This is the second in a series of seven articles that will catalogue an important group of drawings by John Ruskin at King’s College, Cambridge. For general notes on the collection see under article #1.

2. Window in the Ca’ Foscari, Venice, 1845

Window in the Ca’ Foscari, Venice, 1845

Pencil, pen and ink and watercolour, 13 x 9 3/4 ins, 330 x 236 mm

King’s College, Cambridge

Photograph: David Hill

By courtesy of the Master of King’s College, Cambridge.

Pencil, pen and ink and watercolour on white (or buff) wove paper measured 12.07.2012 by DH (sight) 330 x 236 mm, 13 x 9 1/4 ins. Found framed in original William Mason frame and backboard, but with a newer mount in need of changing, and a quantity of debris under the glass.

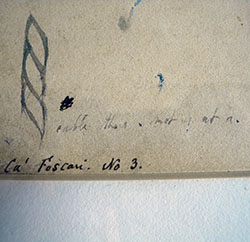

Inscribed in Ink, lower left: ‘Ca’ Foscari No.3′ and in grey watercolour, above; ‘cable thus not as at n [i.e. below right, under capital]’, in pencil, top right; ‘cusp’, ‘section at 1 and at 2’ and in ink; ‘cusp’, ‘section at 1 and 2/ alike and inside the/same’.

With an old label on the backboard of William Mason, Carver and Gilder, Ambleside, inscribed in ink by Robert Cunliffe: ‘SL [i.e. Seven Lamps of Architecture, published 1849] Window in Ca’ Foscari Venice original drawing by J Ruskin from which Plate VIII of Seven Lamps was made purchased from Miss H Baillie’

Detail of backboard, with the label of William Mason of Ambleside, who framed the watercolour for Robert E Cunliffe about 1900.

Provenance:

The artist to

Miss H Baillie by whom sold c.1900 to

Robert E Cunliffe and by descent to

Guy Barton, by whom bequeathed 1981 to

King’s College, Cambridge

Exhibition and Publication:

John Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, 1849, pl.VIII (and pl.IV), pp. 88-9, 203.

E.T. Cook and A. Wedderburn, ‘Catalogue of Ruskin’s Drawings’, in The Works of John Ruskin, 1903-1912, Volume 38, pp. 216-309, no.1825 as ‘Casa Foscari:— Window (1845); w. c. Mrs. Cunliffe. Etched in 8, Pl. 8. Ref., 8, 94, 132, 166.’

Exh. Abbot Hall 1969 no.88 as Window in Casa Foscari, Venice, 1845, lent by Guy Barton.

Ruskin Newsletter, no.25, Autumn 1981, p.11 as no.7 as ‘Venice – Window in the Casa Foscari’.

Commentary:

This study is devoted to a single window of the Ca’ Foscari in Venice. More specifically, it is devoted to the window on the second floor (third storey) of the Grand Canal frontage immediately to the left of the balcony.

In the context, this might well seem like a remarkably abstruse approach to the site. Ca’ Foscari is a grand Gothic palace built in 1452 by Doge Francesco Foscari on the lower bend of the Grand Canal, closing the view from the Rialto Bridge down the grandest stretch of water in the whole city.

Photograph: David Hill (2008)

The palace was one of Ruskin’s principal subjects during his visit of 1845 and he devoted several days to its study. This is one of a series of studies that he made at this time and one of the most beautiful and interesting. On this visit he first awoke to the urgency of recording the Byzantine and Gothic remains of Venice before the hand of the restorer or the simple work of time destroyed the original fabric.

