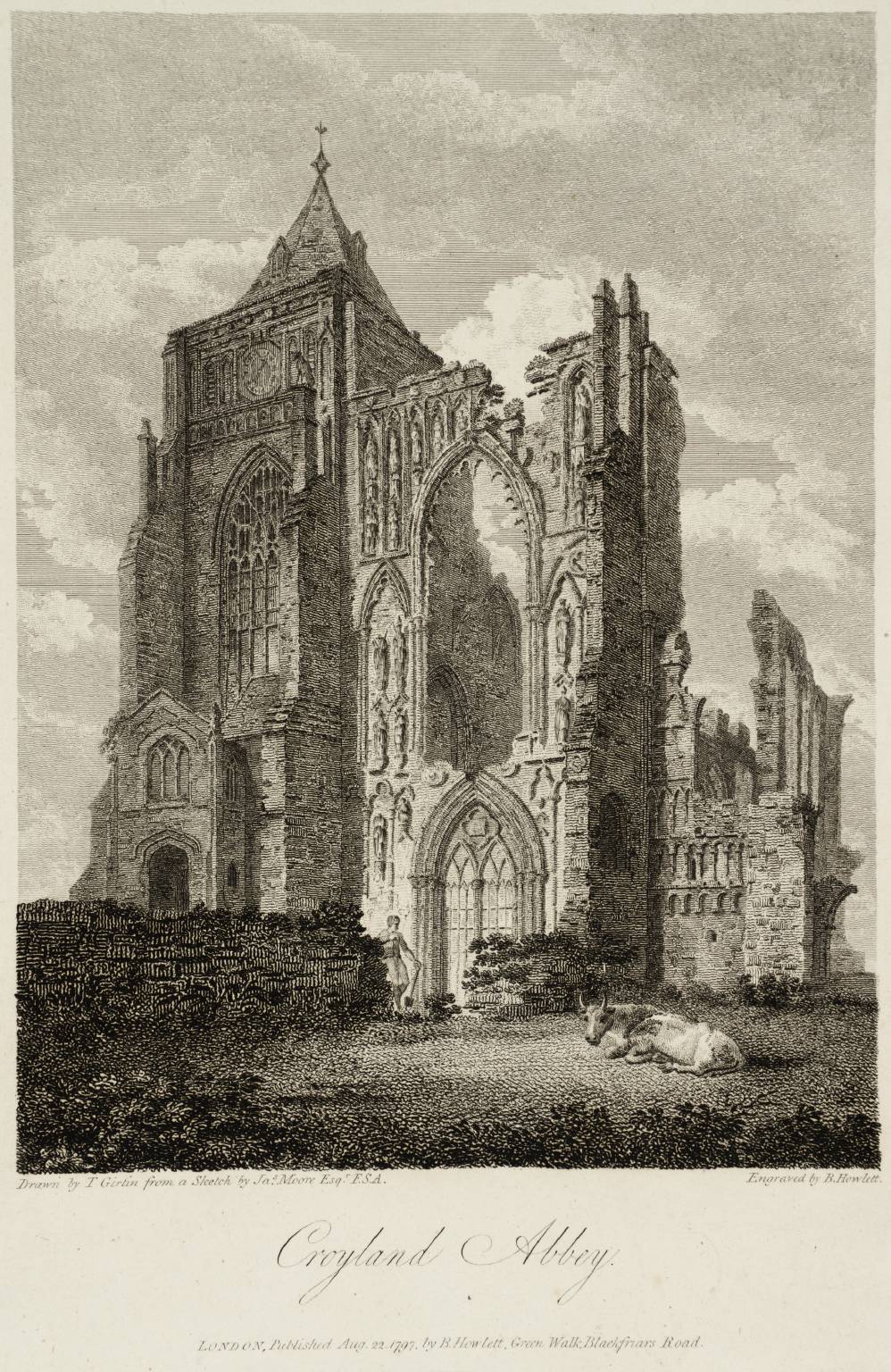

Croyland Abbey, Lincolnshire, 1811

Private collection

Photograph: Professor David Hill

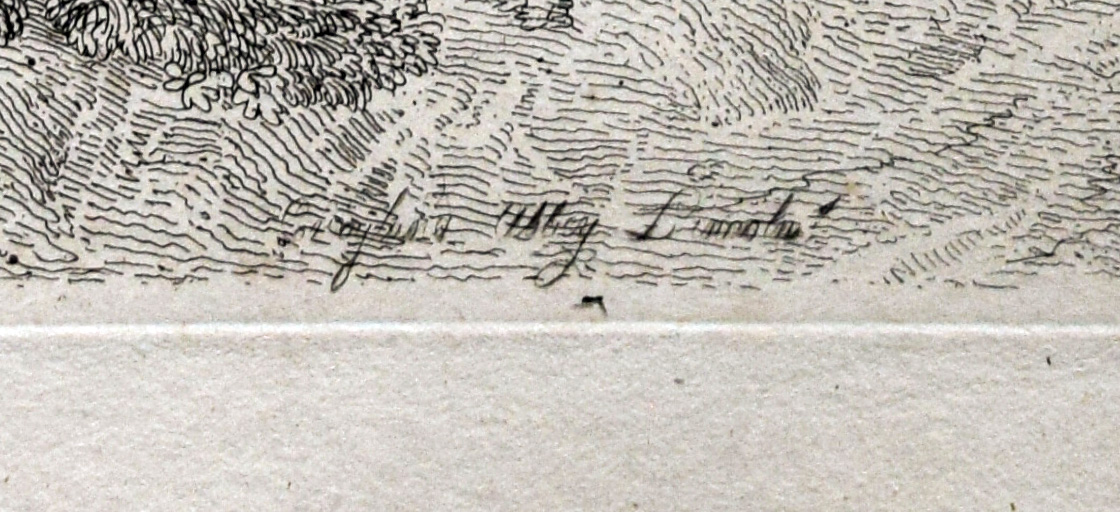

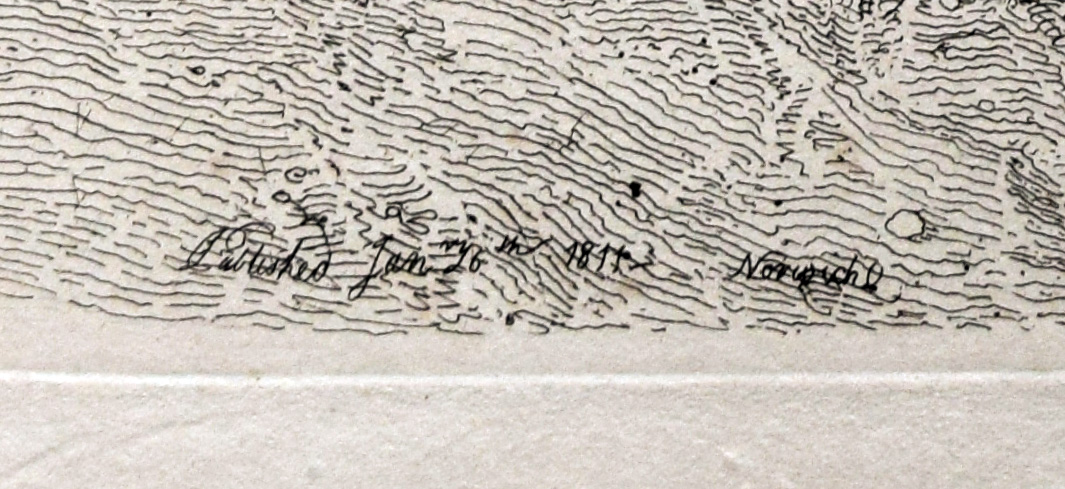

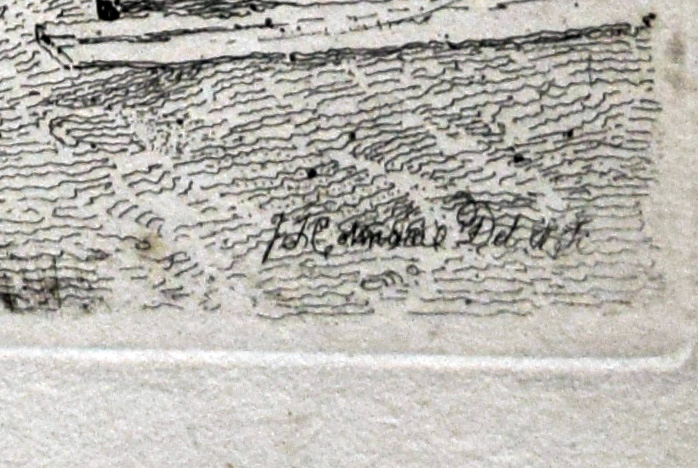

This is an upright composition of the remains of the west front of a grand medieval church. To the left is a bulky tower with a two-storey entrance porch, and great traceried window flanked by buttresses, supporting a large square belfry with a clock in its face. The whole is surmounted by a squat octagonal spire, with four small dormers facing the cardinal points. To the right is the west front to a nave, with a large west window, bereft of its tracery, and set above a large gothic portal with twin doors. The face is decorated five tiers of statues in niches. The subject is identified in a title scratched against the grass lower centre: ‘Croyland Abbey, Lincolnshire’. To each side of that Cotman has inscribed in an equally shaky, but more legible, script: (left) ‘Published Jan 26th 1811 Norwich’ and (right) ‘J.S.Cotman Del & Fc’.

