Ancient Greek marble well-head recorded at Corinth in 1805 and subsequently lost, until recognised at Bretton Hall, Yorkshire, in 1993.

Photograph by David Hill, taken July 1993

This is the first of an intended series of articles that relates the discovery of two important Greek antiquities at Bretton Hall and explores their context and origins.

Ancient Greek carved altar, made on the island of Delos, recognised at Bretton Hall, Yorkshire, 1991

Photograph by David Hill, taken July 1993

I has taken me twenty-five years to get round to telling this story. I became involved in 1991 when I realised that one piece was an altar made in the second century BC on the Greek island of Delos. The other was a marble well-head carved with a frieze of ten figures that turned out to be famous but lost to scholarship for the best part of two hundred years.

Photograph by David Hill taken 7 May 2007, 13.45 GMT

Not that either piece was at all hidden. I walked past them every day for nine years before waking up to their potential significance. They were sited in the grounds of Bretton Hall College, near Wakefield in Yorkshire where I landed my first full-time lecturing job in 1982. This was a specialist college of education and practice-based arts, affiliated to the University of Leeds, and the home of the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. The pieces could hardly have been set in a more visually alert environment.

The altar stood outside the refectory, where a rectangular recess in its flat top served as an ashtray.

Photograph by Derek Linstrum

Image courtesy of York Digital Library: The University of York

To see this image amongst Derek Linstrum’s collection on the York Digital Library website, click on the following link, and use your browser’s ‘back’ button to return to this page:

https://dlib.york.ac.uk/yodl/app/image/detail?id=york%3a845238&ref=browse

Photograph by David Hill, taken at Bretton Hall, July 1993

The well-head stood outside one of the halls of residence, where in winter it served as a litter bin, ideal for empty crisp packets and Martini bottles, and in summer for the gardeners’ French marigolds and geraniums. Never can there have been more perfect example of being hidden in plain view.

Photograph by Derek Linstrum

Image courtesy of York Digital Library: The University of York

To see this image amongst Derek Linstrum’s collection on the York Digital Library website, click on the following link, and use your browser’s ‘back’ button to return to this page:

https://dlib.york.ac.uk/yodl/app/image/detail?id=york%3a846764&ref=browse

Winter service as a litter bin

Photograph by David Hill, taken winter 1993-4

Summer service as a plant pot.

Photograph by David Hill, taken summer 1993.

I had previously worked at Temple Newsam House in Leeds as researcher, so knew a little about country house gardens. Bretton Hall was landscaped by Capability Brown in the eighteenth century, so it seemed a fair assumption that these pieces were of that period, and probably casts or copies of known originals. I liked to teach art history from locally available examples and contended that with a bit of imagination one could illustrate a wide spectrum of art history from prehistory to the present day with examples drawn exclusively from a thirty-mile radius of Wakefield. I encouraged students to research work that was readily accessible. It seemed to me that most art historians only valued things that were in the great collections, and would talk about anything so long as it was a long way away. At least London, but much better Paris, and even better, New York. Several of my undergraduates did genuinely valuable research into things immediately around them.

More than once I thought the Bretton sculptures might be the starting-point for an interesting research journey, but it was only one day whilst rootling about in Leeds Museum that my eyes came to rest on an object that bore more than a passing resemblance to the Bretton ash-tray.

Leeds Museums, Gott Collection (Hicks, no.6

Photograph courtesy of UKEPIGRAPHY, University of Manchester

To see this image in the University of Manchester’s website click on the following link, and use your browser’s ‘back’ button to return to this page:

http://ukepigraphy.humanities.manchester.ac.uk/index.php/CIG_2312:_Marble_Altar

The label read: ‘Circular altar of white marble, from Delos, c.200 B.C, from the Gott Collection.’ It had evidently been purchased by Benjamin Gott whilst travelling in Greece in 1815. Suddenly a penny dropped weighing something like half a ton. So the Bretton ash tray wasn’t made of concrete, it was marble; it was ancient Greek; it came from Delos, and it was three times the size of the Leeds example, and intact, the carving in infinitely better condition. The example in front of me was a wreck; the Bretton piece a serious museum quality antiquity. And if the ashtray was a genuine Greek antiquity, what might the litter bin cum plant pot turn out to be? That was marble that glistered attractively in the light, and had a frieze of classical figures parading around its drum. It could be important. I was startled into attention as if the altar had dropped on my toe.