Architectural study was not principal purpose of Ruskin’s continental tour of 1845. He spent a long summer studying art for the second volume of Modern Painters. The first volume had been published in 1843, and made him conscious that his art-historical knowledge and experience was lacking. So he committed himself to a taxing itinerary through the major art centres of Italy and arrived in Venice as the finale to study the great Venetian painters of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. He accumulated insight, information and perspective on the tour– and a good deal this duly found its way into the second volume of Modern Painters published in 1846, but he also learned a very great deal about the complexities of ways in which artistic representation could relate to reality. He determined to dedicate his own practice to investigative analysis and understanding. The lessons that he abstracted from that practice were to inform later volumes of Modern Painters. Alongside that, however, following the discoveries that he made in Venice this year, he devoted himself to architecture. The first result of that was his book Seven Lamps of Architecture published in 1849, and that served as a platform from which to launch himself into an intense study of Venice culminating in the three volumes of The Stones of Venice, published 1849-53.

Ruskin explored Venice in 1845 in the company of the artist James Duffield Harding. Ruskin had taken lessons from him in the 1840s, and fashioned his early style in watercolour largely on Harding’s example. They met up on 24 August whilst Ruskin was enjoying a break amongst the mountains of Lago Maggiore (see #1 Isola di Dan Giovanni) and together they travelled on to Venice, arriving on 10 September. Ruskin put up at the Hotel de l’Europe overlooking the Grand Canal, and stayed until 14 October, sketching regularly with Harding.

The tour of 1845 is exceptionally well documented in a series of letters to his father. These were edited and published by Harold Shapiro in Ruskin in Italy, Letters to his Parents, 1845 (1972). Through these we can see that Ruskin’s artistic endeavours in 1845 opened up quite a number of deep issues for the direction of his own practice. Now in his mid-twenties, he began to find himself at odds with much established practice. Through his own extended exercises, he came to see drawing as a process of enquiry, always demanding, often difficult, sometimes soul-destroying, but always driven by the promise of substantive insight, even revelation. One immediate consequence of this was that he realised that most artists – Harding included – fell far short of his own emerging standards of enquiry. In a letter written from Baveno a couple of days after Harding had arrived, he wrote:

I am very glad to have Harding with me & we are going to Venice together – but I am in a curious position with him, being actually writing criticisms on his works for publication, whilst I dare not say the same things openly to his face – not because I would not, but because he does not like the blame, & it does him no good. Yet on my side, it discourages me a little, for Harding does pretty things, such desirable things to have, such pleasant things to show, that when I looked at my portfolio afterwards, & saw the poor result of the immense time I have spent, the brown, laboured, melancholy, uncovetable things that I have struggled through, it vexed me mightily, and yet I am sure I am on a road that leads higher than his, but it is infernally steep, & one stumbles on it perpetually. I beat him dead however at a sketch of a sky this afternoon – there is one essential difference between us. His sketches are always pretty because he balances their parts together & considers them as pictures – mine are always ugly, for I consider my sketch only as a written note of certain facts, & those I put down in the rudest and clearest way as many as possible. Hence, my habits of copying are much more accurate than his, & when, as this afternoon, there is anything to be done which is not arrangeable nor manageable, I shall beat him, but when I looked over my sketches last night – I am afraid you will be sadly, sadly disappointed. I am going to try, now, to get a few a little more agreeable and less full of struggle and effort (note 1).

The letters from Venice show that his resolve to do something more ‘artistic’ was quickly sidelined by the impact that Venice made upon him. He had made two previous visits with his parents, the first in 1835 when he was sixteen, and the most recent in 1841. Now it seemed as if a millennium had passed, and that the golden age of youth had given way to an age of strife, venality, and almost universal blindness to the perception of anything fine or good. The dominating themes of his mature career burst upon him almost whole as he sailed out onto the lagoon from Mestre and saw the new railway bridge to the mainland looking for all the world like the Greenwich railway cutting through south London; ‘only with less arches and more dead wall, entirely cutting off the whole open sea & half the city, which now looks as nearly as possible like Liverpool at the end of the dockyard wall.’ As he passed under the Rialto Bridge he was aghast to discover ‘Birmingham-fashion’ gas lamps illuminating the Grand Canal up to the Foscari Palace. He realised quickly that Venice was in a period of significant change and modernisation, and he feared for the prelapsarian world he remembered.