The plate was etched by Cotman for his first series of ‘Etchings by John Sell Cotman’. This was issued to subscribers in parts, and the present subject formed plate 22 in the complete edition as published in 1811. It is the thirteenth plate of the series in date order. In January 1811 Cotman appears to have been finding his full confidence in etching. This is the largest plate in the series, and is dated 26 January, less than a week after the previous largest Easby Abbey (plate 20) which is only very slightly smaller.

Right click on image to open full-size in a new tab. Close tab to return to this page.

Crowland Abbey is about eight miles north-east of Peterborough. The spelling is somewhat confusing. The abbey has long been given as Croyland, whilst the village as Crowland. Cotman calls the abbey Croyland and that spelling persisted at least until the 1999 edition of the official guidebook but since then the church has aligned its spelling with the village.

Photograph by Professor David Hill, 11 December 2005.

The abbey is one of the Fens’ most deep-rooted historical sites. Historic England gives a detailed listing and the church has its own website. Briefly, a Mercian monk named Guthlac retreated to a remote island here in 699 and set up a simple hermitage and oratory. H was beset by demons speaking in the ancient British tongue, but banished them and enjoyed a parlous existence until his death in 714. Two years later King AEthelbald founded a monastery in the hermit’s honour. This prospered until it was sacked by Danes in 870. A second abbey was begun in 946 and prospered until a fire of 1091. Some rebuilding was attempted but this was swept away by a new abbey begun in 1113. This collapsed in an earthquake in 1118 and setbacks and new builds alternated at intervals for the next four centuries. The west front was rebuilt about 1275, and then remodelled in the mid-1400s with a much larger window surrounded by tiers of sculpture. The sculpture has been studied in detail by Professor Jenny Alexander of the University of Warwick [Alexander 2014 and see other works listed in Part#3, References]. The abbey was dissolved in 1539 and whilst the majority of the church and abbey buildings were dismantled, the North West tower and north aisle survived, retained for use as the parish church.

Photograph by Professor David Hill, 11 December 2005.

