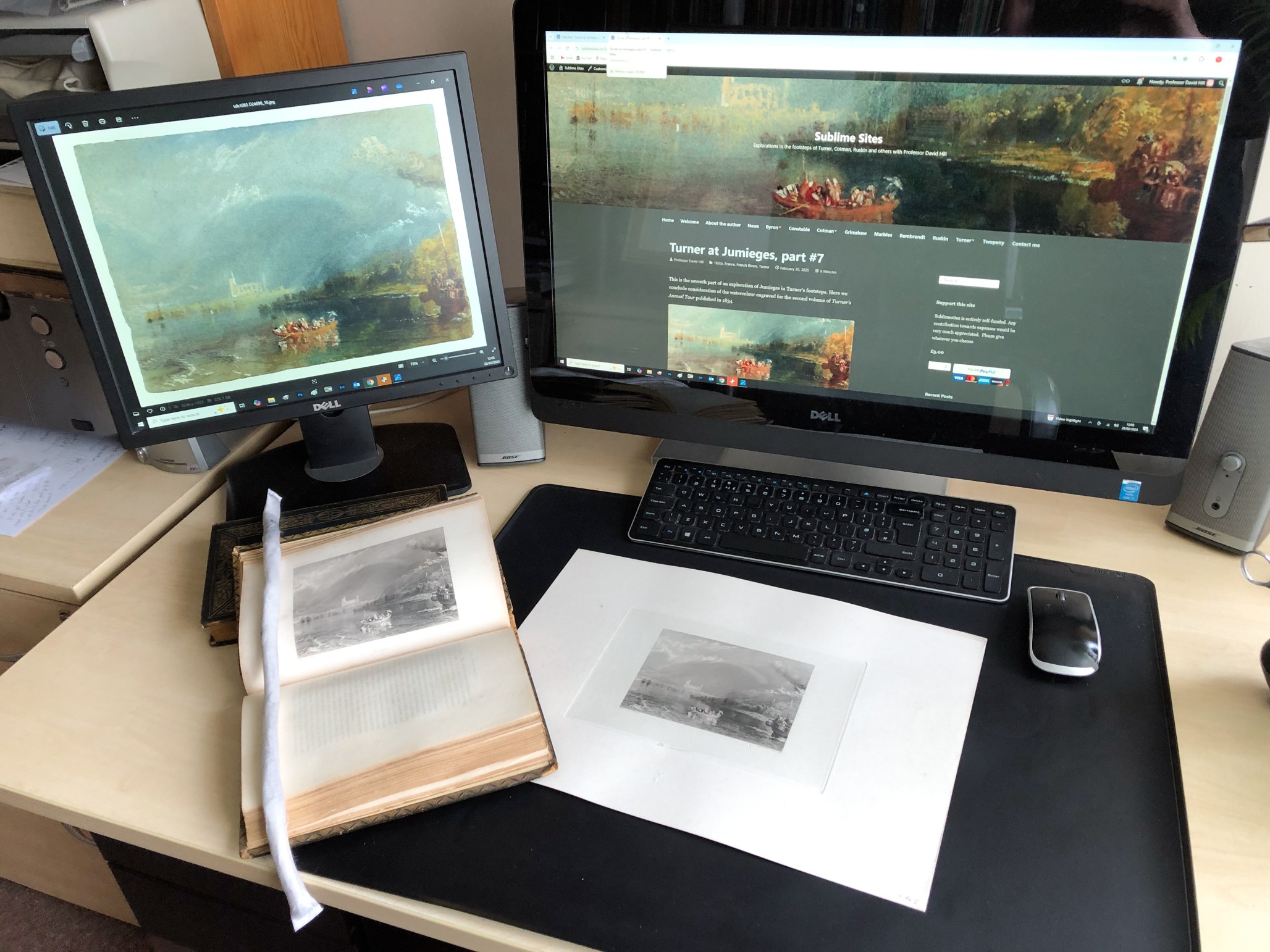

This is the seventh part of an exploration of Jumieges in Turner’s footsteps. Here we conclude consideration of the watercolour engraved for the second volume of Turner’s Annual Tour published in 1834.

