This article considers the seventeenth work of twenty-five in a portfolio bought at Anderson & Garland Ltd, Newcastle upon Tyne, 21 March 2017, lot 46 as Various Artists (British 19th Century) Sundry drawings and watercolours, mainly topographical and floral studies, including a grisaille “South Gate Lynn, Norfolk”, bearing the signature J.S. Cotman, various sizes, all unframed in a folio.

Here we consider a fine watercolour of the Interior of Little Casterton Church, which is inscribed with the artist’s name ‘C.Twopeny’.

The Interior of Little Casterton Church, Rutlandshire

Pencil and watercolour on medium-weight, smooth, white, wove paper, stuck down on backing sheet of similar white, wove paper, and trimmed to 248 x 184 mm. The whole mounted on a a sheet of oatmeal [possibly originally white] commercially-produced ‘mounting board’ [so stamped in top left corner]

Inscribed in pencil on mounting board below image, ‘C Twopeny’ to left and ‘Little Casterton Rutlandshire’, to right.

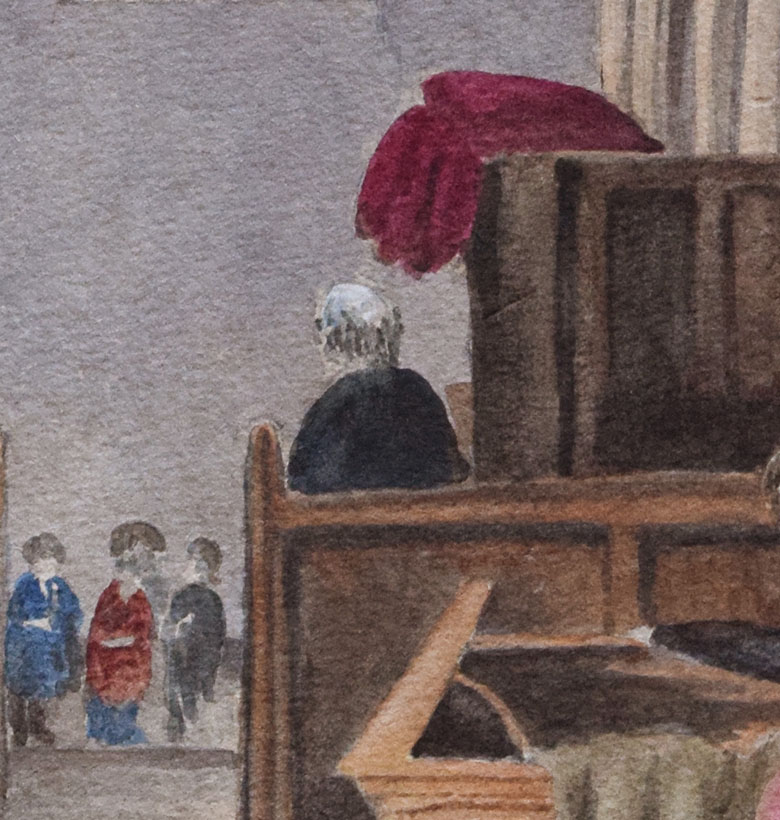

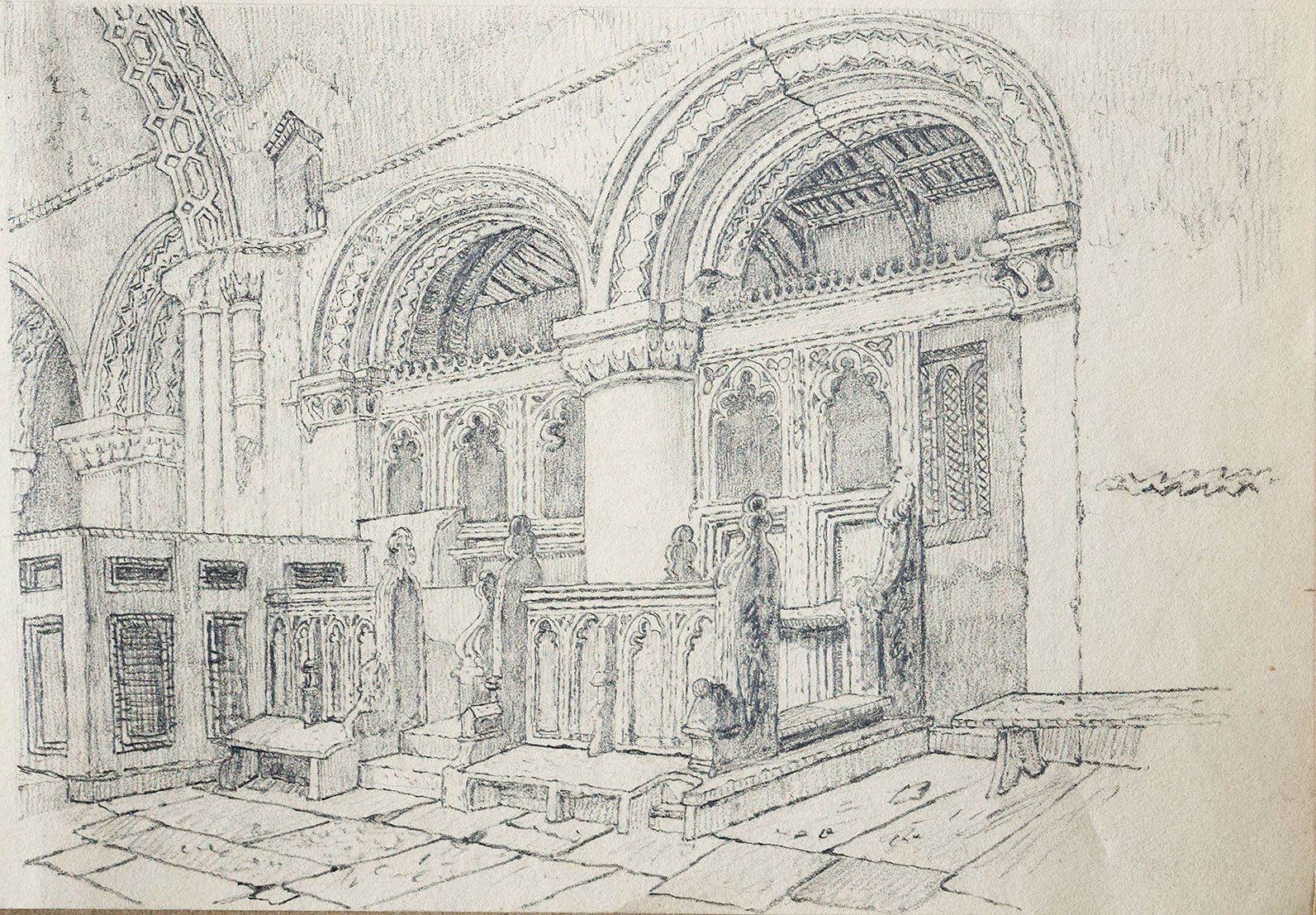

This is a carefully-wrought and delicately-coloured watercolour of the interior of a small church. We evidently look toward the nave where two large round arches, supported on plain cylindrical columns, open onto aisles either side. There are box pews to either side and in the centre foreground a large two-figure brass monument let into the floor of the chancel. About half-way down the church on the right, under a shallow-pointed chancel arch is a tall pulpit with a large crimson cushion, no doubt for supporting a bible when in use. The nave has a small lancet window in its end wall, and two clerestory windows either side, supporting a fine timbered nave ceiling.

