This is the sixth part of an exploration of Jumieges in Turner’s footsteps. Here we continue consideration of the watercolour engraved for the second volume of Turner’s Annual Tour published in 1834.

Jumieges

Watercolour and bodycolour on blue paper, 140 x 190 mm, 5 1/2 x 7 1/2 ins

Tate, London, Turner Bequest TB, CCLIX 131

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-jumieges-d24696

Turner’s experience of Jumieges Abbey might have been somewhat distant, but he fully engaged with the river. Despite the topographic vagaries of the engraved watercolour, his memories of both traffic and weather were quite specific. In the foreground a rowing boat laden with passengers gives way to a passing steamboat, whilst beyond, a rainbow breaks through a veil of rain. John Ruskin, writing in Modern Painters, published in 1844 (Chapter 4, section 13; given in Works of John Ruskin Vol 3, p.400) called the effect:

the most perfect and faultless passages of mist and rain-cloud which art has ever seen. Wet, transparent, formless, full of motion, felt rather by their shadows on the hills than by their presence in the sky, becoming dark only through increased depth of space, most translucent where most sombre, and light only through increased buoyancy of motion, letting the blue through their interstices, and the sunlight through their chasms, with the irregular playfulness and traceless gradation of nature herself, his skies will remain, as long as their colours stand, among the most simple, unadulterated, and complete transcripts of a particular nature which art can point to.

He was actually speaking of a speciality of Turner’s younger contemporary Anthony Vandyke Copley Fielding, but this was just one of the myriad such effects comprehended by Turner :

Jumièges, in the Rivers of France, ought, perhaps, after what we have said of Fielding to be our first object of attention, because it is a rendering by Turner of [this] particular moment, and the only one existing, for Turner never repeats himself. One picture is allotted to one truth; the statement is perfectly and gloriously made, and he passes on to speak of a fresh portion of God’s revelation.* The haze of sunlit rain of this most magnificent picture, the gradual retirement of the dark wood into its depth, and the sparkling and evanescent light which sends its variable flashes on the abbey, figures, foliage, and foam, require no comment; they speak home at once.

Not that the passengers are listening at all attentively. They have just endured a soaking from the passing shower, and present a rather forlorn sight. Only the young woman in the prow has an umbrella. The other women hunch beneath bonnets and shawls, whilst the oarsmen appear deep in some discussion, even argument. Hardly anyone seems to pay the rainbow or sunlit abbey much heed, except for the seated woman who appears to lift her eyes in its direction, and the standing man in the stern who waves a staff aloft as if he were some Old Testament Prophet receiving the Word of the Lord.

Who are these people, and what are they doing? They don’t appear to be pleasure-boaters. The women wear peasant dress and the men knitted or cloth caps that identify them as countryfolk. It seems more than likely that this is a ferry, or a ‘bac’ as it would be called on the Seine.

La Mailleraie, 1831

lithograph

From Les Rives de la Seine, Trente Six dessins Lithographies par M Deroy, published in three parts by Ch Motte Paris 1829-31. Complete edition Paris 1831.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

La Mailleraie, 1834

Engraving

From Turner’s Annual Tour, 1834

Photograph by David Hill

The Seine is a big river, for most of this stretch at least two to three hundred metres wide, and until 1959 there were no bridges below Rouen. Even now there are only three. Crossings were made on the ‘bacs’ situated at regular intervals. Many survive today, including two at Jumieges, one not far west of the abbey and another a short distance north west connecting Yainville to Heurteville. In Turner’s day these crossing points were equipped with at least a rowing boat for foot passengers such as that shown here, but also with quite large (even unwieldly) shallow-drafted craft that could take animals or a carriage. Turner seems to have particularly associated the area with small boats beset by showers and rainbows. He also painted Chateau de la Mailleraie, a few kilometres downstream, and featured its ‘bac’ in the foreground, overarched by a rainbow. For Turner, clearly such conditions defined his memory of that stretch of the river.

Turner never forgot anything, and his memory shaped all that he drew or painted. It is perhaps the case that the present subject reaches back even as far as his very first watercolour.

Folly Bridge and Bacon’s Tower, Oxford, 1787

Pen and ink and watercolour on paper, 325 x 445 mm, 12 7/8 x 17 ½ ins

Tate, London, Turner Bequest TB I A

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-folly-bridge-and-bacons-tower-oxford-d00001