So I made a hasty visit to the British Museum that September before teaching started. I looked at their altars and saw sufficient classical Greek sculpture to convince me of the antiquity and importance of the Bretton pieces. Shortly afterwards I sent enquiries to Leeds Museum, and the British Museum and the keepers sent me sufficient references to keep me engrossed for some time.

From a research point of view this was all an embarrassment of riches. I was finishing Turner in the Alps, which came out in 1992, and working on Turner on the Thames which came out in 1993. It was only after the emergence of the latter that I could pick up the classical threads once again. It was still more than a little difficult to believe that two important Greek antiquities could really sit there unrecognized in plain view, and there was a real worry that I was about to make a serious idiot of myself. Looking over my notes again I knew I was on sure ground with regard to the altar, and completely convinced about the potential importance of the well-head so in July 1993 I briefed John Taylor, Principal of Bretton Hall, on my suspicions.

That day I wrote again to Peter Brears at Leeds Museums to send him photos of the two Bretton pieces and broach my suspicions. The next day I received a call. It turned out that in the meantime Peter had been at Bretton Hall for a conference and took the opportunity to examine the altar and the well-head. He decided straight away to send photographs to Dr. Susan Walker at the British Museum (now Keeper of Antiquities at the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford). The altar was confirmed as antique and the well-head identified as the long-lost ‘Corinthian Puteal’, one of the most important classical marbles still in private hands in Britain. Peter sent me a copy of the letter confirming the identification and soon afterwards Dr Walker sent me copies of some of the major sources.

Briefly for now – I’ll set out all the material in subsequent instalments – it was first recorded in Corinth in 1805, upside-down in a garden in use as a well head. Soon afterwards it was bought by Frederick North, Lord Guilford and shipped to London. Detailed drawings and a clay cast were made while it was still in Greece, and fine engravings published with the early discoverers’ accounts which established its celebrity. In 1827 Thomas Wentworth Beaumont of Bretton Hall bought Lord Guilford’s house, complete with the sculptures, and after that the well-head was lost to scholarly sight. In 1861 the great expert Adolf Michaelis commenced a search but was forced to admit in his ‘Ancient Marbles in Great Britain’ of 1882 that ‘in spite of all enquiries, not the slightest trace has as yet been discovered of the sculpted puteal, a specimen of high importance to the history of art’. Three years later he published a summation of what he had gleaned thus far in the Journal of Hellenic Studies in the hope of provoking its re-emergence. In a later part I will give the whole of his account, but for now I will give his concluding remarks:

‘sometimes a happy chance may help those to discover them who remember in time what has been lost and what is to be recovered. In the present case…it is well worth the common efforts of all the English, and especially the London readers of this Journal, to search after such a capital monument as the Corinthian puteal. Who will succeed in finding it out?/ Ο μανυτας γερας εξει.

This was quite something to mull over during the summer holidays, and in September a new principal arrived at Bretton, Professor Gordon Bell, and straight away he had all this to deal with. There was some fear that the college might peremptorily sell the marbles to the highest bidder, and the very real fear that the well-head would fetch such a huge sum as to put it beyond the means of a British Museum. Professor Bell was, however, adamant that it should stay at the college, and that the college should work to secure its preservation on site.

That said, these were nervous moments. Peter Brears and Susan Walker both advised us that no attempt should be made to move them without proper appraisal of the risk. A stone conservator from the British Museum told us rather ominously that three men could have them away on the back of a low-loader in minutes. Still, it was reasoned, they had stood in their present positions without incident for over fifty years, so, as long as their true identity remained close-guarded, it seemed that they were unlikely to attract attention to themselves.

Still I was relieved to see them each morning throughout the following winter, despite the fact that their ceremonial power still bled through their anonymity and Christmas inebriants took turns to climb up on the altar and pose as statues and students in in the adjoining hall of residence festooned the well-head with coloured crepe streamers. A proper conservation report was made, and the Henry Moore Foundation offered a grant to pay for their cleaning and conservation. The following spring they were taken up, removed to an expert antiquities studio and over the next twelve months carefully cleaned and conserved.