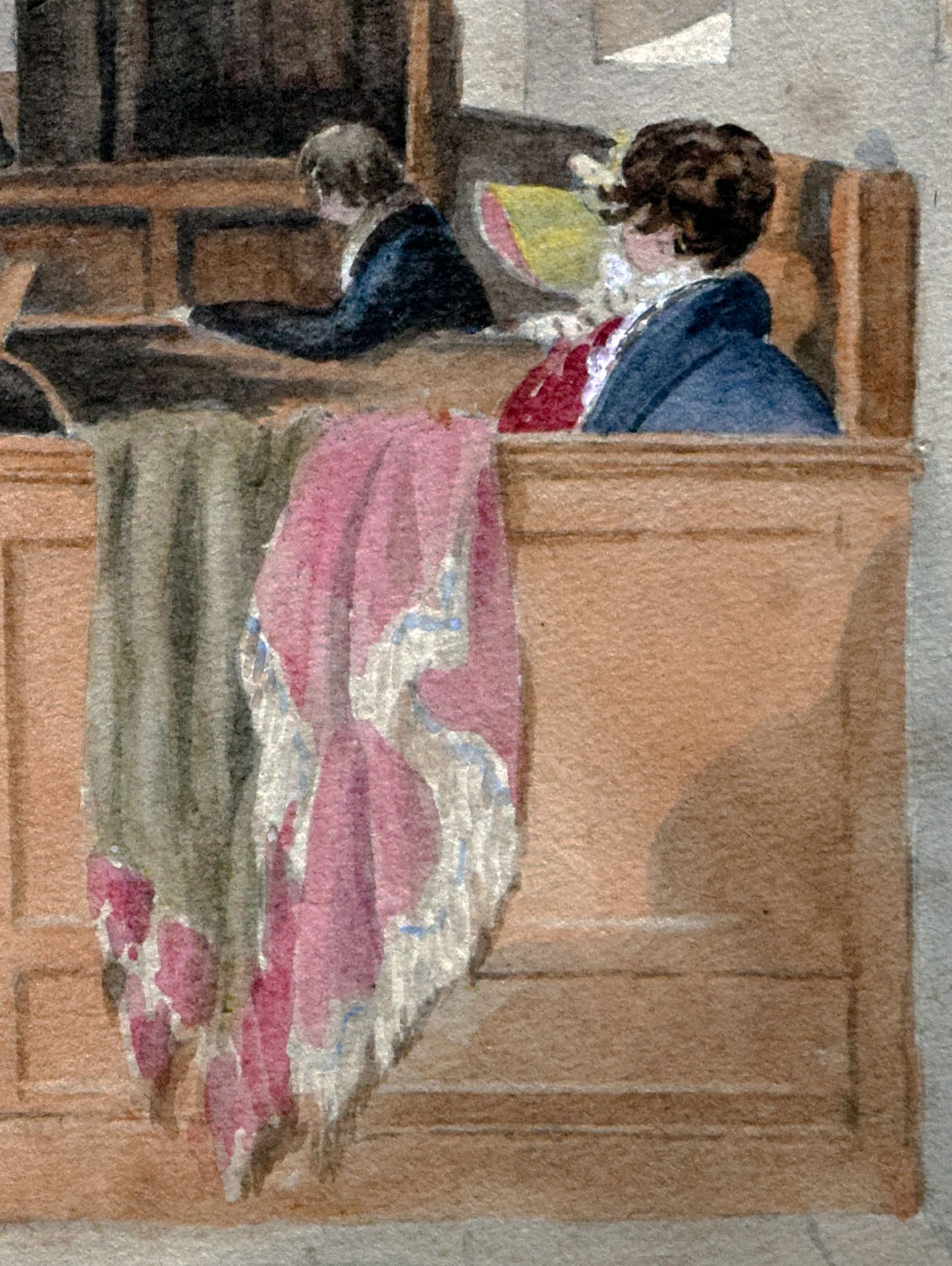

The composition is notable for its figures. In the right foreground is a young couple, the man dressed in a blue coat and the woman in a red dress and green bonnet with a pink lining. They are evidently well-to-do, for she has also brought a copious gown in matching green and pink, which is cascading over the near edge of the pew. A slightly older man [apparently] sits slightly beyond the couple leaning slightly forward in his seat, with his arm extended along the pew rail. He is evidently listening to the preacher beyond who is standing at the foot of the pulpit and appears to be addressing the congregation in the nave.

