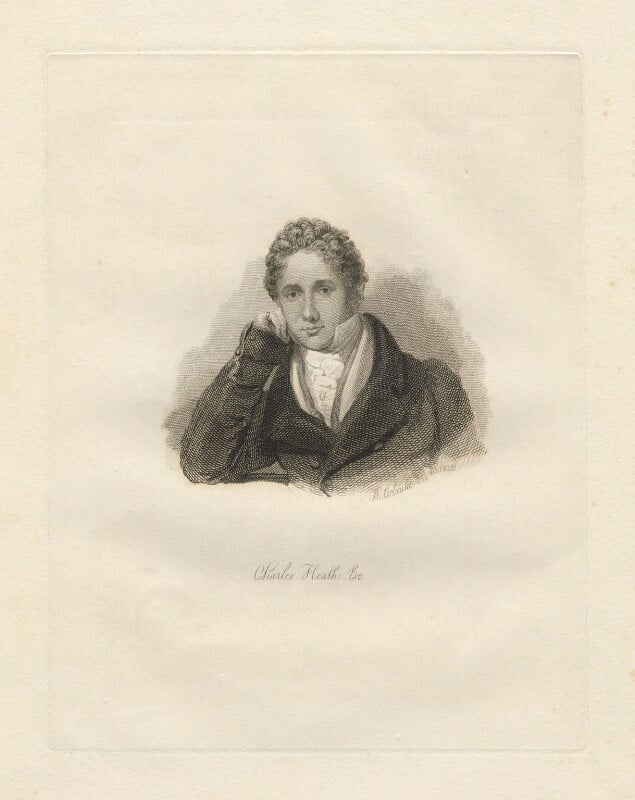

Origins and development: Charles Heath and the Annuals

This is the second part of an account of the various editions of Turner’s engravings of the Rivers of France, one of the most beautiful, extensive and important of Turner’s published topographical series. Here we trace the origins of the project leading to the appearance of the first edition.

by Mary Dawson Turner (née Palgrave), after Henry Corbould

etching, (1822)

NPG D22578

© National Portrait Gallery, London

The project was conceived and promoted by Charles Heath. He was one of the best engravers of the early nineteenth century and during the second decade his studio became one of the leading suppliers of engravings for books. He employed numerous engravers, and in so doing helped train an explosion of production in the following decades. In the process he amassed a considerable fortune and the means to capitalise illustration projects of his own.

His story has been well explored by his descendent John Heath in ‘The Heath family engravers 1779 -1878. Volume 2: Charles Heath and his sons Frederick & Alfred’ (Scholar Press, 1993). Charles Heath played a leading role in a major expansion of literary and artistic culture and his work with Turner made an important contribution to that.

Pope’s Villa, 1811

Etching and engraving on cream wove paper, Sheet: 9 5/8 × 13 3/8 inches (24.4 × 34 cm), Image: 6 7/8 × 8 15/16 inches (17.5 × 22.7 cm)

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, USA, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.13238

https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:38163

His first contact with the artist was through an engraving of Turner’s painting Pope’s Villa in 1811. The landscape work was done by John Pye, but Charles Heath added the figures. Turner is on record as having been surprised by the luminosity of the effects achieved by Pye.

Click on any image to open full size in gallery view. Close gallery to return to this page

Crook of Lune, 1821

Etching and engraving, Sheet: 9 1/16 × 12 5/8 inches (23 × 32.1 cm), Image: 7 9/16 × 11 inches (19.2 × 27.9 cm)

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, USA, Paul Mellon Collection

https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:37003

Ingleborough from Hornby Castle Terrace, 1822

Etching and engraving, Sheet: 10 3/4 × 15 3/8 inches (27.3 × 39.1 cm), Image: 7 1/2 × 10 11/16 inches (19.1 × 27.1 cm)

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, USA, Paul Mellon Collection

https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:37004

Kirkby Lonsdale Churchyard, 1821

Etching and engraving, Sheet: 12 × 15 1/16 inches (30.5 × 38.3 cm), Chine collé: 11 11/16 × 14 3/4 inches (29.7 × 37.5 cm), Image: 7 3/4 × 11 1/16 inches (19.7 × 28.1 cm)