With Michael Eastham in the studio, newly cleaned and conserved.

Photograph by David Hill, November 1995

In the studio, newly cleaned and conserved

Photograph by David Hill, November 1995

The problem now was where to find a place secure enough on site to put them on public display. For nearly two hundred years they belonged to the history of Bretton Hall, and everyone agreed that it would be best to preserve them on site, but the college had no venue that could be made remotely secure enough. Over the next few years, however Yorkshire Sculpture Park developed plans for an exciting new gallery and visitor centre, and it seemed most appropriate that they could be displayed there with the highest standards of display and security.

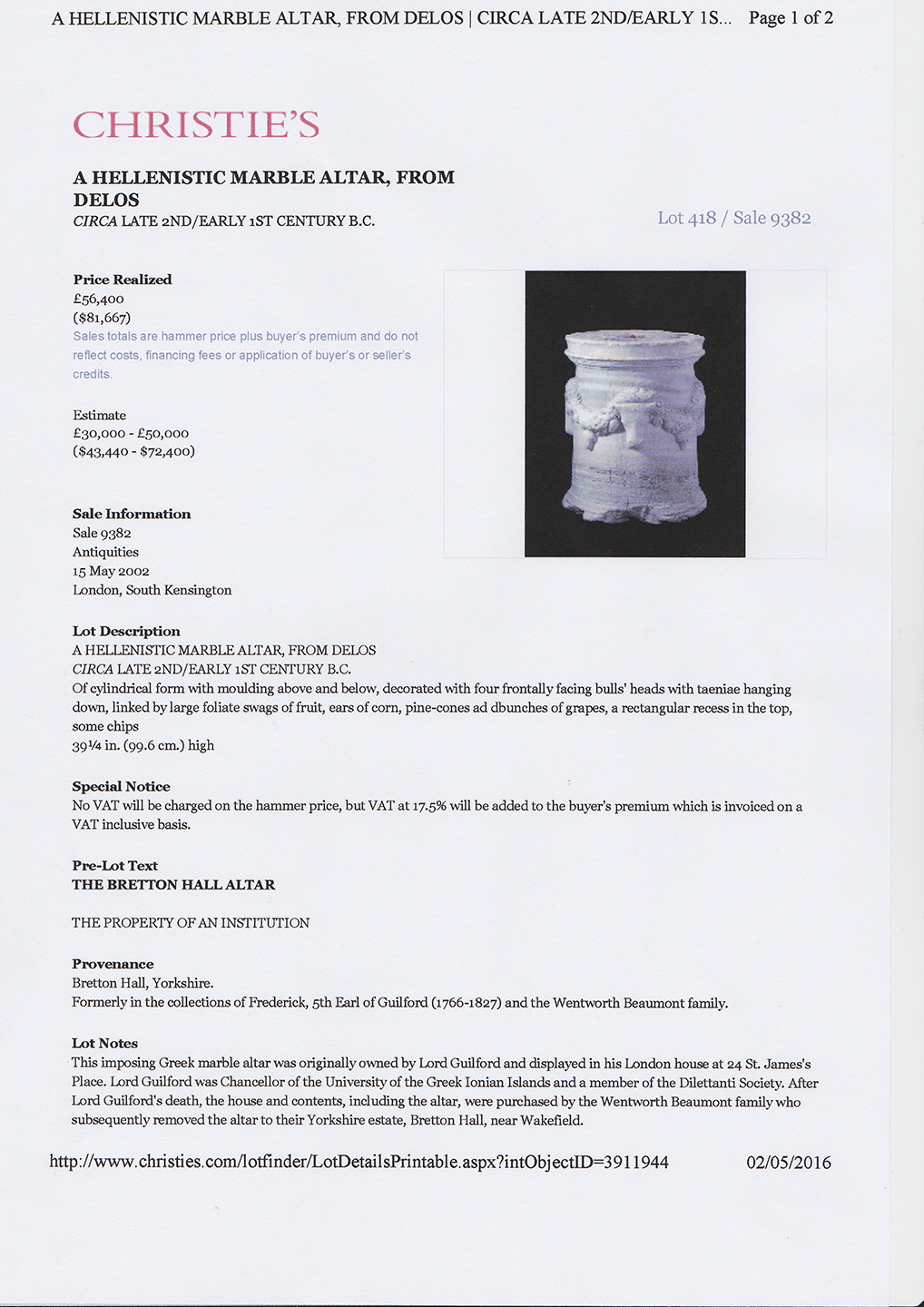

Sadly that wasn’t to work out. Soon afterwards Bretton Hall merged with the University of Leeds, and to defray the costs of that the Higher Education Funding council brokered the sale of the Corinthian puteal to the British Museum, and the altar went to auction and was bought by a private collector.

