This article proposes a source for John Sell Cotman’s famous watercolour of ‘The Ploughed Field’ at Leeds Art Gallery.

The Ploughed Field, c.1805-6

Graphite and watercolour on off-white, wove paper with reticulated grain, 9 x 13 3/4 ins, 228 x 350 mm

Leeds Art Gallery, 1923.508

Photograph by David Hill, courtesy of Leeds Art Gallery

To see full catalogue details visit

https://cotmania.org/works-of-art/41889

then use your browser’s ‘back’ button to return to this page.]

In the online catalogue of the Cotman collection at Leeds http://www.cotmania.org, I describe the watercolour as ‘the exemplar of his turn towards reticence and understatement… the supreme exercise in undemonstrative refinement and subtlety of its time’. It is one of the most travelled and exhibited of all British watercolours of its period and definitive of Cotman’s antithetical position in relation to Turner.

The originality of the subject has struck most commentators, but is best expressed by Corinne Miller in the catalogue of the exhibition ‘Cotmania and Mr Kitson’ held at Leeds Art Gallery in 1992: ‘In terms of subject matter and composition it is both revolutionary and in advance of its time. While the juxtaposition of the cultivated and the natural landscape was familiar to an audience whose countryside had been carved up and tamed by agrarian enclosures, the devotion of one third of the composition to the steeply receding furrows of the plough are without precedent and firmly establish this watercolour as one of the earliest examples of a romantic naturalism which was to take over from a ‘picturesque’ sentiment where there was no place for ‘worked’ land’.

No-one, however, seems ever to have commented on the detail at the very front of the composition, of a dead crow tied to a stick. There are several more receding into the distance. The implication is that the farmer has just set them out in the field. This is a long-used and quite widespread crop protection measure. Not long again I almost became one of the deterrents. Blundering across a newly seeded field near Jervaulx Abbey, I began to wonder about the dead crows scattered about the field. It was only when an aggrieved shout came from a nearby hedge that I understood I was wondering across the field of fire of a hidden rifleman. The signpost missed at the entrance to the field pointed away from it, not across.

No-one but Cotman seems to have led the polite viewer onto such cloying ground. Equally no Romantic painter can have confronted their audience with such a macabre detail as a crow tied to a stick. It is clear enough that Cotman was proposing a somewhat alternative aesthetic, but the Cotman literature has never managed to develop an aesthetic context in which this might be situated. My thinking about Constable’s mezzotint of ‘A Summerland’ for Sublimesites.co, however, led me to the poem ‘The Farmer’s Boy’ by Robert Bloomfield, first published in 1800 and the realisation that Bloomfield exactly mirrors the two key elements of furrow plodding and dead crows. Cotman must surely have had the poem in mind when composing ‘The Ploughed Field’.

Robert Bloomfield (1766 – 1823) was an impecunious London shoemaker when his poem was published in 1800. It became the publishing sensation of the first decade of the nineteenth century, and sold tens of thousands of copies. Given the popularity of the poem – it was already in its ninth edition by the time that Cotman painted this – it seems certain that Cotman would have read it.

