This article visits the famous ‘Ruskin’s View’ at Kirkby Lonsdale in Cumbria. It is so christened after a particularly purple description of the scenery by Ruskin. Hardly anyone, however, has ever considered his commentary in full. In what follows we will retrace Ruskin’s footsteps and discover that he said rather more than is generally admitted.

Photograph by David Hill, taken 12 May 2009, 11.48 GMT

On a sunny and frosty winter’s morning on 22 January 1875, the famous art critic John Ruskin walked through the churchyard at Kirkby Lonsdale to enjoy the wonderful view over the Lune valley. The site had been sketched by the great artist J.M.W.Turner in 1816, and popularised through an engraved watercolour, but had been celebrated in prose several times before that.

The Lune Valley from Kirkby Lonsdale Churchyard, c.1818

Watercolour, 286 x 415 mm

Private Collection ex Bonhams London 26 January 2012, lot 12 (sold for £217,250)

Image, David Hill. To see the image in Bonhams online catalogue click on the following link, then use your browser’s ‘back’ button to return to this page:

https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/19571/lot/12/

Ruskin knew of the view from the engraving of this watercolour that was published in Turner’s ‘History of Richmondshire’ in 1822, but the view was already feted by others, including William Wordsworth in his Guide to the Lakes published in 1810. It is not clear when it was decided to call it ‘Ruskin’s View’, but it was still known as Turner’s view well into the twentieth century.

Photograph by David Hill taken 12 May 2009, 12.25 GMT

None, however, extolled it quite so effectively as did Ruskin:

“The valley of the Lune at Kirkby is one of the loveliest scenes in England—therefore, in the world. Whatever moorland hill, and sweet river, and English forest foliage can be at their best, is gathered there; and chiefly seen from the steep bank which falls to the stream side from the upper part of the town itself. There, a path leads from the churchyard out of which Turner made his drawing of the valley, along the brow of the wooded bank, to open downs beyond; a little bye footpath on the right descending steeply through the woods to a spring among the rocks of the shore. I do not know in all my own country, still less in France or Italy, a place more naturally divine, or a more priceless possession of true “Holy Land.”

Photograph by David Hill taken 21 March 2016, 15.36 GMT

The passage has been feted by promoters of Kirkby Lonsdale. Despite the fact that the view was thought of by Ruskin as Turner’s, and indeed was known by locals as Turner’s view almost within living memory, the view is now resolutely associated with Ruskin. It is iterated on every signboard in the area. Signposts guide you from all quarters to ‘Ruskin’s View’ and signboards at regular intervals repeat his glowing endorsement. The sentiment is ubiquitous in the tourist promotion of Kirkby Lonsdale, and the following from ‘Explore South Lakeland’ might be taken as representative:

‘Approach the beautiful Norman Church of St Mary the Virgin by a pretty alleyway beside the Sun Inn and linger for a while in its lovely churchyard, especially if the sun is shining – there are plenty of seats. From the far corner of the churchyard, follow the signs to Ruskin’s View where the path opens into Church Brow, a promenade high above the River Lune. There you can feast your eyes on a breathtaking panorama of the Lune Valley and Underley Hall – the famous, heavenly Ruskin’s View.

http://www.exploresouthlakeland.co.uk/hidden-gems/item/14/Ruskin-s-View–Kirkby-Lonsdale/

[Click on image to enlarge]

Photograph by David Hill, taken 25 March 2016, 11.05 GMT

Ruskin made his comment in the fifty-second of a series of monthly ‘Letters to the Workmen of England’ published in April 1875 and collected in the fifth annual volume of ‘Fors Clavigera’ [FORS CLAVIGERA: VOL. V, LETTER 52 (APRIL 1875), ‘Vale of Lune’, pp. 92-99; Works XXVIII, 298-304]. As a whole, the complete eight volumes are not an easy read, but they do contain a thorough critique of the political and spiritual state of British society in the later nineteenth century. Much of what he has to say seems as topical today as it did then, and before Christmas I got round to a retirement project to read it in its entirety. Arriving at the familiar passage on Kirkby Lonsdale, I was more than a little surprised to see the full context in which it was set.

Ruskin’s comment was made to emphasise the beauty endowed to the site by nature, but as a pointed contrast to the folly, filth, and impoverishment of spirit of the contemporary works. At the risk of my being barred entry to Kirkby Lonsdale for evermore, I think we need to hear what Ruskin really said about that view.