Jumieges

Watercolour and bodycolour on blue paper, 140 x 190 mm, 5 1/2 x 7 1/2 ins

Tate, London, Turner Bequest TB, CCLIX 131

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-jumieges-d24696

The audacity of Turner’s composition of Jumieges does not appear to have been fully recognised. Whilst most commentators have spoken about the steam boat, and recognised that it is key to the action and the interpretation, no-one has properly acknowledged that it is barely part of the picture at all. We see only its stern, and a small fraction even of that.

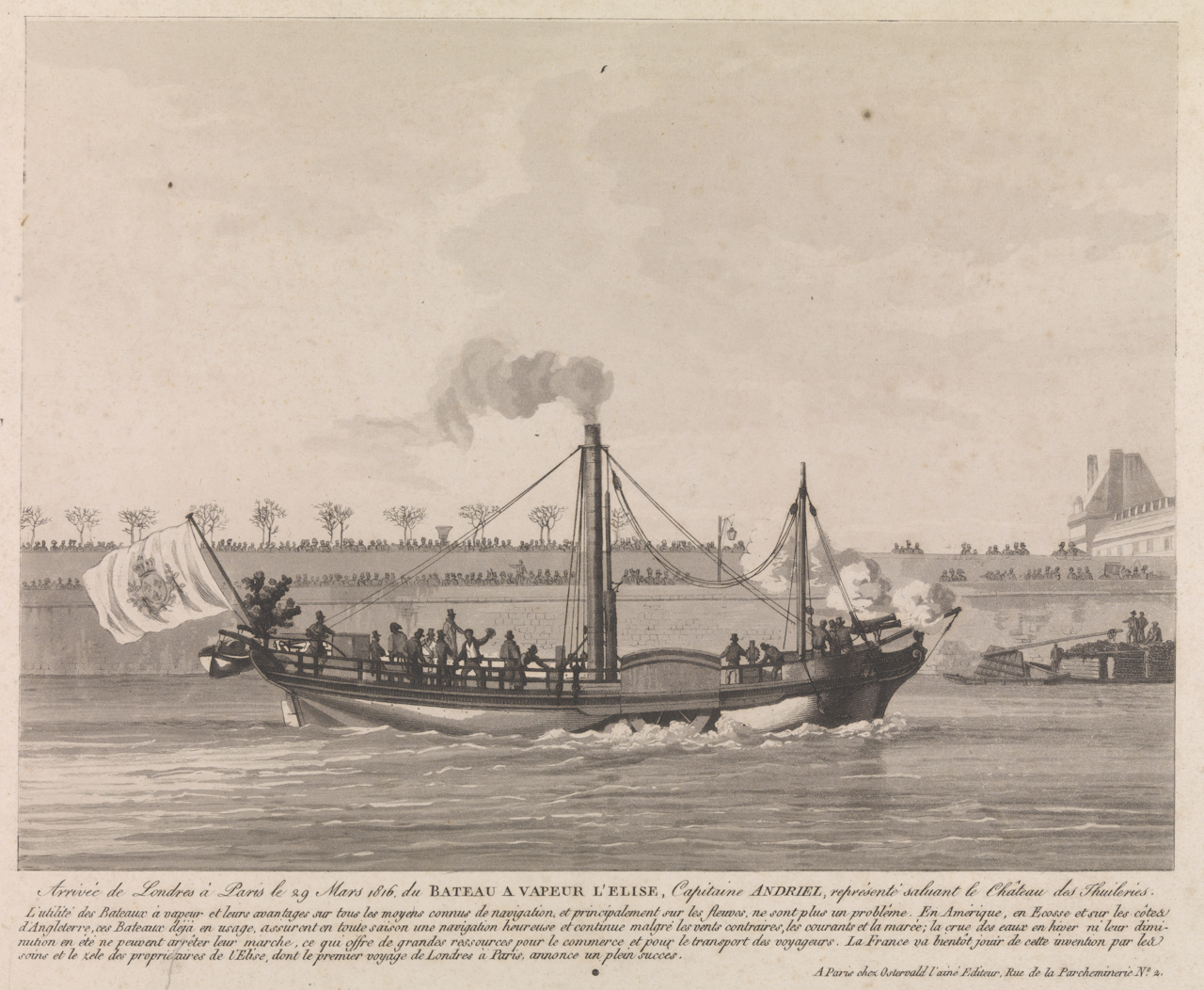

Even the very early steamboats were substantial vessels. It will probably be impossible to be certain which specific steamboat Turner has in mind, but the details correspond to those of the Elise. She was one of the most famous of the early steamboats on the Seine (full history given here). She was built in Dumbarton on the Clyde in 1814 and did service as the ‘Marjory’ on her home river before being transferred to the Thames. In 1816 she was sold, renamed the ELISE and on 17 March became the first steamer to cross the English Channel. She sailed from Newhaven to Le Havre and then up the Seine to Paris where she arrived to great acclaim on 29 March. The engraving above was issued to mark the occasion. She served several years on the Seine and evidently ended her days there. On source says that part of her hull was still visible on the banks of the Seine as late as 1888. We cannot say that the stern in the watercolour is certainly that of the Elise, for there were several other paddle steamers on the Seine by the later 1820s, but Turner’s and the Elise are near-identical. It remains an open question as to what was Turner’s source for these details. He might well have taken them from an engraving.

We might not know it was a steamboat at all except for the steam and smoke that trails in its wake. Nor is it entirely to be taken for granted that every viewer would immediately recognise the trails for what they are. John Ruskin, who perhaps wrote more perceptively than any other with regard to Turner’s knowledge of phenomena, devoted a fine passage to this specific effect in the first volume of his Modern Painters, published in 1844 (Chapter 4, section 13; given in Works of John Ruskin Vol 3, p.400):

…there is yet added to this noble composition an incident which may serve us at once for a farther illustration of the nature and forms of cloud, and for a final proof how deeply and philosophically Turner has studied them. We have, on the right of the picture, the steam and the smoke of a passing steamboat. Now steam is nothing but an artificial cloud in the process of dissipation; it is as much a cloud as those of the sky itself, that is, a quantity of moisture rendered visible in the air by imperfect solution. Accordingly, observe how exquisitely irregular and broken are its forms, how sharp and spray-like, but with all the facts observed … the convex side to the wind, the sharp edge on that side, the other soft and lost. Smoke, on the contrary, is an actual substance, existing independently in the air; a solid, opaque body, subject to no absorption or dissipation but that of tenuity. Observe its volumes; there is no breaking up nor disappearing here; the wind carries its elastic globes before it, but does not dissolve nor break them.