In the foreground to the left is a young boy sat next to a very well dressed older lady. She wears a red gown with lace collar, and a large black bonnet trimmed under the brim with lace. She has before her a large folio book, propped on the front rail of the pew, and cushioned on a length of cloth, blue silk or damask to judge by the way it appears shot through with a contrasting pink. The cloth cascades down onto a rustic trestle on the top of which is arranged what appears to be a sheaf of corn, or a bundle of hay.

Opposite the pulpit is a large box pew, in which we can see the heads of two men and perhaps the blue bonnet of one woman. Beyond that is a series of lower pews, where we can see one woman seated wearing a red jacket and a brown (or yellow) bonnet. Finally, on benches against the far wall of the church are seated three or four more devotees. Two are women, one in a blue robe, another in red. Besides them is another figure, probably male, dressed in a grey or black jacket. Behind them is possibly a fourth figure, evidently dressed in a bicorne hat.

Photograph taken by Professor David Hill, 6 February 2020

The subject is as inscribed the interior of Little Casterton Church. The scene is eminently recognisable today, looking west from the altar rail. The pews and pulpit have been renewed, but the original simple rood divide survives.

The brass is six hundred years old and represents Thomas Burton of Tolethorpe (d.1381) and his wife Margaret (d.1410) and is generally covered with a carpet for protection. The font has been resited at the west end. Apart from a slight accretion of details, it is remarkable how like the watercolour the church remains. In the watercolour, light enters over our left shoulder, i.e. somewhat south of east, so the time of day must be about nine o’ clock in the morning.

This sheet stands apart from the main group of pencil drawings in the portfolio; all by a distinctive hand, on similar paper as one another, and all similarly mounted and inscribed. Some of the sheets are inscribed with a number, probably indicating the pagination of the original album. The present drawing aligns with some of these in terms of its Little Casterton subject, but is distinguished by being in watercolour, and in a different hand altogether.

The principal subjects in the portfolio, Woodstock Park in Kent and Little Casterton align perfectly with the main loci of the Twopeny family. The main branch of the family were established in a successful legal business associated with Rochester Cathedral. The family established its main seat at Woodstock Park in the later eighteenth century, and a scion of the family, Revd Richard Twopeny took up the living of Little Casterton in 1783 and held it until his death in 1843.

Some branches of the family were extremely prolific. Rev Richard’s elder brother Edward had eight children, and the Revd Richard had ten. The vast majority lived to adulthood, and many were long-lived.

Looking through the family tree, ‘C Twopeny’ could be Rev. Richard’s younger sister Charlotte. She was born in 1760 and married William Hussey of Ashford in 1781. He was rector of Sandhurst in Kent 1781 to his death in 1831, and she died not long after in 1833. She might be an outside contender.

Rev. Richard also had a daughter Charlotte, born in 1790. Michael Cayley has established the outline of her life on Wikitree. She was baptised 5 November 1790 in the church at Little Casterton: She was left £500 by the will of Anne Barker of Lyndon, Rutland who died in 1846. Two other of her sisters were also beneficiaries, but the connection with the testator is unclear. Charlotte appears at that time to have been unmarried for the others are addressed by their married names. The 1851 census records her in Stamford aged sixty, and the 1871 census records her in Torquay aged eighty. She died in 1878. So in the most likely period in which this watercolour could have been made, say the early 1830s, she would have been forty years of age, or just over. Presumably as a spinster, she might have continued to reside at the Old Rectory until the death of her father in 1843. She might be a serious candidate.

There are, however, two further possibilities. Brothers David and William Twopeny, both highly skilled amateur artists about whom we have heard in previous instalments, had two sisters, Charlotte and Catharine. Michael Cayley has provided detail on both. Charlotte was born in 1801 and remained a spinster. In 1851 she was living with her elder sister Susanna, also a spinster, in Walter, Kent. By 1861 both were living in at the family seat at Woodstock Park, as part of the household of their brother Edward, and both remained there to their respective deaths, Charlotte in 1874 and Susanna sometime after 1875. We have already suggested Susanna as the author of the Tolethorpe Mill sepia watercolour, which is initialled ‘ST’ (see part #15) and we will come soon to another watercolour by the same hand in the portfolio. The two unattached sisters might well have had the leisure to become accomplished artists and would no doubt have been welcome visitors to their kinfolk at Little Casterton.