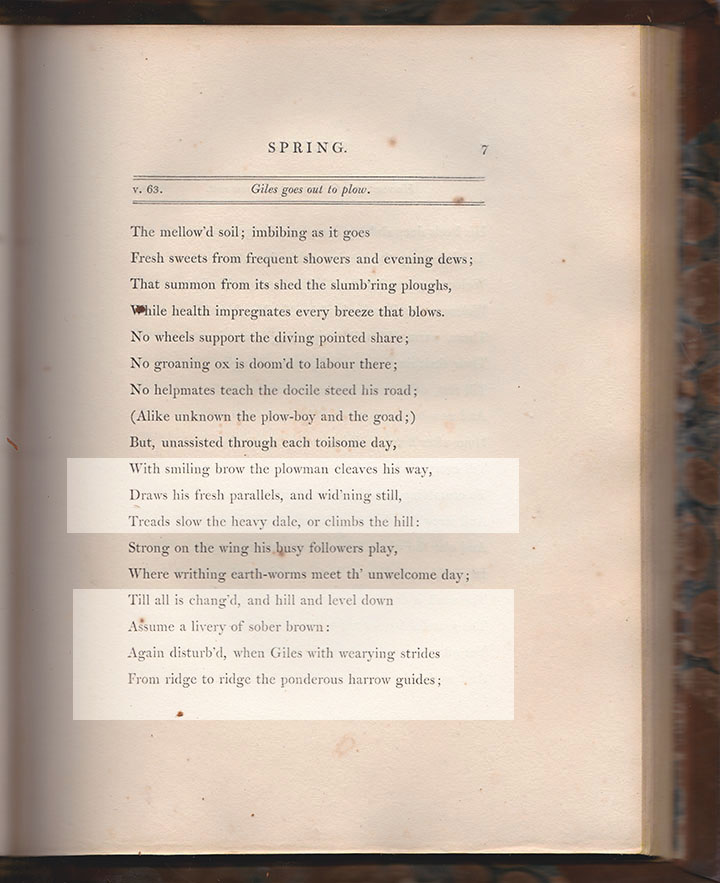

It tells the life of a simple farm boy, Giles, through the four seasons. The first part, Spring, describes the ploughing, harrowing and sowing of the fields. We can highlight the lines that most obviously relate to Cotman’s ‘The Ploughed Field’:

With smiling brow the ploughman cleaves his way, Draws his fresh parallels, and wid’ning still,

Treads slow the heavy dale, or climbs the hill…

Till all is chang’d, and hill and level down

Assume a livery of sober brown:

Again disturb’d, when Giles with wearying strides

From ridge to ridge the ponderous harrow guides;

His heels deep sinking every step he goes,

Till dirt usurp the empire of his shoes.’

This seems exactly to suggest the ground and the situation depicted by Cotman.

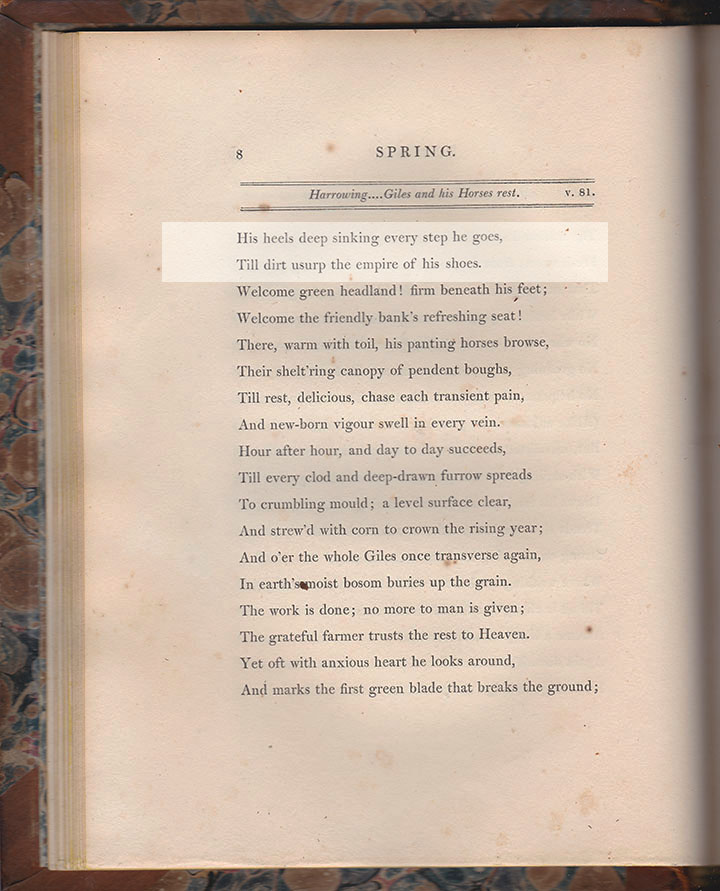

Following that comes Giles’s efforts to keeps the birds off:

‘…the big swoln grain below,

A favourite morsel with the rook and crow;

From field to field the flock increasing goes;

To level crops most formidable foes:..

Yet oft the sculking gunner by surprise

Will scatter death amongst them as they rise.

These, hung in triumph round the spacious field,

At best will but a short-lived terror yield:..

Let then your birds lie prostrate on the earth,

In dying posture, and with wings stretch’d forth;

Shift them at eve or morn from place to place,

And death shall terrify the pilfering race;

In the mid air, while circling round and round,

They’ll call their lifeless comrades from the ground;

With quick’ning wing, and notes of loud alarm,

Warn the whole flock to shun the’ impending harm.’

The conjunction of such specific and unusual details in the poem and painting seems to link them incontrovertibly. I have not yet found any specific reference to Bloomfield in the Cotman literature, but it would certainly be worth looking out for some, and nor have I made any more general search for other potential connections, although if this instance is as clear as I believe it to be, then there might certainly be others.

Bloomfield’s poem certainly caught the public’s imagination. It was directly modelled on one of the most popular rural idylls of the eighteenth century, ‘The Seasons’ by James Thomson. In all of its earlier editions it was prefaced by a biography of the poet that made clear his humble origins. One of the principal attractions of Bloomfield’s poem was that it was the authentic voice of the simple working man.