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, USA, Paul Mellon Collection

https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:36984

In 1822 Charles Heath was himself employed to engrave some of the Turner subjects in Thomas Dunham Whitaker’s History of Richmondshire. This series of twenty engravings is renowned for its variety of weather and atmospheric effects, and Charles Heath was first drafted in to finish a plate of Crook of Lune and then to engrave two subjects entirely in his own right, Ingleborough from Hornby Castle Terrace and Kirkby Lonsdale Churchyard. These are large plates and Heath was paid 80 guineas for each, and twenty-five guineas just for finishing Crook of Lune. For an engraver whose principal reputation was for figures and portraits, Heath made a superb job of these landscapes. Perhaps more importantly the work provided him with weeks of immersion in Turner’s imaginative world, and closer familiarity than almost everyone else with the artist’s unique aesthetic qualities.

TItle page to the first volume of sixty plates, 1832

The experience appears to have inspired Heath’s belief in the artist’s importance sufficiently to commission for engraving an extraordinarily ambitious series of watercolours of Picturesque Views in England and Wales. By universal acclaim this is regarded as the core document of Turner’s career. Between 1825 and 1837 ninety-six subjects were engraved. Heath used his experience, reputation and contacts to secure and direct the services of the very best craftsmen. His knowledge of the publishing world enabled him to bring together a consortium to publish the prints and their accompanying letterpress to the highest standards. He also used his fortune to back the project to the hilt so that no aesthetic compromise would be brooked. Batches of four engravings appeared at quarterly intervals (sometimes longer) in what must have been one of the most wonderful serial works in the history of print publishing. It is a nice coincidence that the first volume of sixty plates was concluded and bound in the same year of publication as the first volume of Turner’s Annual Tour.

It was perhaps commercially unfortunate for England and Wales that the period in which it was published was also one of revolution in print publication. England and Wales was engraved on copper, which could only be printed in limited numbers. Just as it began to appear it was overtaken by engraving on steel plates. The still-standard account of the development of the new medium is by Basil Hunnisett, ‘Steel-engraved book illustration in England’ (Scholar Press, London, 1980). Steel being so much harder than copper, it was capable of extraordinary subtlety of tone and detail, but more importantly yielded a comparatively limitless number of impressions without showing and serious signs of wear. All of a sudden the highest-quality engraving was available in vastly greater quantity, at a fraction of the cost, to a much wider public. It is testimony to Heath’s belief in England and Wales that he persevered with it despite a constant battle against financial headwinds. It is also testimony to Heath’s business acumen that he saw the writing on the wall, and adjusted his focus to capitalise on working with the new medium.