Cotman’s subject is the west end of the church seen from a close viewpoint in line with the former south aisle. His composition is dominated by the two great west windows and the portal, together with the five tiers of statues on the west front. Cotman spent three days at Crowland 18-20 August 1804 and penned an account of his experiences to his Yarmouth patron Dawson Turner:

Croyland is most delicious, you know how I esteemed my Howden [seen in 1803, see plate 23]. This Oh this is far, far superior. Castle Acre [which he had enthused about in his previous letter, nine days earlier] to it is as nothing. – I am sorry I am obliged to paint this in so brilliant a manner as it precludes all hopes of my ever seeing it now with you, & yet I feel my pen incapable of describing it ‘tis so mangificent, ‘tis most Magnificent – The old part is full of sketches – the Door, the Window in short, the whole. Wonderful – there is not one upright line in the composition therefore let not the Botanists [Dawson Turner was distinguished in that field] criticise when they come to see it if[?] they find me out of the perpendicular –..

The Inn is now quite full & nothing is heard but “Hounds & Horns, Horns & Hounds, Hounds & Horns”. You cannot imagine my disagreeable situation in a paltry Inn full of the worst Company I ever heard. Hounds & Horns then Song & a Villain of a fellow commanding silence with oaths too dreadful to be repeated & this I find is their common custom from Morn ‘till Night – I hope these brutes will let me sketch tomorrow I doubt if much, farewell Sir for to stand this noise longer would drive me mad – This continued sound of noise & havock is really disgraceful to Man -–The noise of Brutes is music to it – Oh! For a Welch Harp. – or to be looking at some of your La Cave Sketches [of donkeys and cattle, much admired by Cotman] – I really am unwell — & to go to rest is impossible – pity – me – pity me even though I am at Croyland, farewell – There is now a cry of Murder – & take the poker & a thousand other noises, – & even amidst it all in another Room Singing. – My Landlord at Peterbro’ said they were a set of shocking Villains –

Sunday Evng – I have now finished all that I suppose I shall be able to finish (the Western Front) during my Sketching it, I was so molested that I am sorry to say I was obliged to give one of the ringleaders a sound flogging. This brought on the storm with increased fury ‘til at last I was obliged to yield & here I am in the middle of the Day almost afraid to stir lest I again encounter this villanous Rabble tomorrow I certainly shall quit this place & I hope with my Head on –..

Peterborough (Tuesday) As I suspected, they would not let me alone. I left Croyland last night partly on account of their ill treatment & partly on my own pleasure, for I have by some how or other finished three Sketches which are quite sufficient to give a good representation of the place I wish I could show you them

Dr Sir your obliged St

John S Cotman

Cotman speaks of Crowland as a revelation, and presents it to Dawson Turner as a great discovery. Cotman’s patron eventually became a celebrated antiquarian but at this time his speciality was botany. He published Synopsis of British Fuci in 1802, Muscologia Hibernicae Spicilegium (Irish Moss Ferns) in 1804 and Botanist’s Guide through England and Wales in 1805. It would appear that his later passion was just awakening, and somewhat under Cotman’s encouragement. Cotman does appear to have been a little wary, however, that the scientific mindset might militate against the artistic, but nonetheless hoped that his work would be admired.