[Click on any image to enlarge]

“I have been driving by the old road from Coniston here, through Kirkby Lonsdale, and have seen more ghastly signs of modern temper than I yet had believed possible.

“The valley of the Lune at Kirkby is one of the loveliest scenes in England—therefore, in the world. Whatever moorland hill, and sweet river, and English forest foliage can be at their best, is gathered there; and chiefly seen from the steep bank which falls to the stream side from the upper part of the town itself. There, a path leads from the churchyard out of which Turner made his drawing of the valley, along the brow of the wooded bank, to open downs beyond; a little bye footpath on the right descending steeply through the woods to a spring among the rocks of the shore. I do not know in all my own country, still less in France or Italy, a place more naturally divine, or a more priceless possession of true “Holy Land.”

[Click on any image to enlarge in a gallery, and to see captions]

“Well, the population of Kirkby cannot, it appears, in consequence of their recent civilization, any more walk, in summer afternoons, along the brow of this bank, without a fence. I at first fancied this was because they were usually unable to take care of themselves at that period of the day: but saw presently I must be mistaken in that conjecture, because the fence they have put up requires far more sober minds for safe dealing with it than ever the bank did; being of thin, strong, and finely sharpened skewers, on which if a drunken man rolled heavily, he would assuredly be impaled at the armpit. They have carried this lovely decoration down on both sides of the woodpath to the spring, with warning notice on ticket,—“This path leads only to the Ladies’ well—all trespassers will be prosecuted”—and the iron rails leave so narrow footing that I myself scarcely ventured to go down,—the morning being frosty, and the path slippery,—lest I should fall on the spikes. The well at the bottom was choked up and defaced, though ironed all round, so as to look like the “pound” of old days for strayed cattle: they had been felling the trees too; and the old wood had protested against the fence in its own way, with its last root and branch,—for the falling trunks had crashed through the iron grating in all directions, and left it in already rusty and unseemly rags, like the last refuse of a railroad accident, beaten down among the dead leaves.

[Click on any image to enlarge in a gallery, and to see captions]

“Just at the dividing of the two paths, the improving mob [* I include in my general term “mob,” lords, squires, clergy, parish beadles, and all other states and conditions of men concerned in the proceedings described] of Kirkby had got two seats put for themselves—to admire the prospect from, forsooth. And these seats were to be artistic, if Minerva were propitious,—in the style of Kensington. So they are supported on iron legs, representing each, as far as any rational conjecture can extend—the Devil’s tail pulled off, with a goose’s head stuck on the wrong end of it. Thus: and what is more—two of the geese-heads are without eyes (I stooped down under the seat and rubbed the frost off them to make sure), and the whole symbol is perfect, therefore,—as typical of our English populace, fashionable and other, which seats itself to admire prospects, in the present day.

[Click on any image to enlarge in a gallery, and to see captions]

“Now, not a hundred paces from these seats there is a fine old church, with Norman door, and lancet east windows, and so on; and this, of course, has been duly patched, botched, plastered, and primmed up; and is kept as tidy as a new pin. For your English clergyman keeps his own stage properties, nowadays, as carefully as a poor actress her silk stockings. Well, all that, of course, is very fine; but, actually, the people go through the churchyard to the path on the hill-brow, making the new iron railing an excuse to pitch their dust-heaps, and whatever of worse they have to get rid of, crockery and the rest,—down over the fence among the primroses and violets to the river,—and the whole blessed shore underneath, rough sandstone rock throwing the deep water off into eddies among shingle, is one waste of filth, town-drainage, broken saucepans, tannin, and mill-refuse.

[Click on any image to open in gallery, and see captions]

[…some comment on Clapham and Bolton Abbey omitted here]

“Very certainly, nevertheless, the young ladies of Luneside and Wharfedale don’t pant in the least after their waterbrooks; and this is the saddest part of the business to me. Pollution of rivers!—yes, that is to be considered also;—but pollution of young ladies’ minds to the point of never caring to scramble by a riverside, so long as they can have their church-curate and his altar-cloths to their fancy—this is the horrible thing, in my own wild way of thinking. That shingle of the Lune, under Kirkby, reminded me, as if it had been yesterday, of a summer evening by a sweeter shore still: the edge of the North Inch of Perth, where the Tay is wide, just below Scone; and the snowy quartz pebbles decline in long banks under the ripples of the dark clear stream.