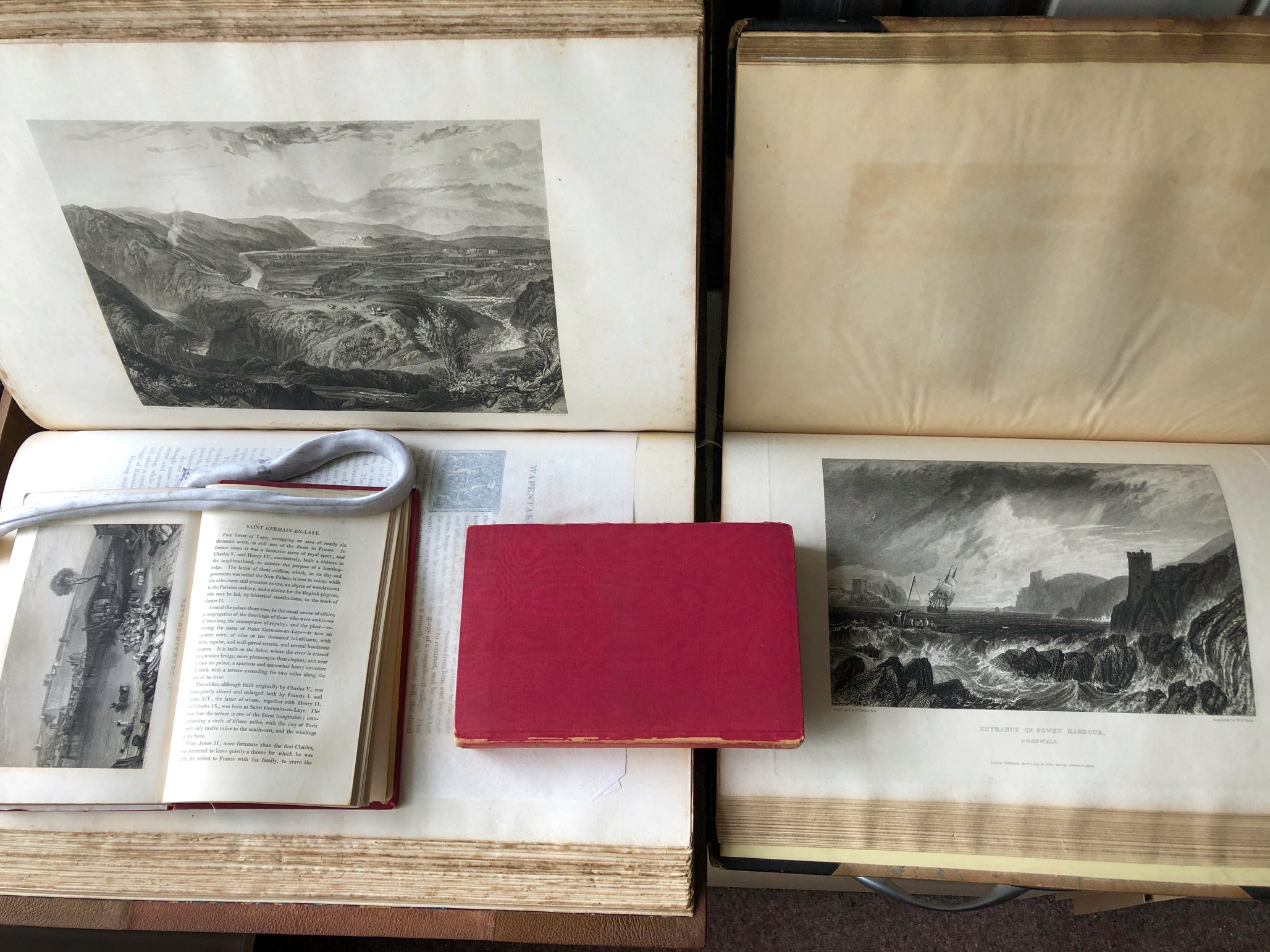

Photograph by Professor David Hill

In the later 1820s the most significant growth in the book market was in ‘Annuals’. These were books specifically designed to appeal as Christmas and New Year presents, predominantly bought by men for women. They consisted in the main part of more-or-less sentimental literary bon-bons, and a few engravings. They were generally small, designed to be read intimately and privately anywhere. The introduction of steel engraving made it possible to produce them in large quantity, sufficient to make them affordable, generally around 12/- per copy, and generally prettily bound. Within just a few years the summit of publishing shrank from tomes the size of a medieval Bible requiring a library to handle and display them, to gem-like treasures that could be perused in a bower in the garden. I have previously made observations in relation to this

but in this context it is striking that the large-tome production of Turner’s History of Richmondshire was completed in 1823 and Turner’s Southern Coast in 1826. Each of these is the size of a paving slab and weighs almost as much, and represents the very finest that artist, engraver, papermaker, printer, binder and publisher could conspire to produce. Yet even this pinnacle contained the seeds of its own dissolution. Heath’s first Annual was in the bookshops before the end of 1827.

Charles Heath was not the first to enter this market, but his contribution to it in the shape of ‘The Keepsake’ quickly became regarded as the benchmark for quality. Heath solicited contributions from some of the best-known writers of the time. Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley contributed, Sir Walter Scott, Wordsworth, and many others, often at great expense to Heath, but the general tone of the wider content was at best, sweet, romantic, and untaxing; at worst mawkishly stilted and posturing. Each issue featured twenty or so illustrations, always top-quality in terms of engraving, but nonetheless heavily loaded towards female or romantic subjects, many of the former engraved by Heath himself. The proprietor, however, was careful to elevate the mix in terms of seriousness and proper Romanticism and from the beginning each issue contained a couple of designs by Turner, and sometimes other significant artists such as John Martin or Richard Parkes Bonington. The first issue appeared in 1828 and was pitched at one guinea, in a slightly larger format that the others.