On the 11th he noted that ‘The Foscari is all but a total ruin – the rents in the walls are half a foot wide’ but at least that was better than the botched restoration work that was going on at the Ca d’Oro, the Doges’ Palace or at St Mark’s. Almost setting aside his intended work on the Venetian artists, he set to work to record as much of the disappearing fabric as he could in the brief time he could squeeze out of this visit. He made a priority of the Ca Foscari, it being as yet untouched by the restorers.

Poor Harding can hardly have known what hit him. Ruskin rose at 4.30 a.m., so as to be at work at 5.30, commandeering gondoliers to their sole service. On the 16th he forewarned his father that he should need more money for it was expensive work. On the 17th he remarked that he and Harding were progressing well with their work at Ca’ Foscari but he was already aware that Harding was not as wedded as he to the study of particulars:

Harding & I shall do the Foscari pretty well between us. I have got the architecture – mouldings, capitals & all. I began it small. Harding said I should frighten the Daguerreotype into fits, and Coutet (note 2) said ‘Ca ne le resemble pas, c’est la meme chose.’ I found it impossible however to accomplish it so completely, and I am therefore taking large studies of the most interesting parts, leaving the rest to sketch in lightly.

Ruskin’s obsession with finding out his subject developed into a condition of some eccentricity, as he admitted on the 20th September: ‘The outside drawing takes me a terrible time, for it is no use to me unless I have it right out & know all about it. I have gone so far as to gather and draw the weeds that grow on the old Foscari.’

Harding left on the 24th September, but before doing so made a present to Ruskin of a drawing of the Ca’ Foscari. It is something of a frustration that this cannot now be traced. Ruskin worked desperately on, thinking himself in a race against time, but by the 1 October he began to realise the impossibility of realising his artistic ideal:

I am thoroughly thrown on my back with the Palazzo Foscari – don’t know what the deuce to do with it. I have all its measures and mouldings & that is something, but I can’t get on with the general view. I began it as it should be done, taking plenty time.. But this wouldn’t do at all. I should have taken a month to do it & now I can find no expedient nor mode of getting at it that will give me what I want. To take the outline is what has been done a thousand times – the beauty of it is in the cracks and the stains, and to draw these out is impossible and I am in despair….I see things about five times as beautiful as I used to do, and as I can’t draw much better, I am reduced to knocking my fists together and moaning. I shall come away soon now I think. – it’s no use stopping.’

On the 4th October he reflected: ‘I suppose… [I am] trying to do too much, & yet it is just this too much that I want, for as to taking common loose sketches in a hackneyed place like Venice, it is utter folly. One wants just what other artists have not done, & what I am as yet nearly unable to do.’ It is perhaps unfortunate that he could not see that he really was achieving something significant in the area that others had not., but yet the phrase ‘near unable’ is interesting for it suggests that he felt himself close.

He left on 14 October, feeling better about his accomplishments. The weather was fine during his last two weeks, and he remedied the problem of not getting down the general view of his subjects by buying a quantity of daguerreotypes. This photographic process was very new. It had been first patented in 1839, and specialists began to popularise the medium from about 1842. Not that the early exponents all made fortunes. Quite the reverse, as we hear in Ruskin’s report of 7th October:

I have been lucky enough to get from a poor Frenchman here, said to be in distress, some most beautiful, though small, Daguerreotypes of the palaces I have been trying to draw – and certainly Daguerreotypes taken by this vivid sunlight are glorious things. It is very nearly the same as carrying off the palace itself – every chip of stone & stain is there – and, of course, there is no mistake about proportions. I am very much delighted with these and am going to have some more made of pet bits. It is a noble invention, say what they will of it, and any one who has worked and blundered and stammered as I have for four days, and then sees the thing he has been trying to do so long in vain, done perfectly & faultlessly in half a minute, won’t abuse it afterwards.’

One of Ruskin’s daguerreotypes of Ca Foscari survives in the collection of Ken and Jenny Jacobson. I have not been able to see it yet, but it is to be included in a forthcoming book by them that will provide a comprehensive treatment of Ruskin’s collection of daguerreotypes. This is due to be published later this year, and I hope to be able to include an illustration here, and to consider the relationship with the drawing, after the book has been published (note 3).