“My Scotch cousin Jessie, eight years old, and I, ten years old, and my Croydon cousin, Bridget, a slim girl of fourteen, were all wading together, here and there; and of course getting into deep water as far as we could,—my father and mother and aunt watching us,—till at last, Bridget, having the longest legs, and, taking after her mother, the shortest conscience,—got in so far and with her petticoats so high, that the old people were obliged to call to her, though hardly able to call, for laughing; and I recollect staring at them, and wondering what they were laughing at. But alas, by Lune shore, now, there are no pretty girls to be seen holding their petticoats up. Nothing but old saucepans and tannin—or worse—as signs of modern civilization.

Photograph by David Hill, taken 12 May 2009, 14.40 GMT

“But how fine it is to have iron skewers for our fences; and no trespassing (except by lords of the manor on poor men’s ground), and pretty legs exhibited where they can be so without impropriety, and with due advertisement to the public beforehand; and iron legs to our chairs, also, in the style of Kensington!” Doubtless; but considering that Kensington is a school of natural Science as well as Art, it seems to me that these Kirkby representations of the Ophidia are slightly vague. Perhaps, however, in conveying that tenderly sagacious expression into his serpent’s head, and burnishing so acutely the brandished sting in his tail, the Kirkby artist has been under the theological instructions of the careful Minister who has had his church restored so prettily;—only then the Minister himself must have been, without knowing it, under the directions of another person, who had an intimate interest in the matter. For there is more than failure of natural history in this clumsy hardware. It is indeed a matter of course that it should be clumsy, for the English have always been a dull nation in decorative art: and I find, on looking at things here afresh after long work in Italy, that our most elaborate English sepulchral work, as the Cokayne tombs at Ashbourne and the Dudley tombs at Warwick (not to speak of Queen Elizabeth’s in Westminister!) are yet, compared to Italian sculpture of the same date, no less barbarous than these goose heads of Kirkby would appear beside an asp head of Milan. But the tombs of Ashbourne or Warwick are honest, though blundering, efforts to imitate what was really felt to be beautiful; whereas the serpents of Kirkby are ordered and shaped by the “least erected spirit that fell,” in the very likeness of himself!

“For observe the method and circumstance of their manufacture. You dig a pit for ironstone, and heap a mass of refuse on fruitful land; you blacken your God-given sky, and consume your God-given fuel, to melt the iron; you bind your labourer to the Egyptian toil of its castings and forgings; then, to refine his mind you send him to study Raphael at Kensington; and with all this cost, filth, time, and misery, you at last produce—the devil’s tail for your sustenance, instead of an honest three-legged stool.

“You do all this that men may live—think you? Alas—no; the real motive of it all is that the fashionable manufacturer may live in a palace, getting his fifty per cent. commission on the work which he has taken out of the hands of the old village carpenter, who would have cut two stumps of oak in two minutes out of the copse, which would have carried your bench and you triumphantly,—to the end of both your times.”

Photograph by David Hill, taken 25 March 2016, 10.48 GMT

“..with a goose’s head stuck on the wrong end of it..”

POSTSCRIPT

This article started out as a bit of a wild goose chase. I quickly discovered from photographs taken on previous visits that Ruskin’s benches had disappeared from their original setting. However it was clear that the railings survived in serried spears and so thought it worth the risk to trace Ruskin’s footsteps nonetheless. And it was pleasant enough this March to wander in the churchyard, test one’s fingers on the railings, pick one’s way down the path to the Ladies’ Well, fail to find the old spring, search municipal gardens and spaces for Ruskin’s benches; wonder whether they might be secreted in some private garden, and come away disappointed thinking that they must have been melted down for scrap.

So driving away up the A65 it was a shock to suddenly see them sitting forlorn at the side of the main road. And I doubt anyone has been so gladdened to see them. Few since Ruskin can have been seen kneeling on the floor to see whether the heads do indeed lack eyes. Ruskin would probably have thought it grimly appropriate that what eyes there are look out now only upon wheels scuttering by, and are covered not in frost but in road grit.

Photograph by David Hill, 25 March 2016, 10.51 GMT

They stand today by the side of the A65 near its junction with Main Street. It’s not quite the view to which they had grown accustomed.

