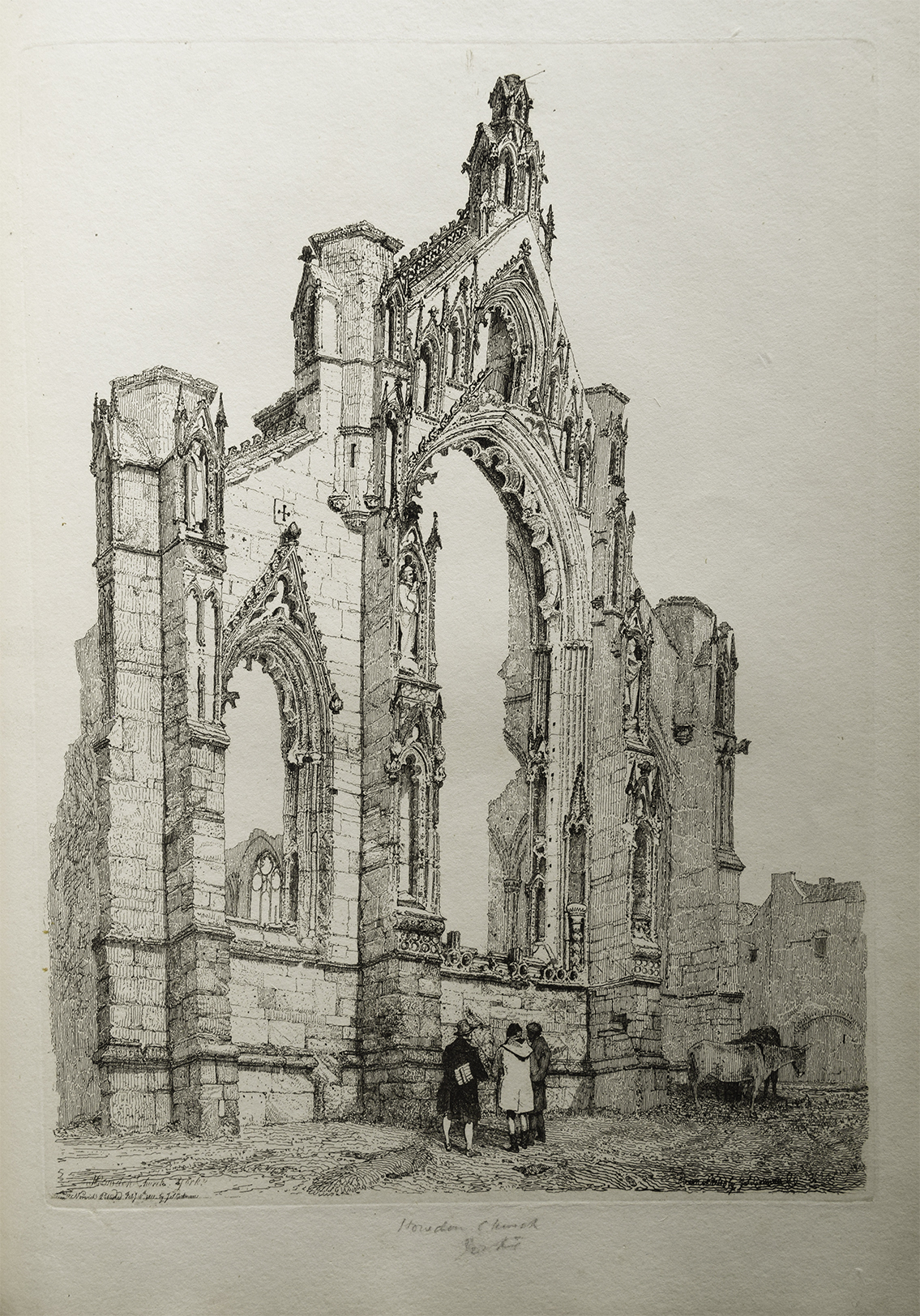

This is the twenty-eighth article in a catalogue of John Sell Cotman’s first series of etchings published in 1811. Here in plate 23 Cotman presents one of the Yorkshire subjects that he held in highest esteem, and provided one of his most important early compositions.

