This is the twenty-seventh article in a catalogue of John Sell Cotman’s first series of etchings published in 1811. Here we conclude the discussion of plate 22 with a consideration of the significance of his plate of Crowland Abbey.

Croyland Abbey, Lincolnshire, 1811

Private collection

Photograph: Professor David Hill

At the end of part 2 we left Cotman in the summer of 1810 proliferating new styles, genres and initiatives. Amongst all this he tried his hand at etching. His first efforts are dated to June 1810 and remained unpublished but will be catalogued here after the published series. By 1 August he had completed The Manor House York (see Plate 2) and conceived a plan to issue a series. By the time of the Norwich Society exhibition of August 1811, the project was complete and he devoted his entire submission to the etchings.

Cotman’s turn to etching in 1810 proved surprisingly complete. By the time that he showed no.64 as ‘West front of Croyland Abbey, Lincolnshire’ at the Norwich Society in 1811, he was almost entirely committed to the medium. It was probably not always intended to be so, but Cotman threw himself wholeheartedly into every new initiative, and this one rewarded him for it. Subscriptions went well, and by the time that he published the complete edition in 1811 he could count subscribers to two hundred and forty copies. The price of the complete work was two guineas, so gross takings amounted to more than five hundred pounds.

The plate of Crowland Abbey was widely admired. Soon after he had finished it, Cotman sent a selection of proofs to his Yorkshire patron Francis Cholmeley of Brandsby Hall, near York. Cholmeley promoted them to his friends and reported: ‘Dr Goldie, an old Edinburgh colleague of mine was here for a few days on his way thither. He admired Croyland that you sent me so much and thought his friends in the North would do so too, that I gave it him in hopes it might help to propagate subscriptions.’ Francis’s sister, Katherine commented that she particularly admired the Croyland amongst a number of plates: ‘To say how nearly they resemble your pencil drawings is sufficient to prove how beautiful they are, but to me there is a strength and softness which excels even your original sketches’.

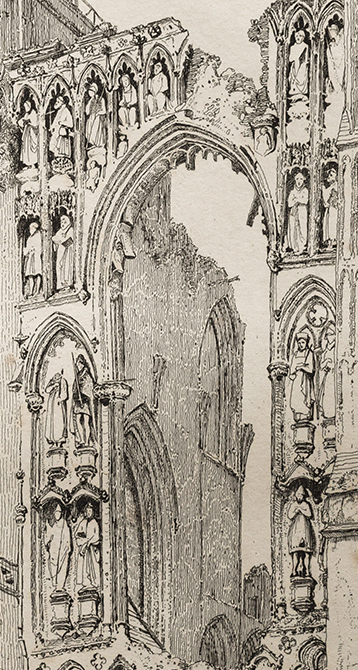

The etched line prints distinctly black as a source of strength, but we have had occasion to observe in previous plates how he gives life to the line by giving it an almost cardiographic quality, as if the hand as it passed over the paper were involuntarily registering the impulses of the heart.

In this etching, Cotman’s needle has rather run away with him and endowed the left buttress of the tower with four panels in its upper tier and three in the lower. In other respects, however, his expression of the architecture manages to convey a sense of the exquisite. The meticulously individuated louvres of the belfry arcade would have been beyond most other artists’ caring, as would the variously glazed, open, shuttered, patched and plastered panels of the church’s west window.

Click on any either image to open full-size in gallery view. Close gallery to return to this page