‡ Equally convex and void of angles on all sides, they are the exact representatives of the clouds of the old masters, and serve at once to show the ignorance and falsehood of these latter, and the accuracy of study which has guided Turner to the truth.

‡ It does not do so until the volumes lose their density by inequality of motion, and by the expansion of the warm air which conveys them. They are then, of course, broken into forms resembling those of clouds.

Ruskin’s observation is rather beautiful and not a little important, yet manages to overlook the obvious. The steamboat, though a principal character in the play, is ostentatiously performing its part off stage. It is a bold and unusual pictorial device. There might be comparable pictorial examples, particularly in cartoons, but in mainstream art, particularly that of landscape it is certainly rare, if not positively outlandish.

Turner must have hoped that his viewers would wonder at this device. It is almost as if the steamboat will not be bound by the usual frame of representation, and requires new apparatus to accommodate it. As we have seen in the pencil sketches, the steamboat’s relentless progress affected Turner’s ability to come to terms with his situation. There is a distinct sense in the sequence of there being insufficient opportunity to construct a stable conception. The ostensible subject remained distant, whilst the locomotion from which it was viewed became the principal recollection. Turner, however, was never one to any allow any experience of the world go unreported, unquestioned and unrepresented, and he determined to make that new condition of experience his subject here.

The two boats contrast old and new modes of being in place but the balance of that equation is left very much open for consideration. Turner is rarely one for taking sides. As we have discussed in relation to other examples, perhaps it is a feature of all good art that it provides material for deliberation, and allows a space to permit a dreamwork in which the viewers can negotiate their own feelings and positions. For other references to this concept enter ‘dreamwork’ in the search box above right on his page.

The main event is occurring over the abbey. The ruins act like a lightning rod for the weather. The stones gleam in sudden light perfectly framed by a rainbow. It is almost as if the site was designed to act as a pole for the sublime. This is totally lost on the passengers being whisked away on the steamboat. The rowing boat offers more agency, and more time, and more exposure, but the older mode is not straightforwardly better. The passengers, after all, have been exposed to a soaking, and are more wrapped up in their discomfort than exulting in their experience. In truth being there is very much a mixed blessing.