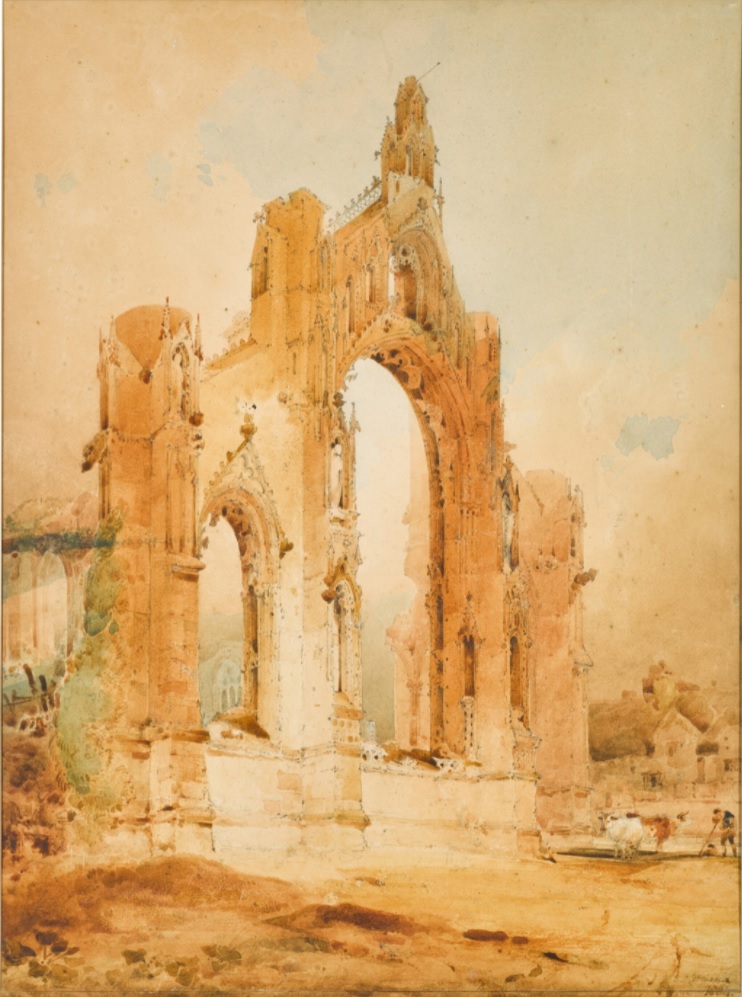

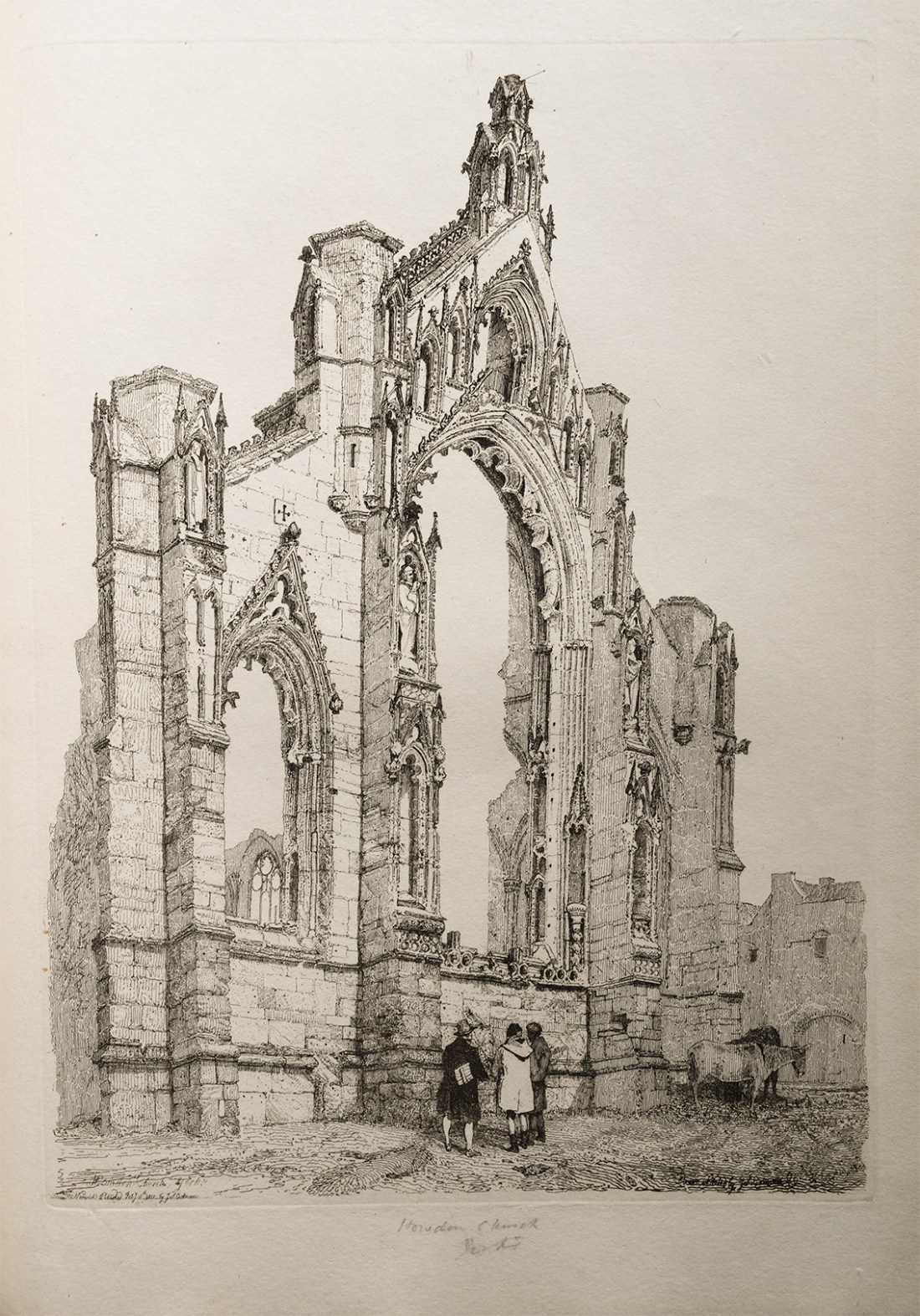

East end of Howden Collegiate Church, Yorkshire, 1811

Private collection

Photograph: Professor David Hill

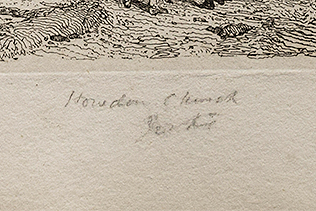

This is an upright composition of the remains of a grand medieval church seen from an oblique angle to the left. A large central window under a crocketed canopy is flanked by two similar, but smaller, aisle windows. The windows are flanked by buttresses carrying canopied niches. The gable above the central window is pierced by a small widow at the centre, flanked by ascending niches. The whole is in a state of dilapidation. The window tracery is lost, the church roof is missing and substantial parts of the side walls have collapsed. The subject is identified in a title scratched somewhat indistinctly lower left: ‘Howden Church, Yorks’. Below that Cotman has inscribed ‘Norwich, Published Feby 5th 1811 by J.S.Cotman’ and to the right, barely legibly against the grass, ‘Drawn & Etched by J.S.Cotman’. Impressions gathered into the bound edition of 1811 were additionally inscribed in pencil lower centre with the title ‘Howden Church/ Yorks’. It is listed here with the title that Cotman gave it in his list of subjects in the published edition.

The plate was etched by Cotman for his first series of ‘Etchings by John Sell Cotman’. This was issued to subscribers in parts, and the present subject formed plate 23 in the complete edition as published in 1811. It is the fourteenth plate of the series in date order. At the beginning of 1811 Cotman gained his full confidence in etching, and tackled a series of his largest plates. This is the largest of all, and is dated 5 February, little more than a week after the previous largest plates of Easby Abbey (plate 20) and Crowland Abbey (plate 22). Although it was finished just a little over halfway through the sequence, Cotman held it back to the end of the published order, so that it could form part of the series finale.