Heath’s masterstroke, however, was to bind The Keepsake in fuscia silk. He was completely brazen in his appeal to the Christmas/ New Year present market, and successful. The books sold in thousands, and whilst other Annuals came and quickly fell by the wayside, and the craze petered out after ten years, The Keepsake maintained a market for decades, and its final issue appeared in 1857. In all Turner contributed seventeen subjects between 1828 and 1837; most of them of some significance within his oeuvre. When Heath came to launch Tuner’s Annual Tour late in 1832, he prepared the market by including two Turner Loire subjects, Saumur and Nantes in the Keepsake for 1831, and two Seine subjects, St Germain and Marly in the Keepsake for 1832. He kept interest going by including two further Seine subjects Havre and The Palace of the Belle Gabrielle in the Keepsake for 1834.

Photograph, Professor David Hill

The Keepsake was right on the cultural cutting edge, and in many ways formative of it and the Annuals proliferated to reach a peak of sixty-two examples offered at Christmas 1831. The area offers an extraordinarily rich insight into the cultural dynamics of the period, and is ripe for a great deal of further consideration, but for the present we will confine ourselves to Heath’s involvement as it contributes to our understanding of Turner’s Rivers of France.

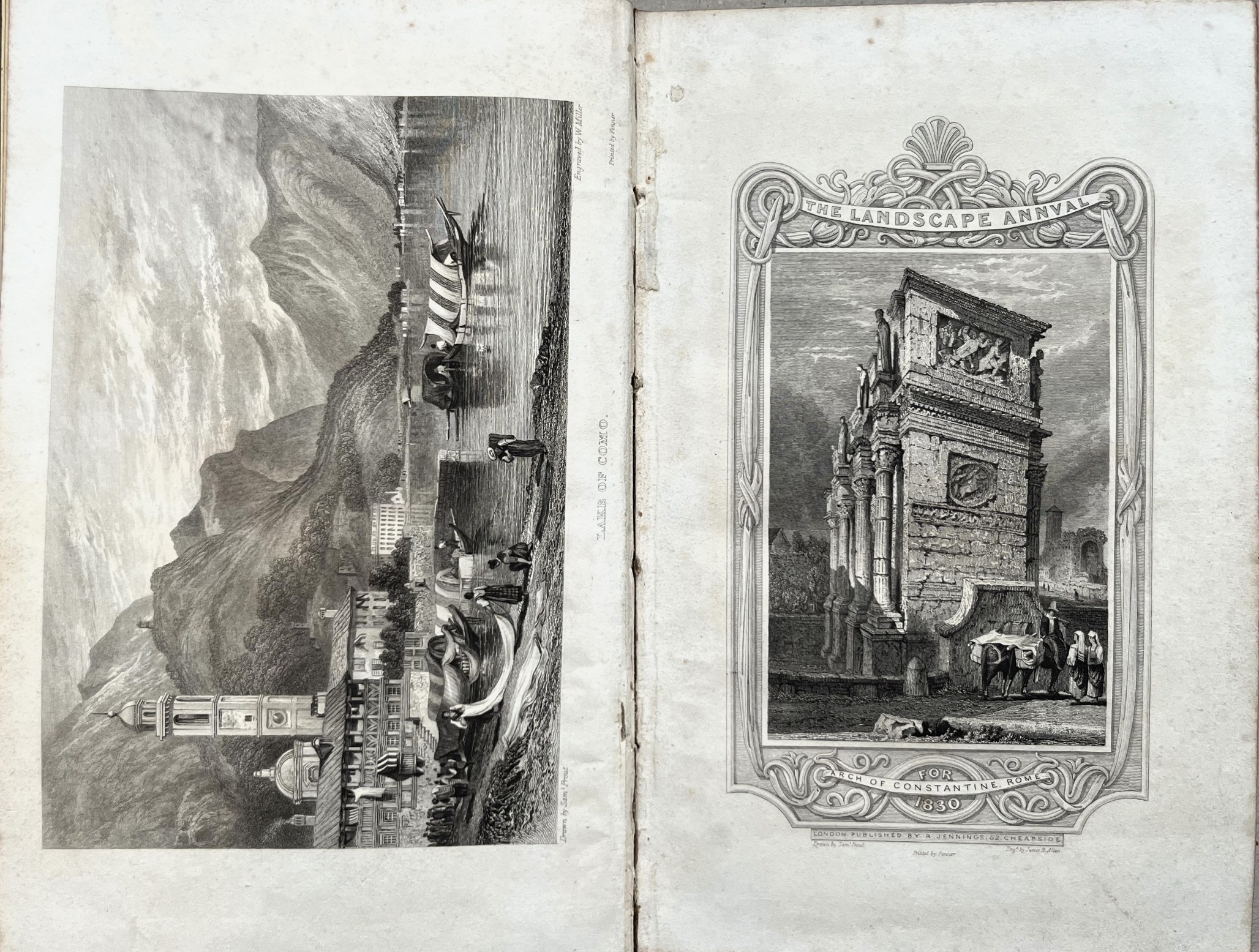

From 1832 Heath transferred publication of The Keepsake to Longman & Co, and in the couple of years before that he worked with the same publisher to develop two additional titles to run alongside The Keepsake. The market for the compendium Annuals like The Keepsake was becoming very crowded, so new strategies were called for. In 1830 Heath worked with publishers Jennings and Chaplin to introduce a new format of a single-artist travel book, about the same size and quality as The Keepsake. This was presumably designed to broaden the appeal across the sexes, and to cater for the increasing market for continental travel. The first volume of Jennings’ Landscape Annual was devoted to The Tourist in Switzerland and Italy was illustrated by twenty-six plates by Samuel Prout ‘engraved under the direction of Mr Charles Heath’. With a book-length travelogue text written by Thomas Roscoe, it proved a great success and spawned a follow-up volume for 1831 illustrated by Prout and engraved under Heath’s direction and that was continued in subsequent years by volumes illustrated by J D Harding.