Picking through the references to Ca’ Foscari in the letters, it is clear that Ruskin compiled a systematic series of studies of details, besides at least one attempt at the whole. The present is drawing is inscribed ‘No.3’, but only one other numbered example is known, No.4, at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (note 4), which records a fourth storey window with weeds growing on its lower sill. That watercolour is included in this year’s John Ruskin: Artist and Observer exhibition (note 5, and see article no.1, introduction) and is reproduced in colour. It is the very epitome of Ruskin falling in love with the cracks and stains, though perhaps located in a more conventional tradition of the picturesque than the present drawing. Numbers ‘1’ and ‘2’ have never been noted, nor, indeed any number ‘5’ or higher.

Cook and Wedderburn recorded several Ca Foscari subjects in their catalogue of works by Ruskin in the Library Edition of the Works of John Ruskin (Vol.38, p.293):

Casa Foscari:—

Casa Foscari (1845); w. c. (14 x 17½). South Kensington Museum. [1818]

Inscribed: “Ca Foscari, No. 4, Sept. 1845.” For a ref. to R.’s drawing the Palace in company with Harding, see 8, 131 n.

Casa Foscari and the Frari (1876); pencil and tint (20 x 13). Mrs. Cunliffe. Exh.—Coniston 197, R.W.S. 109, M. 96. [1819]

“R.’s note on the drawing is ‘left off beaten.’ He generally knew when to leave off, and what to leave out. Of one of his best Venetian drawings, he often said, ‘What a nice sketch it would have been if— had not persuaded me to put in a sky!’ And here enough is given to show the great mass of building in difficult perspective effect. The gondola was separately studied in a coloured drawing—so much time and trouble was spent over the work.”—Manchester Catal.

Balcony: detail drawing; wash. Exh.—M. 249. [1820]

Capitals of third story (Sept. 1845); wash (14 x 8). Brantwood. Exh.—R. W. S. 237, F.A.S. 141. [1821]

Detail drawing; pencil and white. Exh.—M. 242. [1822]

Detail drawing; wash. Exh.—M. 292. [1823]

Study of living foliage (Sept. 19, 1845); w. c. (9¾ x 14½). S. C. Cockerell. [1824]

Window (1845); w. c. Mrs. Cunliffe. Etched in 8, Pl. 8. Ref., 8, 94, 132, 166. [1825]

Details of Window. Etched in 8, Pl. 4, fig. 8. [1826]

Sadly, very few of these can be identified today. The present drawing is no.1825, at this time in the collection of Robert Cunliffe’s widow, he having died in 1902. The V&A drawing is no. 1818. Quite where the remaining material might be is unclear. There is at least one study of Ca’ Foscari in Ruskin’s notebooks for the 1845 tour, which survive at the Ruskin Library at the University of Lancaster (note 6). This is a study of the interior of the river court – now the reception area of the University of Venice – and is reproduced in The Diaries of John Ruskin, 1956, volume 1, pl.19. This shows the building reduced to less exalted purposes, filled with miscellaneous timbers and fragments of masonry, and its windows closed with crude shuttering. I have not yet had chance to work through whatever other drawings of Ca’ Foscari (if any) the notebooks might contain, but I hope to do that on my next visit to the Ruskin Library, and will report any discoveries here. Of the things listed by Cook and Wedderburn that one might most like to find is the ‘Study of Living foliage’ then in the collection of S.C.Cockerell. Ruskin mentioned this in a letter to his father of 20 September and it would be nice to be able to exemplify his eccentricity.

