This article considers the eighteenth work of twenty-five bought at Anderson & Garland Ltd, Newcastle upon Tyne, 21 March 2017, lot 46 as Various Artists (British 19th Century) Sundry drawings and watercolours, mainly topographical and floral studies, including a grisaille “South Gate Lynn, Norfolk”, bearing the signature J.S. Cotman, various sizes, all unframed in a folio.

Thus far we have been concerned with subjects at the main centres of the Twopeny family at Woodstock Park in Kent and the Old Rectory, Little Casterton, Rutlandshire. Here we venture beyond the main sites, to accompany the family, or some representative of it, on a tour to Scotland.

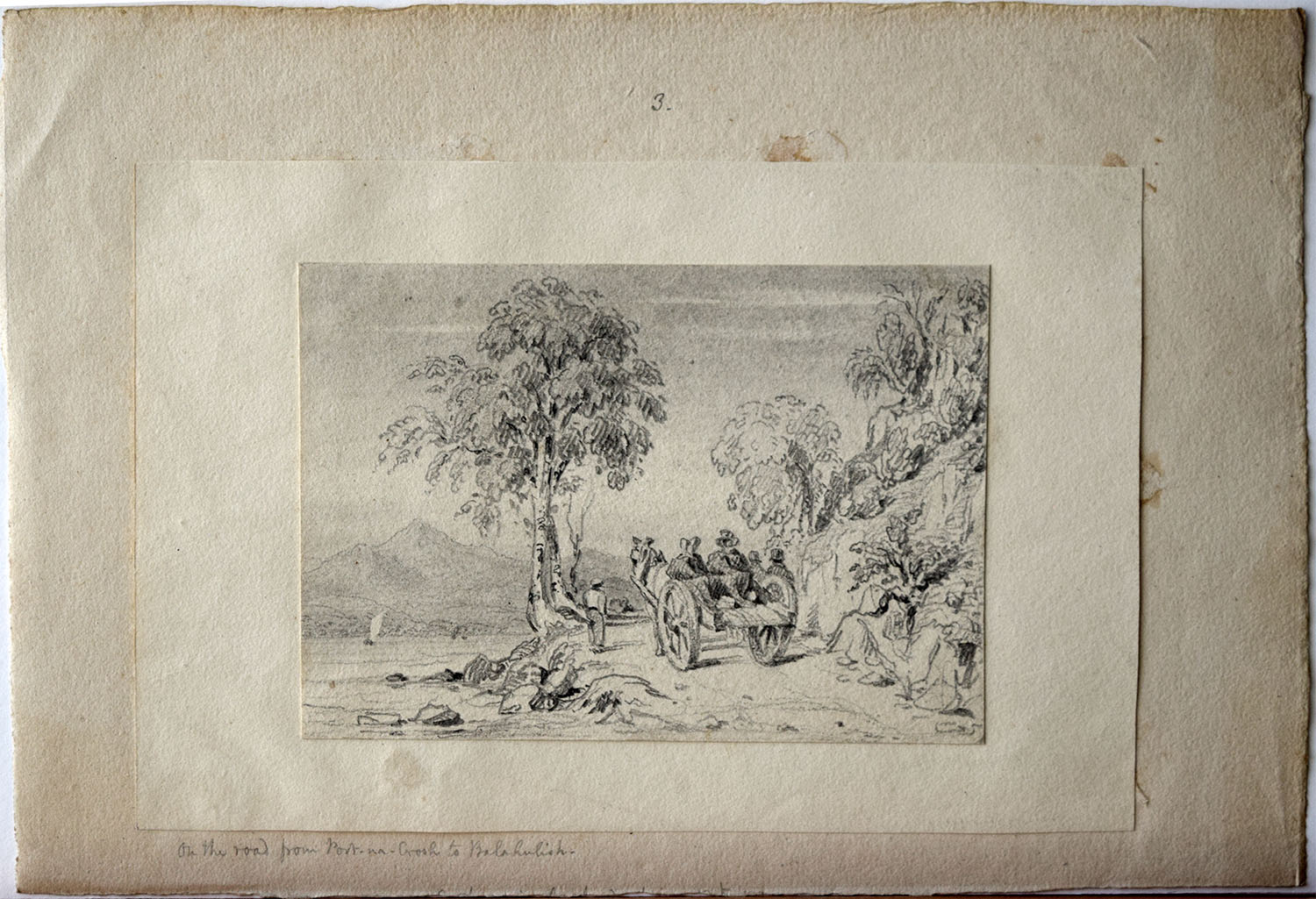

A Mountain seen over a Loch, Scotland. Called “On the road from Port-na-Crosh to Balahulish”

Pencil and watercolour on medium-weight, stiff, cream, wove paper, 100 x 145 mm stuck down on backing sheet of similar cream wove paper, 142 x 212 mm, in turn mounted onto a second backing sheet of softer medium-weight, cream, wove paper, 187 x 274 mm.

Inscribed in pencil on mounting second mounting sheet below left “On the road from Port-na-Crosh to Balahulish”, and numbered in pencil centre of margin of same sheet, above, “3”. Numbered in pencil on reverse of backing sheet in top left corner, “45)”

This is a carefully-drawn, small, pencil, landscape of a mountain seen over a lake to the left, from a rough road on the shore to the right, where a horse draws a two-wheeled cart. There are two passengers, evidently elderly ladies under heavy cloaks. The cart is led by a boy to the left,, and accompanied by two well-dressed gentlemen to the right. Two birch trees grow on the shore in the centre of the composition and a rough wooded bank rises steeply at the right.