Right click on image to open full-size in a new tab. Close tab to return to this page.

Howden is about half-way between Leeds and Hull, just north of the river Ouse where it begins to open out towards the Humber estuary. It was an important centre from Saxon times. The present church was built in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. When the tower was added in the 15th century, it commanded a vast horizon of rich agricultural land stretching from the Yorkshire to the Lincolnshire Wolds, and westward almost to the Yorkshire coalfields.

Photograph by Professor David Hill, 7 February 2024, 11.50 am.

Cotman’s subject is the east end of the church seen from the south east. He visited Howden in 1803 at the end of his first visit to Yorkshire. After staying with the Cholmeley family at Brandsby Hall, and exploring something of the county from there, he joined Mr and Mrs Cholmeley and their son Francis on a tour of East and West Yorkshire, during which they visited Beverley, Hull, Welton, Howden, Selby, Leeds and Wakefield. They set out from Brandsby on 14 September. The story is told in greater detail in my book, Cotman in the North, (Yale University Press), 2005.

Right click on image to open full-size in a new tab. Close tab to return to this page.

His exact viewpoint is outside the manor house but is today obscured by trees. This is a little frustrating, but it does appear that the intervening growth is reaching the end of its life, and perhaps Cotman’s view might soon re-emerge.

The choir and great east end were built in the early 14th century as the culminating part of the church, and was well endowed with grants for maintenance of the fabric and support of the college of priests and prebends who worshipped within. Sadly for the choir, after the dissolution the lands and rights that provided its funds and endowments passed into private hands. Maintenance of the whole church by the parish became impossible, so the nave and tower were sealed off, and everything east of the tower was left to decay. Parliamentary soldiers carried off the organ in 1643, the choir roof collapsed in 1696, and the chapter-house followed in 1750. Cotman’s viewpoint is artful, since it is calculated to exclude the tower and the intact parts of the church and present us instead with a wholly exclusive study in neglect. Cotman was not the only artist to take an interest in Howden. Turner sketched the same aspect in 1797. But Cotman put his observations in the public eye, and manipulated his material to emotional effect.

None of Cotman’s on-the-spot sketches of Howden are known today. It was, however a significant subject for him. Perhaps his earliest treatment of the subject is a watercolour at Touchstones, Rochdale.

This records the view of the church from about 300 metres north-west on the road to Selby. Cotman’s view looks back along the rutted road from open country, but is today overtaken by new residential development. Sadly the watercolour has suffered from long exposure to light. It was presumably framed and hung on a sunlit wall for decades, and as a result most of the blue in the sky – predominantly indigo [a cool greyish blue] – and hence almost all of the original atmospheric effect – has faded. Originally this watercolour would have been altogether richer and fresher in effect. Sadly this is an issue which effects much of Cotman’s production from his early years, and indeed a large proportion of watercolours intended for framing and display by all artists from the earlier years of the nineteenth century.

East end of Howden Church, Yorkshire, 1804

Watercolour over pencil;, 456 by 335 mm.17¾ by 13¼ in.

Signed and dated 1804.

Sotheby’s, London, Master Works on Paper from Five Centuries, 6 July 2022, lot 192

Cotman thought the ruined east end of the church sufficiently important that he developed a composition for exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1804 (no.462, as ‘East window of Howden Church’). Cotman’s exhibits are difficult to identify with certainty, but the most likely candidate in this case is a watercolour dated 1804 sold at Sotheby’s in London in 2022. This appears to be Cotman’s earliest treatment of the composition of the etching.