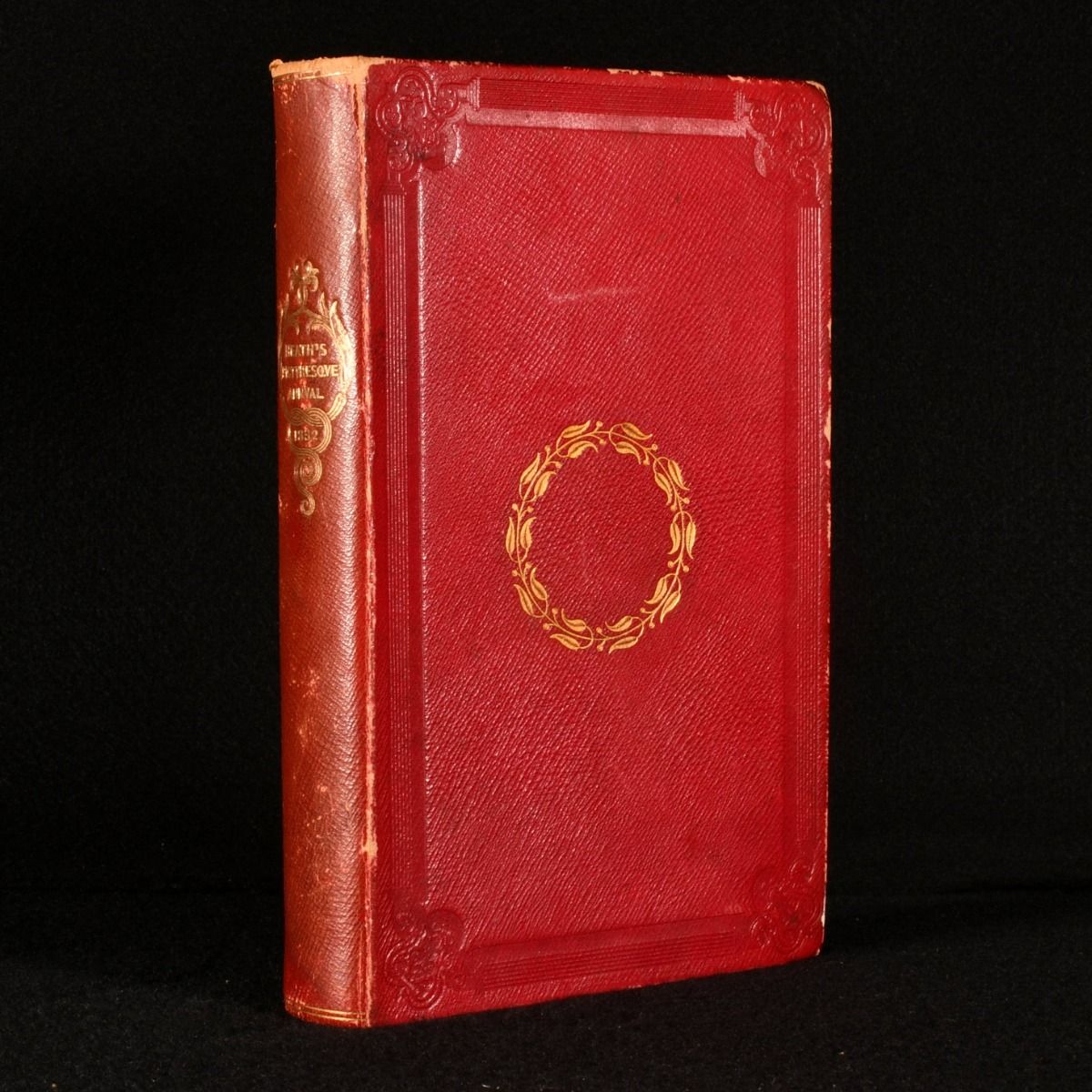

Heath’s Picturesque Annual for 1832

As published in crimson binding.

Images courtesy of Rooke Books

After only two years Heath parted company with Jennings and Chaplin in order to produce a rival series with Longman & Co. Heath’s Picturesque Annual for 1832 appeared late in 1831 presenting twenty-six ‘Travelling Sketches in the North of Italy, the Tyrol, and on the Rhine’ by Clarkson Stanfield engraved on steel by all the best landscape engravers. The plates were accompanied by a book-length text by Leitch Ritchie, who was one of the most ubiquitous travel writers of the day, and the whole was strikingly bound in bright crimson leather. Since the mid 1820s Clarkson Stanfield had steadily heightened his reputation for landscape illustrations and by the early 1830s he was at least as popular as Turner, and even to be preferred by many. The venture was a resounding success, selling some 7000 copies, almost exactly equal to the sale of the same year’s Keepsake.

Amboise, the bridge and castle from downstream, sunrise, 1826-1830c

Watercolour with bodycolour and pen and brown ink on blue paper, 132 x 187 mm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

https://ashmolean.org/collections-online#/item/ash-object-88617

It would appear, however, that Heath always esteemed Turner above all the others, and sometime around 1830 he managed to persuade the great lion to deploy his powers in a sole illustrated book of his own. Turner produced for Heath a series of watercolours illustrating a tour along the river Loire. Turner had made a tour of northern France in 1826, including a systematic survey of the Loire, possibly with the Annuals market in mind. Heath commissioned watercolours for publication in The Keepsake, but those were highly finished in a similar style to those that Turner was making for Picturesque Views in England and Wales. For the Loire project, however, the artist supplied much smaller works; watercolour on blue paper, painted much more rapidly and spontaneously. In comparison to Turner’s other work for Heath, the Loire drawings must have seemed much less resolved, much more like sketches. This is a truly radical departure for Turner, and might have posed something of a challenge for Heath’s expectations. Certainly it is the case that no series that Turner made for engraving had ever come even close to the spontaneity and ad hoc inventiveness as these. The bravura of the drawings must have posed endless challenges for the engravers, but they exuded a vital sense of Turner being there. The watercolours offered a parade of scintillating effects to which the artist bore personal witness and the engravers translated these into some of the most sublime images ever achieved in the medium.