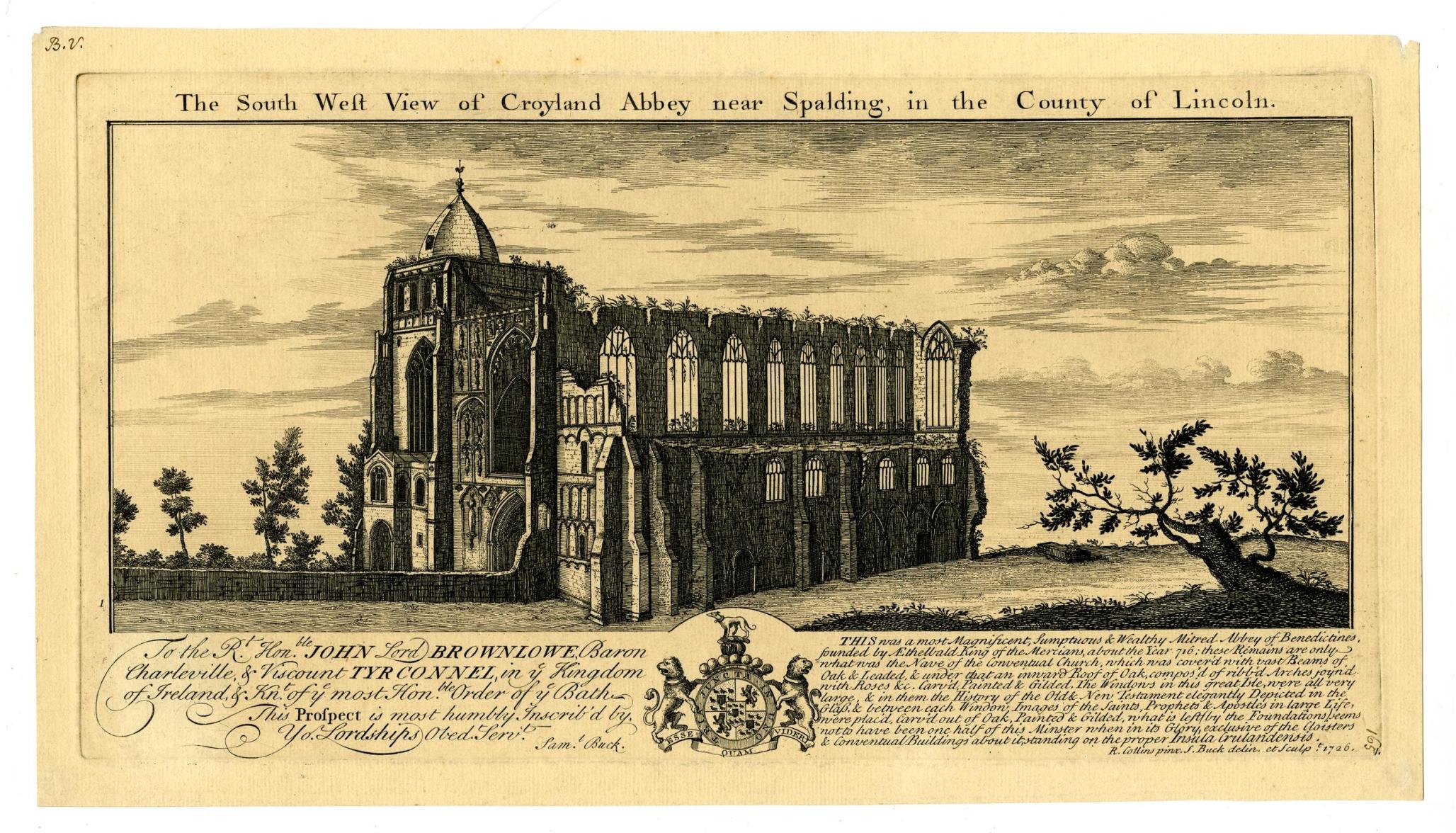

Despite Cotman’s proclamation, Crowland was by no means terra incognita. It had been recorded by numerous artists before him. There were engravings, for example by Samuel Buck from 1726, James Basire 1782, William Williams of Norwich from the later 1700s and (perhaps a surprising oversight) that engraved by Bartholomew Howlett in 1797, after Cotman’s great influence Thomas Girtin. Drawings circulated amongst connoisseurs: The British Museum has a drawing by Frederick Ponsonby and the British Library has studies of the sculptures on the west front by William Stukeley drawn in 1726 [reproduced in Alexander 2014]. By the later eighteenth century Croyland appears to have been well established as a subject. Girtin painted it in a watercolour at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, which was engraved in 1797 by B. Howlett. Girtin based his watercolour on a 1789 drawing by the antiquarian James Moore, but as Greg Smith, author of the recently published online catalogue of the works of Thomas Girtin, has kindly pointed out (see comments below) does not seem to have visited the abbey himself. Turner visited in 1794, and sketched the west front from a similar, but more oblique, angle to Cotman.