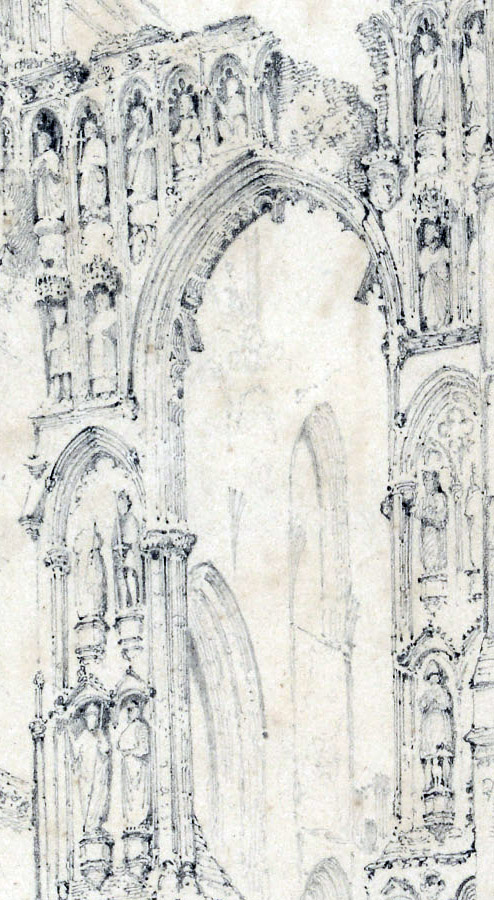

If we trace the detail of the sculpture back to the on-the-spot pencil drawing, and compare that with my comparative photograph, it becomes plain that Cotman’s original drawing records the sculpture as well as we would expect, with perfect fidelity to its appearance from this distance and angle. On the whole, however the drawing in the etching is more expressive and more highly developed than in the pencil. The louvres, for example, are greatly enhanced in interest, and pretty much every touch is given greater resolution and refinement. With the figures, whilst the pencil gives an accurate account of what he could make out from the ground, the etching takes those indications and refines them into deft graphic caricatures, like a miniature parade of Chaucerian pilgrims.

In reality the detail above is little more than two inches wide [53 mm to be precise]. Even the largest figure is no longer than my thumbnail. Despite the etching being 15 x 10 7/8 ins (380 x 277 mm) overall, when we look into the smaller details, they are pretty much at the limit of what we can resolve wit the unaided eye. So as in drawing, painting and etching, so it is on site: Standing on Cotman’s viewpoint, it is impossible to make out any more than we see here. Cotman’s principal achievement is to suggest the variety of the characters depicted, and to provoke further interest and investigation.

Notwithstanding that, it seems hard to imagine that Cotman’s depictions of the sculptures would have satisfied the scientific scrutiny of the Botanists worried about in his letter from Crowland (see above, part #1). Understanding the figures in the round, however, first requires the ability to see them in the round, and that would require scaffolding or more latterly a cherry-picker, a drone, or even a Lidar scanner. It is perhaps not surprising that the first proper systematic visual record was not accomplished before the photographs published in Jenny Alexander’s article in 2014. Cotman’s drawings and etching represent much more the beginning of an interest rather than the end. They are part of a movement to popularise interest in such things that was begun in the eighteenth century. In putting his artistic talents in the service of architectural antiquities he invested our experience of these subjects with imaginative and emotional appeal. It is sufficient that his characterisation of the architecture and sculpture is powerfully suggestive that each element would reward greater familiarity and engagement. The investment was slow, however, to provoke real effect. Apart from some emergency shoring-up, Crowland continued to moulder until the 1860s when proper restoration work began. Cotman, however, may be given some credit for being in the vanguard of a movement that shaped the impulse to conservation. His originality in a nutshell, is to have shown how such a subject might look when viewed through a lens imbued with feeling.

Summary of known states:

First published state

As editioned by Cotman for ‘Etchings by John Sell Cotman’, 1811, where plate 22.

Line etching, image 365 x 271 mm (14 1/4 x 10 3/4 ins) on plate 380 x 277 mm (15 x 10 7/8 ins) printed in black ink on soft, heavyweight, off white, hand-made rag wove paper, 474 x 340 mm

Inscribed on plate bottom left of subject ‘Published Jan 26th 1811 Norwich’; bottom centre of subject ‘Croyland Abbey, Lincolns’ and bottom right of subject ‘J.S. Cotman Del et Sc’.

Collection: Examples in various collections, e.g. Norwich Castle Museum NWHCM : 1956.254.24

Second published state

Line etching, image 365 x 271 mm (14 1/4 x 10 3/4 ins) on plate 380 x 277 mm (15 x 10 7/8 ins) printed in black ink on heavyweight ?machine-made wove paper, 493 x 353 mm

As editioned by H G Bohn in ‘Specimens of Architectural Remains in various Counties in England, but especially in Norfolk. Etched by John Sell Cotman’, 1838, Vol. 2, series 4, xv. Plate unchanged from 1811 edition except for some darkening of foreground, and darkening of shade on right buttress. The numeral ‘XV’ added top centre.

[details of right parts 1811 print and 1838]

Examples in numerous collections, e.g. Norwich Castle Museum, NWHCM : 1923.86.24

References:

Popham, 1922, no.24.

Alexander, Jenny, “‘Sadly Mangled by the Insulting Claws of Time’: 13th-Century Work at Croyland Abbey Church”, in John McNeil (ed.), King’s Lynn and the Fens: Medieval Art, Architecture and Archaeology, British Archaeological Association Conference Transactions, no. 31 (Leeds: Maney Publishing for the British Archaeological Association, 2008), pp. 112–133.

‘Croyland Abbey West Front Sculpture’, report for Anderson and Glenn (architects), (March 2014). Available as pdf download from University of Warwick: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/144395

Alexander, Jenny, “St Guthlac and Company: Saints, Apostles and Benefactors on the West Front of Croyland Abbey Church”, in Sue Powell (ed.), Saints and their Cults in the Middle Ages, Proceedings of the Harlaxton Medieval Symposium, no. 32 (Donington: Shaun Tyas, 2017), pp. 249–264.