So although Turner sees greater potential for engagement in the established modes, he acknowledges that the lived experience requires some fortitude. For him, this was no issue. He seems to have taken every opportunity to get out and enjoy whatever the elements threw at him. This might be the example that he set to his audience, but it is a different matter to what extent this might have been relished in practice.

Jumieges

Watercolour and bodycolour on blue paper, 140 x 190 mm, 5 1/2 x 7 1/2 ins

Tate, London, Turner Bequest TB, CCLIX 131

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-jumieges-d24696

Besides questioning what relations might be occurring within a picture, it is equally worth considering what relations are being constructed in relation to it. Perhaps the most important character of all in this staging is the viewer. It is always worth considering who is doing the viewing and where from. In this case the picture was clearly designed to bring this into play. Our implied viewpoint is at about the same height as the passengers on the steamboat, somewhere over the water, but quite where is unexplained. We could be on a steamboat travelling in the opposite direction, but the picture gives no clue by which we might situate ourselves. The uncertainty separates us from the action, literally dislocates us, and given the discomfort being shown by those involved, we might take our situation as something of a boon.

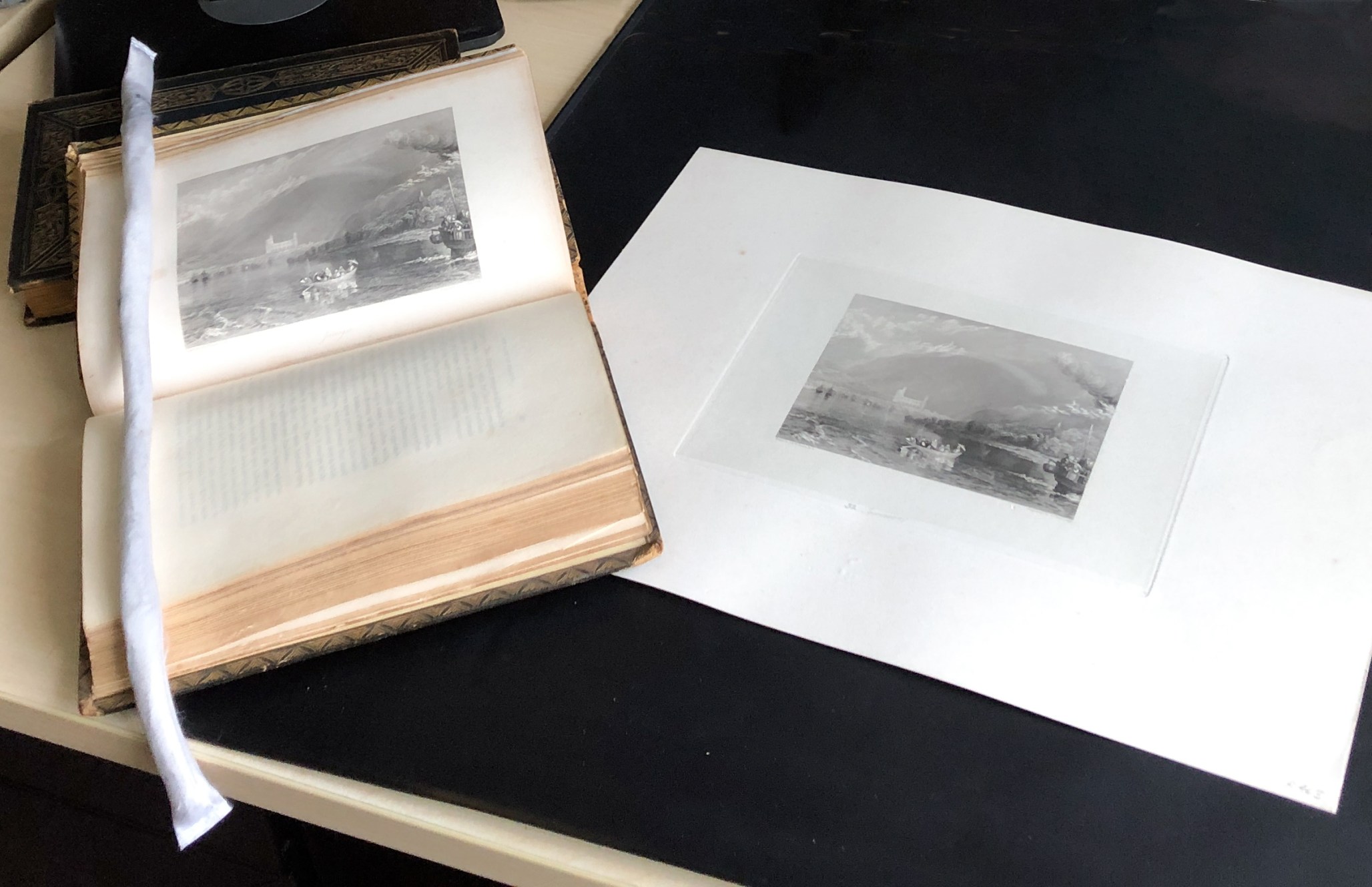

Click on any image to open full-size in gallery view. Close gallery to return to this page.

But what is our actual situation? In truth we are in an entirely different world. We are looking at a engraving in a book. There is comfort, shelter, and ease in our situation, perhaps even a drawing-room. Ours is a situation of privilege, perspective and evaluation. Their gaze seems designed to put us on our spot, to make us reflect more generally on our situation and its relationship to their world; to engender a dialogue around of modes and qualities of experience. They make the question is as much about us as them. Our guilty secret is that their discomfort is our pleasure.

In large measure “Landscape” as a genre is about NOT being there. It speaks to relationships with and within a changing world and it is the medium in which positions in relation to those relations are negotiated. Every new world has its own new technologies of representation, and it is in their spaces that the most relevant dreamwork occurs. In 1834, steel engraving was cutting-edge representational technology, and the illustrated books that it enabled were the ultimate high-risk and urgent cultural ventures of their time. Through such material citizens could form perspective on an ever-widening world, and adjust their knowledge to new epistemological foundations. Everything was in motion, and what was cutting-edge