Ruskin described the subject of the main drawing as ‘one of the lateral windows of the third storey of the Palazzo Foscari. It was drawn from the opposite side of the Grand Canal, and the lines of its traceries are therefore given as they appear in somewhat distant effect’ (note 7). Despite Ruskin’s sense of being limited to only the distant effect, his observations appear remarkably specific. The Grand Canal frontage of the Ca’ Foscari faces just a little north of east so the sun goes round to the left and rakes across it towards noon as seen here before moving round to plunge the front into indirect light. Ruskin has taken elaborate care to record the way in which the light, high to the left, picks out the detail. He even notices that a large chunk has fallen away from the right hand part of the ogee and that the stone surface is pitted and corroded in places so as not to reflect the light fully.

detail of damaged masonry

Photograph: David Hill

By courtesy of the Master of King’s College, Cambridge

He records missing pieces of moulding and chips and cracks all over (note 8). He also remarked that the glazing was generally set deep behind the tracery so as not to interfere with the clarity with which the traceries articulated the division of light and dark (note 9). In this case the shutters in the upper part of the window are open – that to the right reflects the sky, and below the drapes flap out of the opening. The lower part is glazed and the casement closed, so that the glass reflects blue, in contrast to the lamp black and brown space of the interior as above.

Detail of glazing

Photograph: David Hill

By courtesy of the Master of King’s College, Cambridge

For someone situated at the far side of the canal this is sharp observation, but perhaps his identification of the viewpoint, and the implied constraint of a ‘somewhat distant effect’ is intended to signal the necessity of overcoming the limitations of such a situation (note 10). The other drawings on the sheet record a closer examination of the fabric. At the bottom right is a close study of the carved foliage of one of its capitals.

Detail of left capital

Photograph: David Hill

By courtesy of the Master of King’s College, Cambridge

Specifically this can be identified as that of the left-hand shaft of the window. This is established by the viewpoint which is quite close and below to the right. The only practical vantage point is the balcony of the central range of windows on that storey. The sheet also contains sections of the mouldings at the top right through two points in the tracery of the upper window and below that through the moulding just above the capital. Above the drawing of the capital Ruskin also made a separate detailed study of the light as it picked out the details of the moulding, and later expressed the opinion that that it was the grandest moulding to catch the light in of any that he had found in Venice (note 11).

Detail of the sections of mouldings

Photograph: David Hill

By courtesy of the Master of King’s College, Cambridge

Finally he realised that even his detailed study of the capital failed to register the finest part of the detail. In reviewing his treatment of the rope twist carving on the return below the capital he noticed that his treatment, albeit taken from a close viewpoint, was still merely generic. As he remarked in a letter to his father on 14 September, St Mark’s had a good deal of very fine rope-twist carving, made and given educated form by a maritime culture. He took pains in this study to record its form in sufficient detail to articulate properly the sensibility that informed it: ‘Cable thus not as a n’.

Detail of rope-twist carving

Photograph: David Hill

By courtesy of the Master of King’s College, Cambridge

It is hard to imagine many of today’s visitors to Venice being interested in such arcana. Ruskin’s belief, however, was that such attention is important. The medieval builders and masons demonstrated it and founded their whole aesthetic on it. The Renaissance, he came to believe, replaced that with mensuration and mechanical modes of production, and his own age age (perhaps even more so our own) languished in insentience. As he further remarked to his father on 14 September: ‘the modern work (note 12) has set its plague spot everywhere – the moment you begin to feel, some gaspipe business forces itself on the eye, and you are thrust into the 19th century.’

After completing the second volume of Modern Painters in 1846 Ruskin conceived a larger plan to make a similar impact in the field of architecture as he had in the field of art. After all, he could see plainly that public awareness in architecture was equally requiring of some development, if not rebuilding from the ground up. In many ways the present drawing represents the point of discovery of this new mission, and it is perhaps significant that in the first published product, Seven Lamps of Architecture, 1849, Ruskin chose to include an engraving of this sketch as one of its key illustrations. It is not, after all as if the window figures large as a subject in the text. On the contrary, Ruskin has only one or two direct comments to make. It is more that the image itself functioned as powerful testimony to the intensity of scrutiny that he was advocating, the closeness of his material observation, and the informed and educated frame that rendered such stuff vital and instinct with significance.

Window in the Ca’ Foscari, Venice

Softground etching by John Ruskin published in the first edition of Seven Lamps of Architecture, 1849.