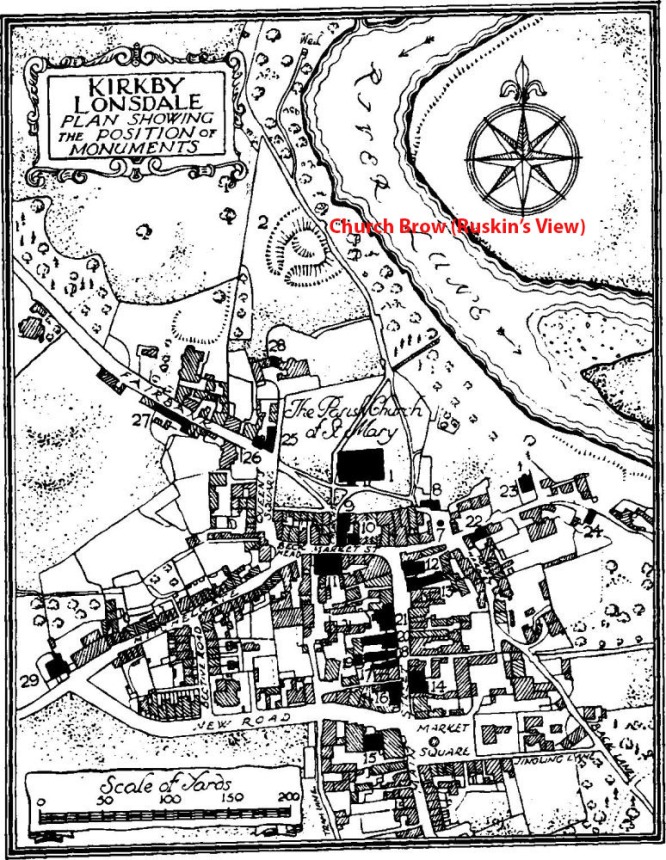

Placemarks indicate the principal sites discussed in the article.

[Best viewed full size; click on image to enlarge]

Still it seems against all odds that they do survive; albeit rather battered and bruised. Three of the four castings have lost their tails, and the quality (although Ruskin might have harrumped at the word) of the detail has degraded through rust and successive repaintings.

So what to do? Maybe put them back? Certainly Ruskin’s description and illustration seems to qualify them as museum-quality objects. And it does seem a shame that they have been removed from what is otherwise a high-grade survival of the environment that he described. They aren’t perhaps as sturdy as they once were, but there might well be a case for restoring them to the Church Brow, somewhere. The entrance to the new graveyard is very near their original situation. Ruskin would certainly oppose any notion of restoration; but preservation he might not oppose. After all his meditation on the site was intended to render urgent the capacity to fully appreciate its beauty and to provoke constant struggle against the erosion of that appreciation. That threat is as relevant today as it was then. Kirkby Lonsdale is truly a great place to have one’s eyes open.

Photograph by David Hill, taken 25 March 2016, 11.30 GMT

PPS.

I cannot close this without referring the reader to the work of Paul Dobraszczyk. He is a photographer, artist and cultural commentator specialising in the built environment. He has a wonderful website at

http://ragpickinghistory.co.uk/

His recent book, Iron, Ornament and Architecture in Victorian Britain: Myth and Modernity, Excess and Enchantment (Ashgate, 2014), begins by thinking about Ruskin’s benches at Kirkby Lonsdale, though he does not seem to have known that they survived. He points out that this style of bench is very widespread, and they can be found the length and breadth of Britain. Dobraszczyk makes the point that it was probably their very municipal proliferation that galled Ruskin so much. Indeed companies still manufacture to the pattern. It is the officially adopted style of park bench in Harrogate and Knaresborough. Still, none received quite such a critical sandblasting as the two at Kirkby Lonsdale.

Just found this! Thanks for the clarification here on the benches – I didn’t know they survived, or their precise location. Many thanks!

What a great article, I really enjoyed reading about the salty context for Ruskin’s enthusiasm about the view!

This is a fascinating piece, and am glad you set yourself that task of reading Ruskin to bring this to us.

My first thought, prior to reading the article and having seen only the photo by David Hill, was ‘what a lovely place, shame about the railings’, presuming them to have been erected relatively recently. Heartening, I suppose, to find one is in tune with Ruskin. However, it is his identification of ‘health and safety’ as an excuse to ruin the innocent – and those less so – joys of scrabbling along the brow that is perhaps most startling. We sinned then as we sin now, it seems