one year was redundant the next. In a future article we might give some thought to the rapid succession of formats in which Turner’s engravings were published. But for the time being it is perhaps sufficient to observe that the book form in which Jumieges was published might have been state of the art in 1834, but its moment was brief. Within four or five years that kind of book began to appear tired, and within ten years its technology of representation began to give way to something entirely new; photography.

Rain, Steam and Speed: The Great Western Railway, 1844

Oil on canvas, 91 × 121.8 cm

National Gallery, London, Turner Bequest, 1856

And as quickly as the technology of representation developed so did that of transportation. The Elise, first steamboat on the Seine in 1816, boasted 14 horse power. By the time of Turner’s visits in the 1820s there were vessels on the river of upwards of 100 horse power, and by the time the engraving appeared in 1834 it was possible to take a steamboat service from Le Havre to Lisbon. By the 1840s, however, river steamboat travel had (except for leisure excursions) largely given way to travel by rail. Ian Warrell (Turner on the Seine, 1999, p.160) was surely right to see the themes of Jumieges as precursive of Turner’s famous painting of Rain Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway, painted exactly ten years after Jumieges was published, and showing a steam train crossing the Maidenhead viaduct at the (then) mind-boggling speed of forty miles per hour. Warrell points out that both compositions contrast the new mode of travel with a party in a rowing boat. It seems plain that Turner’s conception of the old mode had mellowed by 1844 into something more nostalgic, whilst his feelings for the new had lost none of their ambivalence.

Nearly two centuries later the technology of representation has changed utterly but the issue of our relationship to the world is perhaps all the more important. Do we even care about the real. It that not just the grey, uncomfortable interval between sleep and a screen? Do we not exult in the way that our psychospheres are free floating? Do we not positively prefer to inhabit only the representation? Such questions were the staple of art-historical discourse throughout my career from the 1970s, but Turner’s Jumieges invoked those same themes two hundred years ago. Technology, in the form of the steamboat, carries us out of the world. But even in the old world, where there is a possibility bearing witness, people were so wrapped up in themselves as to be distracted or heedless when the world made itself sublimely manifest. Turner’s art is a constant reminder to look up and take notice of the world. It should remain the duty of an artist to make us think about where we are in relation to the world, and to point us towards the things with which we might be loosing contact.