Charlotte’s younger sister, Catharine, was born in 1807. In 1830 she married Richard Twopeny (b.1794), the second son of Rev Richard Twopeny. At the risk of causing genealogical confusion, he, too, trained for the ministry and in 1824 settled into the living of the Oxfordshire parish of North Stoke, later becoming Vicar of the contiguous parish of Ipsden, and remaining there until his death in 1871. Catharine followed him to the grave in 1874. As a married woman, living away at the putative date of the present watercolour, she might be considered unlikely. We have, however, already established a concrete connection to Catharine in the portfolio in that her name is inscribed on the back of the sepia watercolour of Tolethorpe Mill. On balance, I suspect that the inscription more indicates her ownership rather than authorship.

We might, however, give some thought to what might have been the occasion for the present watercolour, and who might constitute the dramatis personae.

Let’s start with the older lady in the box pew to the left. Her pew in the chancel is a sign of high rank in the community. She must surely be identifiable as Mary, Dowager Countess of Pomfret of Tolethorpe Manor. She married George the third Earl in 1793. The Pomfret seat was at Easton Neston in Northamptonshire. The title and estate passed to George’s brother, Thomas, as the fourth Earl, but he survived only until 1833 when the Earldom descended to his son George Robert. The death of the third Earl in 1830 was the occasion of the Countess returning to her old family seat at Tolethorpe Manor and her black bonnet is perhaps a sign of her widowed condition. The fifth Earl was her nephew, but he was only nine years old on his inheritance in 1833. Presumably it is he that accompanies her, and to judge from appearance, probably at about the time of his inheritance.

The preacher must be the Reverend Richard Twopeny, who in 1833 passed the fiftieth year of his ministry and the seventy-sixth of his life. He marked his seventy-fifth birthday by joining with the Countess of Pomfret to found and build a school near the church [see part #13]. His venerability explains the perfect silver of his hair, and also, perhaps, the fact that he preaches from below the pulpit. As it turned out, he had a whole decade of further parish ministry to enjoy.

Presumably the figures seated in the nave are the wealthier villagers, particularly those in the large private box pew opposite the pulpit. By inference we might conclude that the figures at the far end of the church comprise less wealthy members of the congregation from the cottages of the village.

So what might we make, finally, of the figures to the right? We have already noted the privileged position of the Countess of Pomfret’s box pew. There was no-one more eminent in the parish than her, so the figures to the right, in boxes directly opposite the Countess, must be special guests, celebrants, or family of the vicar. The couple in the foreground have the greatest prominence, and by virtue of that have some implied role in the occasion of the watercolour. They must be married to be sitting together unchaperoned, but only recently so to judge from their apparent age. We can tell little of her except through her beautiful outfit, but he is quite distinct, and certainly in the prime of his maturity. The artist carefully delineates his thick, dark hair and pink complexion, and gives his bearing a sense of vigour. We cannot know for certain but it is tempting to wonder whether this might be David Twopeny and his wife, Mary. We have already heard a good deal about David Twopeny as the author of the main series of drawings in the portfolio (see parts #3ff). Mary was the youngest daughter of the Reverend Richard. Both were thirty years of age when they were married in Little Casterton Church on 29 May 1834. The watercolour answers well to that date if the identification of the Countess of Pomfret and her nephew is correct.

My first thought was that this might even be a representation of the wedding. That is not impossible – it could represent the closing parts of the ceremony after the couple had been married, and white dresses were not so ubiquitous in those days – but there are no conclusive signs of a wedding as one might expect if that were the intent of the picture. Nonetheless the blue day coat, and beautiful bonnet and shawl do seem to argue a special occasion. And the underlying poetic is of couples, hinted in the historic couple in the brass on the floor. If we were to follow through the logic of this discussion, we might even say that on one side is a couple parted, embodied in the lone figure of the Dowager, and on the other side one recently joined.