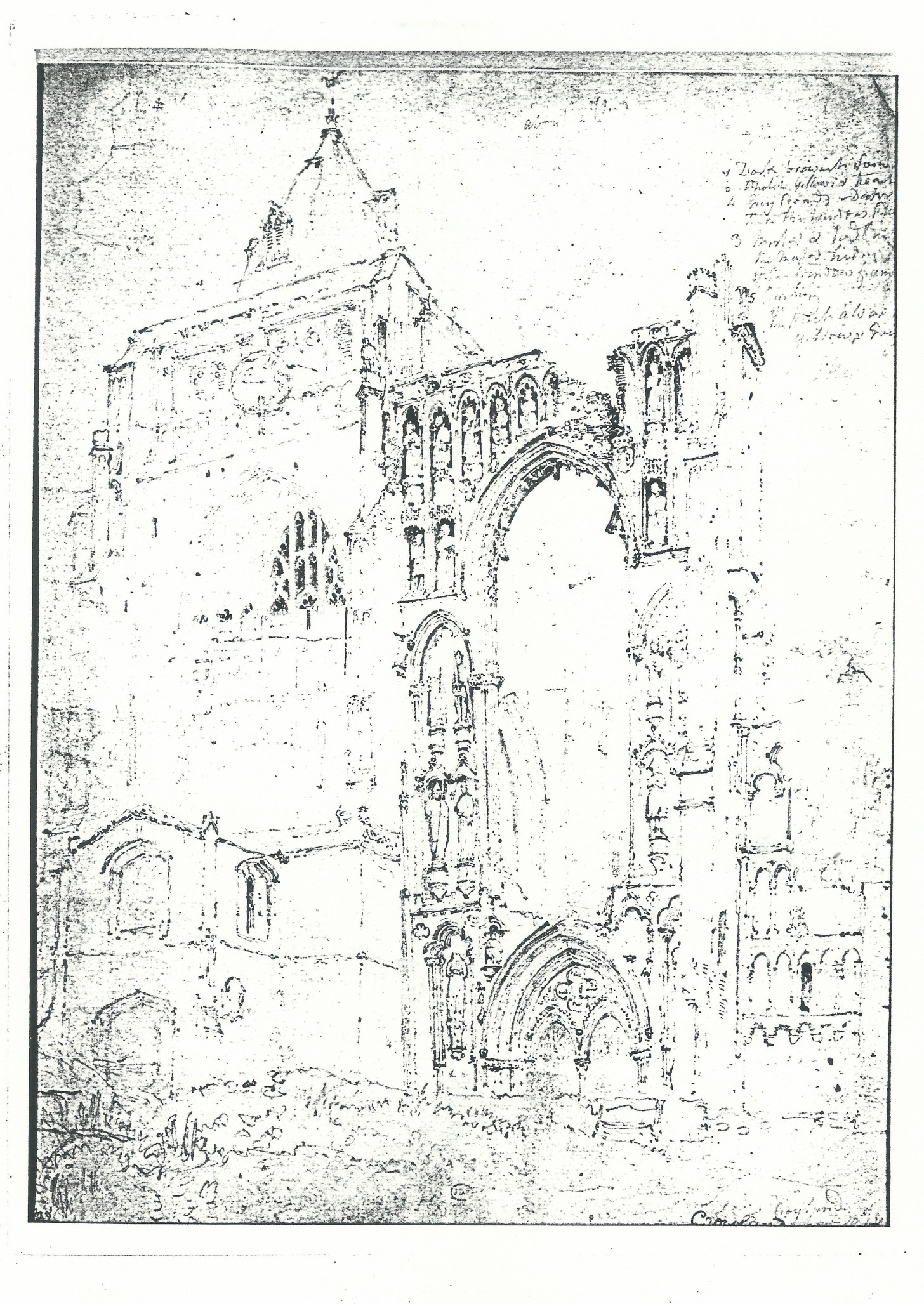

Cotman’s letter tells us that he encountered similar company at Crowland to St. Guthlac yet managed three on-the-spot sketches despite his molestation. At the point of first posting this, I was unaware of any of these, but within an hour, the artist and Cotman scholar Jeremy Yates alerted me to the following drawing at the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery in Swansea. The photocopied image that he sent me, despite the degradation in quality, does contain lots of extremely useful information, and is certainly worth showing here until a replacement can be obtained.

The west front of Crowland Abbey, Lincolnshire, 1804

Graphite on paper, 13 3/8 x 10 ins, 340 x 254 mm

Inscribed with date -? 20 Aug, lower right

Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, Swansea (80.1947)

From an old photocopy courtesy of Jeremy Yates

The drawing records exactly the same material as the etching. The details are too fragmented in the reproduction to discuss with any confidence, but one feature of the drawing does warrant comment. At the top right are some quite detailed colour notes. These key to numbers 1 to 5 scattered across the subject. It will be good to see where those numbers occur when we have an image with better resolution, and to transcribe the notes fully when the opportunity arises. Such notes are common in Cotman’s sketches of this period, and they would certainly reward collation and consideration. Cotman was an extremely sensitive colourist, but is not generally thought of as being naturalistic. The notes here, however, do document that he sought to remember very specific colour effects, though exactly what colour value can have been meant by ‘Dark Brownish’ numbered 1 that we can make out at the top of the list, remains to be established. There seems very little doubt, however, that it must have been so specific a nuance that he determined to erect a signpost that would enable him in time to recover that exact value from his memory.

Cotman’s observations provided the basis for a series of important works culminating in the present etching. We will examine those in part 2.