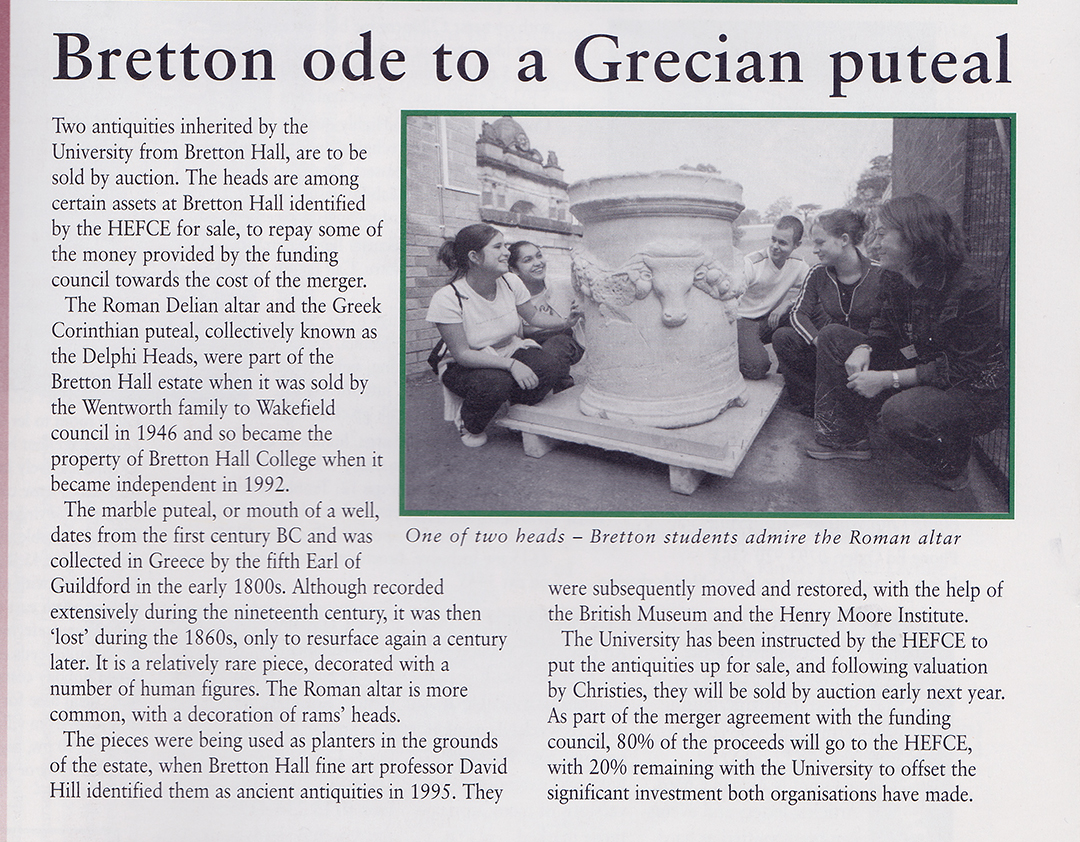

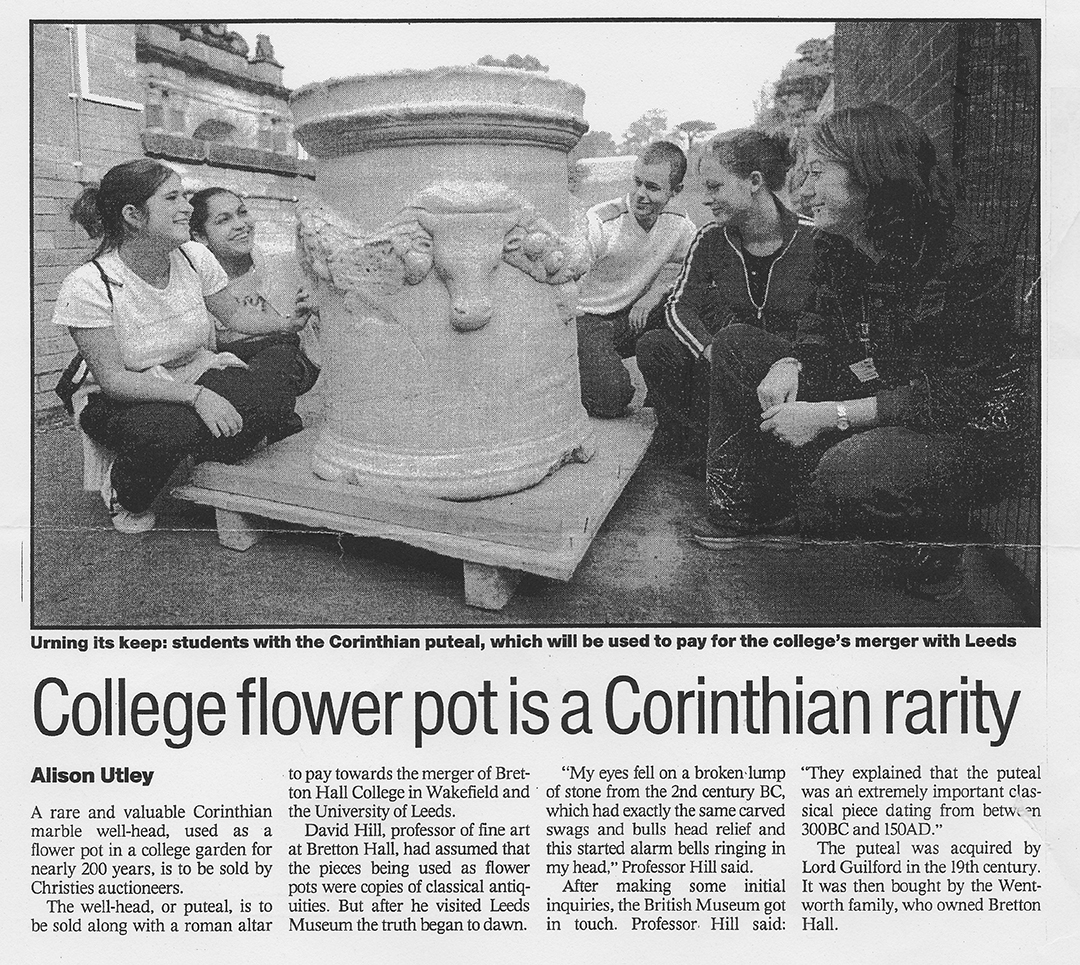

Reporting the impending sale of the Bretton Marbles.

Article by Alison Utley, reporting the discovery and impending sale of the Bretton Marbles.

To see the article in Christie’s own website click on the following link, and use your browser’s ‘back’ button to return to this page:

http://www.christies.com/lotfinder/lot/a-hellenistic-marble-altar-from-delos-circa-3911944-details.aspx?intobjectid=3911944

The Greek quotation with which Adolf Michaelis closed his article on the Corinthian Puteal: ‘Who will succeed in finding it out?/ Ο μανυτας γερας εξει’ is a line from ‘The Runaway Lover’ by the second century B.C. poet Moschus and may be roughly translated ‘He shall rewarded be’. And so it has indeed transpired. In the intervening twenty years it has given me the pretext to wander off on all kinds of research expeditions. My travels have taken me to museums up and down the country, to Paris, Vienna, Athens, Delos, Delphi, Mycenae, New York, Yale, and most recently Nikopolis at Preveza on the west coast of Greece. I have bathed in the waters of Classical scholarship, read some wonderful material and corresponded with superb authorities in the field. It has taken place almost entirely in Apollonian light, brilliant against the Aegean and Ionian Seas.

I was at Bretton Hall 1974/75. Where they there then ? If so I had no idea what they were or how old they were. I just didnt notice them.

A marvellous story, like finding a Ruskin in a charity shop. Congratulations for an exemplary bit of research.