This is the thirty-first article in a catalogue of John Sell Cotman’s first series of etchings published in 1811. Here we continue an appendix of unpublished plates. Along with the previous plate, this is the earliest dated of all Cotman’s line etchings.

An Old Wooden Cottage; A Pond in the Foreground, 1810

Private collection (a descendant of the Cholmeley family)

Photograph: Professor David Hill

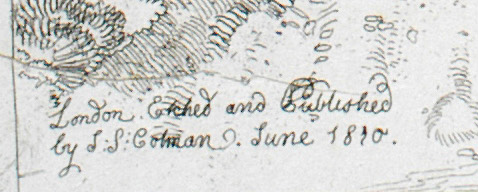

This is an upright composition of a rural village street. The principal subject is an extremely dilapidated weatherboarded house. This stands at the junction of a rutted village street with a lane to the right. There are old buildings opposite and further down the street, and to the right. In the foreground the road passes through a ford. To the left an old woman carrying a load on her back walks along a pavement into the street with a child dressed in a pinafore. The child is carrying a jug upon her head and appears with very fine hair appears no more than four or five years old. Beyond, on the opposite pavement, two boys play. One is seated; the other kneeling, and they are perhaps playing marbles. Above them hangs what appears to be an inn sign, although it remains blank. It does appear, however, that the principal building functioned as an inn. Above, in the sky, a significant flight of birds approaches, perhaps swans or geese. There is no inscription to indicate any identification, but Cotman has inscribed in the plate lower left: ‘London Etched and Published/ by J.S.Cotman June 1810’.

The date makes it, with the similarly inscribed Wooden Church Tower (see unpublished plate #1) Cotman’s earliest known line etching. Indeed both A E Popham in the his 1922 list of Cotman’s etchings (no.351 and p.242) and Sydney Kitson in his Life of John Sell Cotman published in 1937 (p.139) cite an impression once belonging to Dawson Turner and then in the possession of A.J.Finberg, that is inscribed by Dawson Turner ‘This is Mr Cotman’s first etching’. I have not myself seen this impression, but there is no reason to doubt it, or the belief in which the inscription was written. No-one at that time, however, seems to have been aware of the existence of the Wooden Church Tower which is similarly dated. That is much smaller and more tentative than the present plate, which is actually, as Kitson observes: ‘a good piece of work’. In fact it is quite accomplished, and it seems quite obvious that the Wooden Church must have preceded it. I think we may be certain that the Wooden Church and the present plate constitute Cotman’s first essays in line etching, but for the sake of complete accuracy I should admit that, Popham 1922 p.240 records that Cotman himself described a softground etching of a Cottage with Water Butt and Steps as his first etching. Cotman’s work in that medium lies outside the scope of this catalogue, but would provide someone with a wonderful field of study.

Kitson observed that ‘Only two impressions of this etching are known to exist’. One was that inscribed by Dawson Turner and the other was inscribed by Cotman himself: ‘Only ten proofs printed plate destroyed.’ Frustratingly, Kitson did not say where he saw that impression. Oddly, Kitson does not mention that he had seen two more impressions and recorded them in his notebook for 1928-29 preserved at Leeds Art Gallery [follow link]

Cotman had sent two different states as specimen gifts to his Yorkshire patron Francis Cholmeley and they had descended in the family. I saw these in 2004 and was kindly allowed to photograph them, and those are illustrated here scanned from twenty-year old 35mm slides. The earlier state is inscribed by Cotman ‘’A proof plate only 12 struck off’, and the second ‘retouched and destroyed’. It is interesting to have documentation in this case of the actual number of trial proofs that Cotman took of this impression. It seems likely that other proofs were taken in similar number. The Cholmeley proofs are the only ones that I have personally verified, but Norwich Castle Museum does have another impression of the first state.

Comparison of the two states reveals the order of events. Cotman took twelve proofs of the plate at the point he had etched all of the principal forms and details. He then regrounded the plate and overworked it with cloud and tone in the sky, as well as much enriched tone in the buildings. In the second immersion in the acid, however, the new ground failed to hold up perfectly and smutted in various places in the sky and around the edges. He took a further ten proofs, but then felt compelled to destroy the plate. It is perhaps a shame that he didn’t take more confidence from Rembrandt’s example, whose etchings frequently bear signs of mishap. So much so, indeed, that scholars throughout the ages have taken his scratches, smuts and accidents as vital signs of the artistic life that courses through them.