On the other hand one of the enduring scholarly issues with the poem is that in its earlier editions it was hardy Bloomfield’s authentic expression at all. The editor had very carefully smoothed out all of his colloquialisms, and most instances of unsophisticated grammar, expression and vocabulary. It was only in later editions that Bloomfield began to restore some of his original burr, but not until modern times that an edition has appeared that scrupulously adheres to the original manuscripts. See for example Peter Cochrane’s essay and edition at::

Click to access robert-bloomfield-the-farmers-boy.pdf

From a 1778 edition of James Thomson’s ‘The Seasons’

Cotman presumably, rather hoped that he might plough the same aesthetic furrow as Bloomfield. As it turned out, however, Cotman misjudged the market. It appears that the literary rural and the pictorial rural were received rather differently. If truth be told, the contemporary public simply saw Bloomfield’s poem as a new Thomson’s Seasons. Modern Bloomfield scholarship has sought to try and demonstrate more radical tendencies in ‘The Farmer’s Boy’, elements that disrupt the genteel Tory sentiment in which Thomson’s poem is steeped. See for example Ian Haywood’s article at:

https://www.rc.umd.edu/praxis/bloomfield/HTML/praxis.2011.haywood.html

Furthermore, the whole orthography and design of the book seems to have been intended to deceive the reader into thinking that ‘The Farmer’s Boy’ was the exact successor to Thomson’s Seasons. The woodcuts are twee to the point of being positively kitsch. They seem the calculated attempt to smuggle the idea of rural life out of the country and into the drawing room, and to neutralise any but the sweetest perfumes that might drift in from outside.

The trouble is that Cotman’s attempts in the same genre were all too visibly antithetical. Pictures were supposed to be big, rich, finely wrought, valuable and covetable objects. ‘The Ploughed Field’ fails on virtually every level. It is small, fragile, muted, artisanal in is handling, and depicts dirt and dead crows. Cotman made the notion of a simplified language and anti-heroic aesthetic far too concrete. He made something resembling arte povera about one hundred and fifty years too soon. One might say in fact, is that ‘The Ploughed Field’ is the kind of illustration that ‘The Farmer’s Boy’ properly deserved and certainly one might suspect that Cotman intended the association to be recognised, besides his realisation of the true nature of Bloomfield’s poem. As I observe in the commentary on the watercolour in http://www.cotmania.org: ‘It represents the complete antithesis to the strident, clamouring competition that for the most part was art in exhibition in the early nineteenth century: So antithetical, in fact as to exceed all context for its age, and it continues to challenge expectations in a visual environment that has taken a taste for the histrionic to hyperbolic levels.’

Postscript

I was led to Bloomfield’s ‘Farmer’s Boy’ via my interest in Constable’s ‘A Summerland’. Constable quoted a couple of lines from the poem as an epigraph to the painting in the catalogue when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1814:

‘But, unassisted through each toilsome day,

With smiling brow the Plowman cleaves his way’

It is a remarkable coincidence that these lines stand at the beginning of the passage which appears to have caught Cotman’s eye – about half-way down page 7 of ‘The Farmer’s Boy’ reproduced above. Constable drew on Bloomfield on several occasions. I hope to give some thought to his relevance to ‘A Summerland’ in due course.

2 queries

Has the field been sown yet? Is Cotman collapsing two events? And is this acceptable, does Constable take such liberties with farming practise?

And

Where was this exhibited?

Hi Fiona

Thanks for your comment and interest. If I’m right about the connection with Bloomfield, then the clear implication is that the field has recently been sown, and that the dead crows have been put out to deter the birds from taking the seed.

I’m not sure that I see anything in the picture that militates against that, but I would be the first to admit that I’m not an expert on farming practise, and would be glad to receive advice!

Your implication about Constable, however, is, I think, well-founded. As Michael Rosenthal showed in his book on Constable, the artist very well knew the practises of Suffolk and Essex farming. I would certainly agree that Cotman’s art does not seem so deeply planted in the earth.

DH

With regard to the exhibition, there is no record of it being exhibited in Cotman’s time. In fact the first we hear of it at all in the historical record is when it turned up at Palser’s Gallery in 1923, from where it was bought by Leeds Art Gallery.

A farmer pointed this out to me and I thought that he may be responding to ? text as the poem if it’s a source is more a narrative than a description rather than reality ? As a townsman s son?

Cotman’s father was a hairdresser, and later a milliner. But Cotman did marry a farmer’s daughter…