The landscape has the character of Scotland, and this is supported by the title inscribed below, “On the road from Port-na-Crosh to Balahulish”. Portnacroish is on the shore of Loch Linnhe in the west of Scotland a few miles north of Oban.

The road follows the east shore of the loch northwards to Ballachulish on the narrows between Loch Linnhe and Loch Leven.

Despite the specific information given by the inscription it proves difficult to identify an exact subject for the drawing. The three main mountain massifs across Loch Linnhe are Creach Bheinn (853m) and Garbh Bheinn (885m) seen successively to the north-west as one progresses from Portnacroish to Cuil Bay. The loch disappears from view at that point behind Ardsheal Hill and when the lochside is regained beyond Kentallen the prospect is to Meall Breac and Sgurr na h-Eanchainne (730m) above Ardgour. None of them present a profile at all like that in the drawing.

All this is to presume that the drawing should offer some recognisable relation between what is drawn and what is depicted. For a drawing is not at all like a photograph and it is only in the hands of competent draftsmen working in a tradition that only really began in the later eighteenth century that we can have any expectation of such relation in art. It seems plain, in any case, that the drawing is too elaborate and considered to have been made on the spot. The cart would have had to remain stationary for an inordinate length of time. Rather the effect of instantaneity is entirely synthetic. The configuration of figures and cart especially must be from the imagination. An imagination informed by knowledge and memory, but imagination nevertheless.

On close inspection, the figures are remarkably well characterised. We can see two mature [one might say] women in the cart, rather ungainly seated in an uncomfortable vehicle. They are well [if not to say miserably] wrapped up against the elements and are being bumped and lurched along the road whilst their male companions march along in Wordsworthian seriousness and conversation. An artist that can extract such implication from a few strokes is quite capable of giving an accurate mountain profile should it be of interest.

There are perhaps grounds for suspicion that the inscription ought to be set aside from the drawing. When one examines the way in which the inscribed backing sheet relates to the mounted drawing, it becomes apparent that there might be an issue.

The fact is that the glue patches on the inscribed backing sheet do not at all match those of the mounted drawing. It would appear that the glue patches relate to a sheet that was rather larger than that which is currently affixed in place. It is not hard to imagine that the original drawings on this sheet became detached, and were reattached, but not in the right places. So, the original drawing of “On the road from Port-na-Crosh to Balahulish” is now missing, but the present drawing was put there in its stead. I might observe in support of this idea that the lower edge of the sheet has been torn right through another line of pencil inscription, presumably the title of another work that was mounted below. It seems hopeless that the torn inscription will ever be recovered.

So the possibility arises that the present subject is something entirely different to that imputed to it by the inscription.

But where? The truth is that such steep profiled hills rising from lochs are not that common in Scotland. Highland mountains are mostly old and worn, and generally present lumpen or hummocky outlines. So much so that where a mountain cuts a strong profile, it tends to have been frequently pictorialized. The principal historical example is Ben Lomond seen from the northbound road on the shores of Loch Lomond. I have already written about a treatment of that view by Turner on Sublimesites.co 12 May 2018

Another, equally famous profile, is that of Ben Venue in the Trossachs. The area was made famous in Victorian times by Sir Walter Scott’s Lady of the Lake published in 1811, in particular the views of Ben Venue over Loch Katrine on the west flank and Loch Achray on the east. Turner sketched extensively in the area in 1831 [see sketches on Tate website], and painted watercolours [British Museum, Yale Center for British Art] of each aspect to be engraved in Scott’s works.

On the eastern approach to Loch Achray and Ben Venue from Callendar the mountain is first well seen about half-way down the north shore of Loch Venachar, where the road first comes down to the shore. That particular station has sufficient potency to have given rise in recent years to a café, recently upgraded to a restaurant, the Venachar Lochside.

The profile is sufficiently close to that of the drawing for the identification to seem plausible, but it might require a little more evidence to become certain.

One piece of evidence that we should weigh before closing, is the number inscribed on the back. This puts it in series with several other examples in the portfolio, numbered in similar style, and all apparently pages from an album. The mounting sheet in the present example is the same kind of paper as other mounting sheets in the series. The majority of the drawings from this album are given here to the Reverend David Twopeny, about whom we have heard a good deal in the series thus far. The main characteristics of his drawing style are the sensitive treatment of architecture, especially sophisticated treatment of trees and vegetation and sensitive and deft drawing of figures and animals.

It is not impossible that the present drawing is by him. The figures and horse and cart are excellent; but the treatment of the vegetation is nowhere near the standard of the previous drawings. The standard of figure drawing, however, appears to have been shared by his sister Susanna, and on the evidence of other drawings attributed to her in the portfolio (parts #15, #16) she appears to have had less feeling for the vegetation. One would have expected more in this department from David Twopeny; perhaps this could alternatively be by Susanna.

We cannot guess the occasion. Susanna remained a spinster, and thus enjoyed a lifelong freedom to travel. We will see a dated instance of this in the next instalment. David Twopeny had responsibilities to his Ministry, but found the opportunity to make at least one tour to Scotland in August 1872. The expedition made him enduringly famous. On a boating excursion on the Sound of Sleat to the east of Skye he spotted, and drew, a giant sea serpent breaking the surface of Loch Hourn. His report was published, with sketches, in the May 1873 edition of the journal The Zoologist and has occasioned speculation and discussion ever since. It would be just too much to hope that this drawing originated from that same tour.

TO BE CONTINUED

Next, on tour to Wales with Susanna Twopeny