It is a double frustration that Kitson does not give the source or authority for his unequivocal identification of the subject of this plate (Life, p.139): ‘It represents a group of cottages with a pond in the foreground, a scene at Lakenham, near Norwich.’ Lakenham is now an inner city suburb of Norwich, occupying ground south of the city centre between the castle and the river Yare. There are a few drawings in the Norfolk Museums collection that are identified as Lakenham, but none offer the remotest correspondence with the present subject. There is a softground etching by Cotman called Cottage at Lakenham, but that likewise offers no close comparison. We can see Kitson approaching the identification of the present subject when he saw the two impressions in the Cholmeley family collection in 1929 he noted:

(4) 1st state (?) Lakenham. London etched & Published by J. S. Cotman June 1810. ‘A proof plate only 12 struck off.’

d[itt]o 2nd state. ‘retouched & destroyed.’

but it is unclear when or why the speculation solidified into certainty.

The identification of the subject must thus rest unresolved, but there is perhaps one further line of speculation to deploy. Such weatherboarded buildings are most characteristic of the south-east, and Kent in particular. This example appears to be of some age, and the planking of oak, which would suggest considerable antiquity, probably prior to the seventeenth century. It is presumably a place in which Cotman spent some time, and had sufficient association to want to draw it and, moreover, commemorate it in one of his first etchings. Given that Cotman implies by the inscription that it was etched in London, perhaps it was in the same locality that he learned to etch. At present we know nothing of those circumstances, but by producing this line of thought to its culmination, it seems possible that the same location also provided him with the subject of the Wooden Church.

As is usual with Cotman his figures are interesting. The old lady would have impressed Van Gogh as a study in grinding application to labour. She has probably spent a long lifetime bent under some load or other. Here it is possibly laundry, being carried home from the local wash house. The barefoot child has all this to look forward to, but even now has to make some contribution to the effort. Here she carries a pot on her head, possibly full of clean water from the pump, or perhaps to be filled with ale at the inn. The boys might well be amusing themselves at play, whilst their father carouses inside.

The building itself could stand as a cathedral of Cotmania; a splendid monument to rickety bodging and patching-up. Although this composition was abandoned, he did carry a similar subject of The Old College House at Conway to completion (see Plate #16). We have already noticed there that Cotman so often included timbers propped up against walls that they might be taken as something of an autograph. Here, the prop on the corner is a principal feature of the whole composition. Remove it, and the entire structure will collapse. It seems likely that Cotman projected so much self-identification into it that he might even have thought of finishing the inn sign with something more emblematic. What could be finer than raising a glass in The Cotman Arms?

Summary of known states:

Unpublished Proof: state #1

Line etching, within key line on plate 14 3/8 x 10 7/8 ins printed in black ink on heavyweight, stiff, white wove paper

Inscribed on plate lower left ‘London Etched and Published/ by J.S.Cotman June 1810’

All the main detail completed.

Collection: only two impressions verified:

i) Private Collection, a descendant of the Cholmeley family, inscribed by Cotman in ink across lower edge: ‘A Proof plate only 12 struck off’

ii) Norwich Castle Museum: NWHCM : 1949.141.1

iii) An impression formerly in the collection of A H Finberg cited by Popham 1922, p.242 and Kitson 1937, p.139 inscribed by Dawson Turner in pencil ‘This is Mr Cotman’s first etching’. It is not clear which state this might be, but Kitson’s reference implies state #1.

Unpublished Proof: state #2

Line etching, within key line on plate 14 3/8 x 10 7/8 ins printed in black ink on heavyweight, stiff, white wove paper

Inscribed on plate lower left ‘London Etched and Published/ by J.S.Cotman June 1810’

Heavily overworked to deepen tone of buildings and foregground. Sky added.

Collection: only two impressions known:

i) Private Collection, a descendant of the Cholmeley family, inscribed by Cotman in ink lower right ‘retouched & destroyed’

ii) Another impression of ?The same state cited by Kitson 1937 p.139 inscribed by Cotman ‘Only ten proofs printed: plate destroyed’