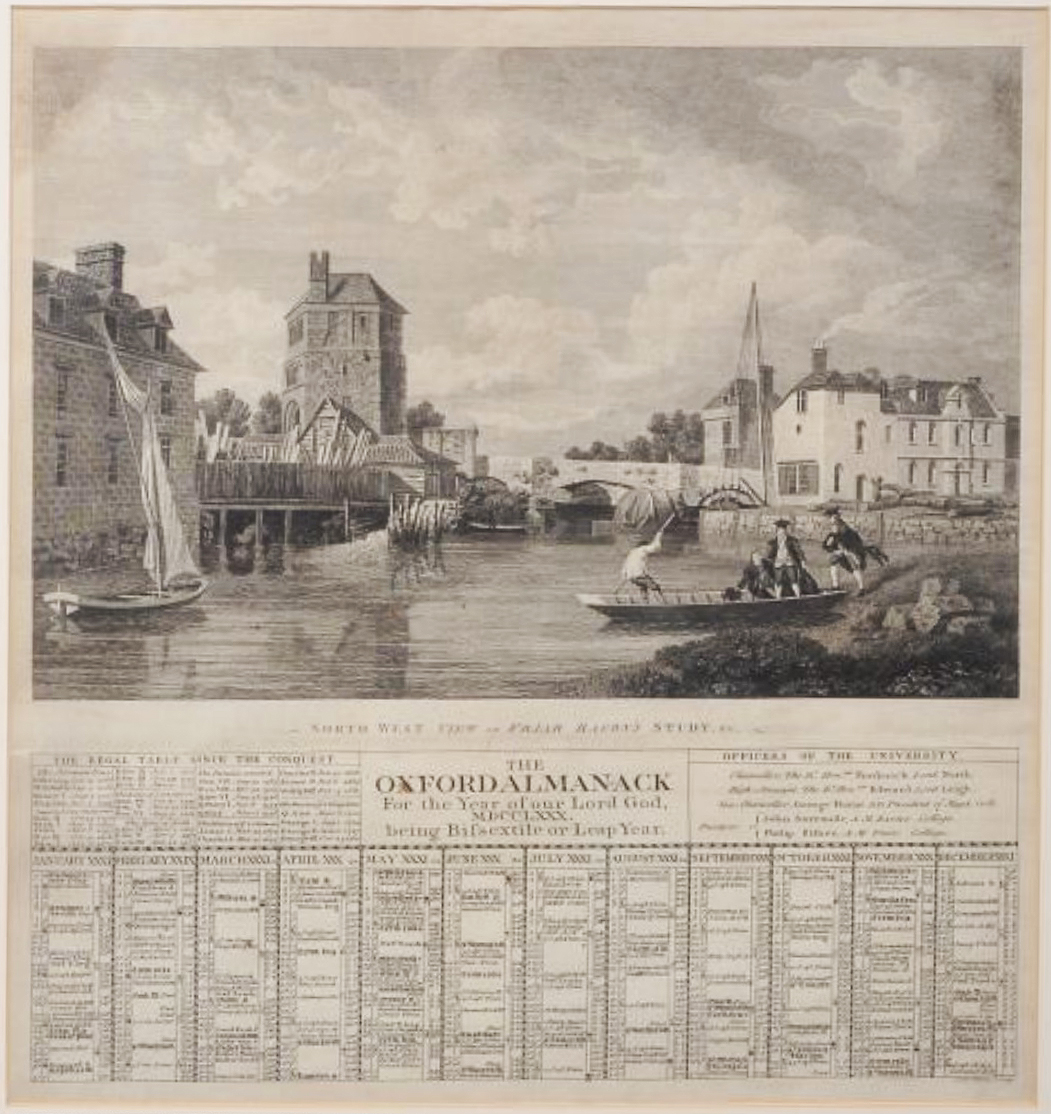

He painted Folly Bridge and Bacon’s Tower when he was a boy of twelve and possibly before he had ever been to Oxford. It is a copy of a subject by Michel Angelo Rooker that was engraved for the 1780 Oxford Almanack. In the foreground some academics step aboard a punt for a trip upon the river. It must have seemed a metaphor for all that he hoped for from life, and the boat remained a motif that would carry imaginative freight throughout his life.

North West View of Friar Bacon’s Study, &c,

Line engraving for the Oxford Almanack, 1780

Sold at Mallams auctions, 18 October 2017, lot 5

https://www.mallams.co.uk/auction/lot/lot-5—after-michael-angelo-rooker/?lot=86242&so=0&st=&sto=0&au=359&ef=&et=&ic=False&sd=1&pp=48&pn=1&g=1

But there is another aspect of the Oxford Almanack that provided an important foundation for his life’s work. The Oxford Almanack was in effect a single image calendar. Below the image was printed the University Calendar, and members of the University would put it up on their walls for reference. Thus the images were designed to sustain interest through repeated viewings for an entire year. Over time, one might notice a new detail, realise some new thought, or awaken to some new significance. Images today seem designed to satisfy exactly the opposite principles. Now we inhabit a complete blizzard of imagery; to almost none of which we pay much attention, still less muse over or examine for any subtleties. Everything has to be instantly understood and more or less arresting or amusing. The idea of an image not being entirely self-explanatory, or requiring puzzling-over, renders it invisible. The illustrations to Turner’s Annual Tour, however, were designed as the latter-day successors of the Almanack: to unfold themselves to the understating only over time, and to resist singularities or simplicities. This will no doubt exasperate anyone blithe with instant understanding of an image. We could perhaps return to the image of Jumieges over many months and find fresh aspects, but that might test the patience of the few that have persevered with the site thus far. Even so, there remain a few things that I would still like to point to.

To be continued