To be continued:-

David – I have lost my first response, but have emailed you images…..Many years ago I visited the Glyn Vivian Museum and Art Gallery Swansea in search of Welsh JSC drawings. They have a drawing of Croyland (see emailed image) and from them I have the most atrocious photocopy of which you will now have an atrocious copy. It is inscribed with date bottom right, but that is cut off. However it seems to read ’20th’ – a decent photograph will no doubt elucidate this. The inscription also has ‘Croyland’, not ‘Crowland’ as per print – presumably this was changed for some reason.

Best wishes Jeremy

Hi Jeremy

Thank you so much for this extremely quick response. I had no inkling about the Glynn Vivian drawing, but from your emailed image, it is certainly JSC’s on-the-spot drawing, and a splendid thing to boot. Will try and source a decent image to include asap.

Hi David,

Thanks so much for posting such informative and well illustrated accounts of Cotman’s views of Crowland. A very minor point, but I am pretty sure that Thomas Girtin did not accompany James Moore to Crowland in 1794 as you suggest. Girtin’s watercolour is worked from two drawings by Moore (TG0286a and TG0286a figure 1) both dated 12 September 1789 (one of which Girtin seems to have worked over, improving the amateur’s insecure perspective etc) and I suspect that it actually predates the tour to the Midlands that artist and patron undertook in the summer of 1794. Crowland would have been an unnecessary detour on their way between London and Lincoln, therefore.

All the best

Greg

Hi Greg

Thank you for the clariification. I will amend the text accordingly. For the interest of readers I will also include a link to your splendid online catalogue of the work of Thomas Girtin. It is interesting that you have concluded that Girtin probably never saw Crowland for himself. It suprised me that Cotman did not seem to know of Girtin’s watercolour, or the engraving of it. That might have deflated his sense of discovery, but if Girtin didn’t actually go there, we can at least grant Cotman some portion of his pride!