Photograph: David Hill

Ruskin was surprisingly diffident about the illustrations for Seven Lamps. This despite the fact that he personally engraved the images in softground, the etching medium that most directly transmits the quality of the hand at work in making the image. The prints from these plates only ever appeared in the first edition, and despite the fact that they are the most vivaciously drawn and considered etchings of his whole career, he did not have the confidence in them that they deserved. In the Preface to Seven Lamps he admitted:

Every apology is, however, due to the reader for the hasty and imperfect execution of the plates. Having much more serious work in hand, and desiring merely to render them illustrative of my meaning, I have sometimes very completely failed even of that humble aim; and the text, being generally written before the illustration was completed, sometimes naïvely describes as sublime or beautiful, features which the plate represents by a blot. I shall be grateful if the reader will in such cases refer the expressions of praise to the Architecture, and not to the illustration. § 3. So far, however, as their coarseness and rudeness admit, the plates are valuable; being either copies of memoranda made upon the spot. For the accuracy of the rest I can answer, even to the cracks in the stones, and the number of them; and though the looseness of the drawing, and the picturesque character which is necessarily given by an endeavour to draw old buildings as they actually appear, may perhaps diminish their credit for architectural veracity, they will do so unjustly (note 13).

Even in his diffidence there is, however, a certain firmness of resolve. It is fortunate on the whole that in his general practice he allowed himself to be led by his sense of purpose, rather than by the dictates of consensus and established value. At least the reviewer in The Guardian (6 June 1849), could see the value in what Ruskin was doing:

Though only rough sketches, not always so complete as to be entirely clear, they are executed with masterly boldness, and we doubt not, where that is aimed at, masterly accuracy. No one can look at them, at any rate, the second time, without seeing in them what power and life the sketch of a detail may manifest, and learning, in the purity of their roughest, and the decision and sureness of their wildest, lines, the difference between the rudeness of power and perfect knowledge, and the rudeness of confusion and incapacity (note 14).

In this case his resolve was frustrated in part by technicalities. The soft copperplates were exhausted by the first edition, so when it came to the second edition published in 1855 Ruskin had the plates professionally re-engraved on steel by the very R.P.Cuff. The new versions do not quite have the same sense of life of Ruskin’s originals, nor the personal acquaintance or identification with the material. In the Preface to the second edition Ruskin said:

I have only to add that the plates of the present volume have been carefully re-etched by Mr. Cuff, retaining, as far as possible, the appearance of the original sketches, but remedying the defects which resulted in the first edition from my careless etching (note 15).

The defects in question were by and large matters of numbering and labelling. The key matters of style and aesthetic form were retained.

The drawing and its engraving together constitute almost a manifesto of principles that Ruskin was to elaborate over his remaining career. One final attribute of pre-Renaissance art that he found particularly beguiling, and which he was to dwell upon in later writing, particularly in Stones of Venice, was that of irregularity. We can see here that he has drawn a circle at the top right, as part of the construction of his drawing, and also as part of his analysis of the geometric principles underlying the design of the traceries. He remarked on the design of this particular window in The Seven Lamps of Architecture:

It shows only segments of the characteristic quatrefoils of the central windows. I found by measurement their construction exceedingly simple. Four circles are drawn in contact within the large circle. Two tangential lines are then drawn to each opposite pair, enclosing the four circles in a hollow cross. An inner circle struck through the intersections of the circles by the tangents, truncates the cusps (note 16).

Detail of the geometric construction

Photograph: David Hill

By courtesy of the Master of King’s College, Cambridge

What he found particular attractive, however, was that despite there being measure and method the execution was never merely mechanical, so the forms were never quite exact; the forms approximated as well as human care desired. As he argued in Stones of Venice, the Renaissance imposed a precision and uniformity that stripped affect from the handiwork. The drawing is an enactment of the same human engagement. It is frankly the product of hand and eye. Furthermore this required real imaginative engagement. Though detail might have been recorded more expeditiously by the new daguerreotype process, its detail was unfiltered through living perception nor mediated through the potentially fallible hand. As he later came to realise and discuss (note 17), the comparison of drawing and photography serves in the end to clarify the former’s unique ability to mediate quality of mind in the very act of it attempting to apprehend quality of form. In retrospect thus, we may see in this drawing one of the more important catalysing exercised of his early career.