The artist appears to have felt the need to avoid direct portraiture, but nonetheless invests the figures with distinct character. Moreover, the paint handling is well above the normal level of an amateur. The treatment of light is especially impressive – the sunlight on the box pew in front, and atmosphere in the distant nave – all suggesting a well-trained visual imagination, and a determination to properly inform and consider each effect in detail.

Interior of Trentham Church, Staffordshire, 1806

Graphite and watercolour on buff, laid paper, 545 x 410 mm, 21 7/16 x 16 1/8 ins

Norwich Castle Museum, NWHCM : 1947.217.133

This drawing suggests the influence of Cotman at least as strongly as any other in the portfolio. It is the first, however, to suggest a direct familiarity with his fully-coloured watercolours. Cotman made a speciality of delicately coloured church interiors. From his establishment in Norwich in 1806 they provided some of his favourite subjects. From his first masterpiece in this genre, The Interior of Trentham Church of 1806, through the aisles of Norwich Cathedral

Norwich Cathedral: Interior of the North Aisle of the Choir, Looking East, 1829,

Graphite, watercolor, and gouache on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper,

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1975.2.510

to the quiet chancels of Norfolk, and on to the naves of Normandy, he created a signature series of subjects, in watercolour mostly characterised by a transcendent stillness. Even in a busy cathedral he creates a quiet poetry of colour, floating brilliant highlights against subtle muted harmonies. The tradition was ably continued by John Sell Cotman’s eldest son, Miles Edmund, particularly in the late 1830s and 1840s.

Interior of Attleborough Church, 1838

Pencil and watercolour on paper, 144 x 209 mm

Norwich Castle Museum, NWHCM : 1951.235.702.B10

Once again in the portfolio, we encounter a drawing that begs some explanation of how the artist could have developed a familiarity with Cotman’s work, and assimilated it so finely. There is one Cotman sepia drawing of The South Gate, King’s Lynn in the portfolio (see part#2) and a copy of church interior subject in The Chancel of Walsoken Church (see part #3), but the present watercolour offers evidence of familiarity with a very particular strand of his watercolour practice.

We do know that the Twopeny family were involved in antiquarian interests. William Twopeny has already been mentioned in relation to the multitude of his antiquarian drawings at the British Museum, and we will consider one particularly good example of his work in the portfolio in due course. Antiquarianism might have brought members of the Twopeny family into contact with Norfolk antiquarians such as Dawson Turner of Great Yarmouth or Revd James Bulwer of Aylsham, who were both closely and directly involved with Cotman. Perhaps even it was through Dawson Turner’s six daughters, to whom Cotman gave lessons, and who had the opportunity to observe Cotman’s practice on an almost daily basis over twelve years that the artist was resident in Yarmouth and engaged as drawing master to the family. Hopefully, evidence might be discovered some time to establish a connection.

Acknowledgement:

I am indebted once again to Michael Cayley, who has supplied valuable genealogical information on the Twopeny family. Readers may explore his researches on Wikitree. Follow this link to a good place to begin.

TO BE CONTINUED

That concludes the Little Casterton subjects. In the next instalments we will venture further afield to Wales and Scotland.

This is very interesting to me – one of Richard Twopeny’s daughters, Rosamira, married Rev Robert Bateman Paul (who is buried at Little Casterton) and they had three daughters. Rev Robert Bateman Paul was a member of the Canterbury Association, who orchestrated a mass emigration to the Canterbury region in New Zealand in the 1840s/ 1850s.Robert Bateman Paul and Rosamira emigrated and lived in New Zealand for several years before returning to Little Casterton. Interestingly the Caley’s wikitree only has the two daughters – the third daughter, Harriet Maria Paul, married Edward James Lee in New Zealand (a prominent pioneer, later politician) and I am a descendant of Edward James Lee and Harriet Maria.

Thank you for getting in touch. It is astonishing how wide a network of relations the Twopeny family formed. This is even more amplification to the theme of expanding horizons that developed as I worked through the drawings. I am sure that Michael Caley will be interested in your update to the family tree. I will forward your message to him. Thanks again. DH