Notes and acknowledgements:

I am am grateful to Ken Jacobson and Professor Stephen Wildman for reading the first incarnation of this article and suggesting improvements.

1 H. Shapiro, Ruskin in Italy, Letters to his Parents, 1845, 1972, no.115 written from Baveno, 26 August, 1845, pp. 189-90. Subsequent references to letters are given by the date only.

2 Joseph Marie Couttet. A very experienced Alpine guide from Chamonix who served as a sort of equerry to Ruskin on his continental tours. He was a seriously accomplished Alpinist, and rather like a fish out of water in Venice. We shall hear more of him once back amongst the mountains with other examples from the King’s College collection.

3 The Jacobson collection of Ruskin’s daguerreotypes comprises 188 examples. For a link to their website click the following and then press your browser’s ‘back’ button to return to this page: http://www.jacobsonphoto.com/news/viewnews.html?id=26. A few examples from the Jacobson collection are included in the 2014 exhibition John Ruskin: Artist and Observer at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, and afterwards at the National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh. The Ruskin Library at the University of Lancaster has a further 125 examples a selection of which are included in the 2014 exhibition: John Ruskin – Photographer and Draughtsman at the Watts Gallery, Compton, near Guildford. Professor Stephen Wildman curated a series of exhibitions at Lancaster of the Ruskin Library collection, focusing on Tuscany in 2010, France in 2011, Switzerland in 2012, and finally Venice and Verona in 2013.

4 A window in the Foscari Palace, Venice, 1845, pencil and watercolour on paper, Height: 46.6 cm, Width: 31.6 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, D.1726-1908. To see the watercolour in the V&A’s own online catalogue click the following link and then press your browser’s ‘back’ button to return to this page: http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O78112/watercolour-ruskin-john/.

5 This is included in the John Ruskin: Artist and Observer exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada, 2014 as exhibit number 3.

6 Ruskin’s notebooks of 1845 are MSS 5a and 5b at the Ruskin Library, University of Lancaster.

7 Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) in Cook and Wedderburn (eds.) Works of John Ruskin, 1903-12, Vol.8, p. 131.

8 It is instructive to compare the watercolour with his engraving, for the latter considerably clarifies the exact blemishes being noted.

9 Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) in Cook and Wedderburn (eds.) Works of John Ruskin, 1903-12, Vol.8, p. 132.

10 The issue of how things may be represented when seen at a distance came to exercise Ruskin at length. The matter was brought to a head by a later drawing in the King’s College group, The Buttress of an Alp at Martigny, which will be treated in article five in this series.

11 Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) in Cook and Wedderburn (eds.) Works of John Ruskin, 1903-12, Vol.8, p. 166.

12 This is as given by Shapiro 1972, p.201, but perhaps the word ‘work’ is a misreading of ‘world’?

13 Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849), p. vi; in Cook and Wedderburn (eds.) Works of John Ruskin, 1903-12, Vol.8, p. 4.

14 Quoted in in Cook and Wedderburn (eds.) Works of John Ruskin, 1903-12, Vol.8, p. xlv.

15 Cook and Wedderburn (eds.) Works of John Ruskin, 1903-12, Vol.8, p. 14.

16 Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849), p. 203; in Cook and Wedderburn (eds.) Works of John Ruskin, 1903-12, Vol.8, p. 131.

17 An excellent introduction to this topic is given by Michael Harvey, ‘Ruskin and Photography’, in Oxford Art Journal , Vol. 7, No. 2, (1984) , pp. 25-33 , published by: Oxford University Press and available online through JSTOR at URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1360290.

Hello colleagues, its wonderful article on the topic of cultureand fully explained,

keep it up all the time.