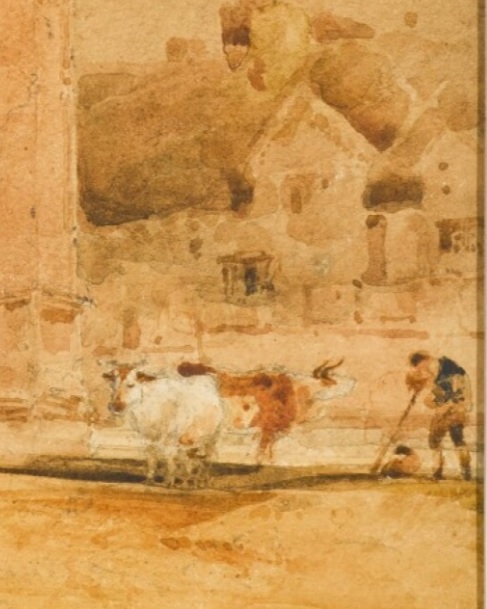

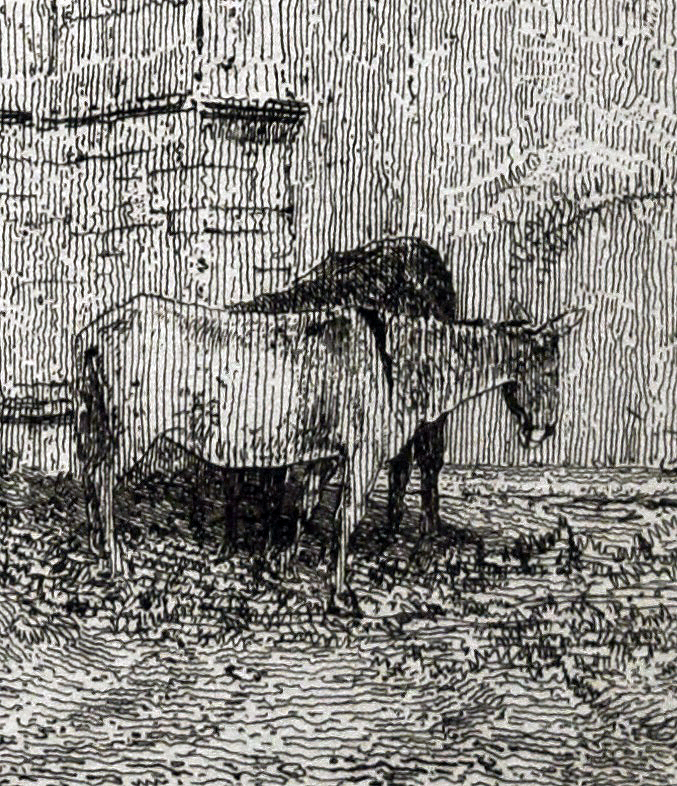

It was one of a trio of operatic architectural subjects exhibited together with Rievaulx Abbey (see plate 8) and Fountains Abbey (see plate 19) all the result of his 1803 immersion in the best of Yorkshire’s antiquities. Each one is a study in bathos, each a triumph of human spirituality reduced to browsing cattle. That does seem genuinely to have been the case at Rievaulx (see plate 8) but at Fountains and Howden it seems to be poetic license: The ruins of Fountains were enclosed as garden, and Howden remained part of the parish church and fronted onto the market place. Nonetheless a reduction to the bucolic seems an apt conception of the contemporary circumstances of these sites, where their original cultural dynamism had fled to industrial and metropolitan centres, leaving behind only a resistant, stoic pastoralism.

All Cotman’s exhibits of 1804 appear to have found buyers. The Howden found an especially appropriate home at Brandsby Hall, home of Cotman’s Yorkshire patrons the Cholmeley family. Mr and Mrs Cholmeley, together with their son Francis, were actually Cotman’s travelling companions when he sketched at Howden in September of 1803. Francis celebrated his twenty-first birthday on 9 June 1804, whilst the watercolour was hanging on the walls of the Royal Academy exhibition, and it might well have seemed a most appropriate gift. It remained in situ for over a hundred years when Hugh Fairfax Cholmeley, the grandson of Francis, decided on a clear out: ‘The watercolour of Howden Abbey church (a ruin) by Cotman was hung in the dining room till lately. It was much faded, spoilt by damp and not a very good picture so I sold it for £90.’ The date of this memoir is 1908 when £90 was a considerable sum. A basic inflation calculator puts it as the equivalent of about £15000 today. It passed to William Allan Coats (1853-1926) of Dalskairth House, Dumfriesshire, and remained there until 2022 when offered at Sotheby’s in London. Faded or not, the £1764 realised at the sale looks rather like a lack of appreciation.

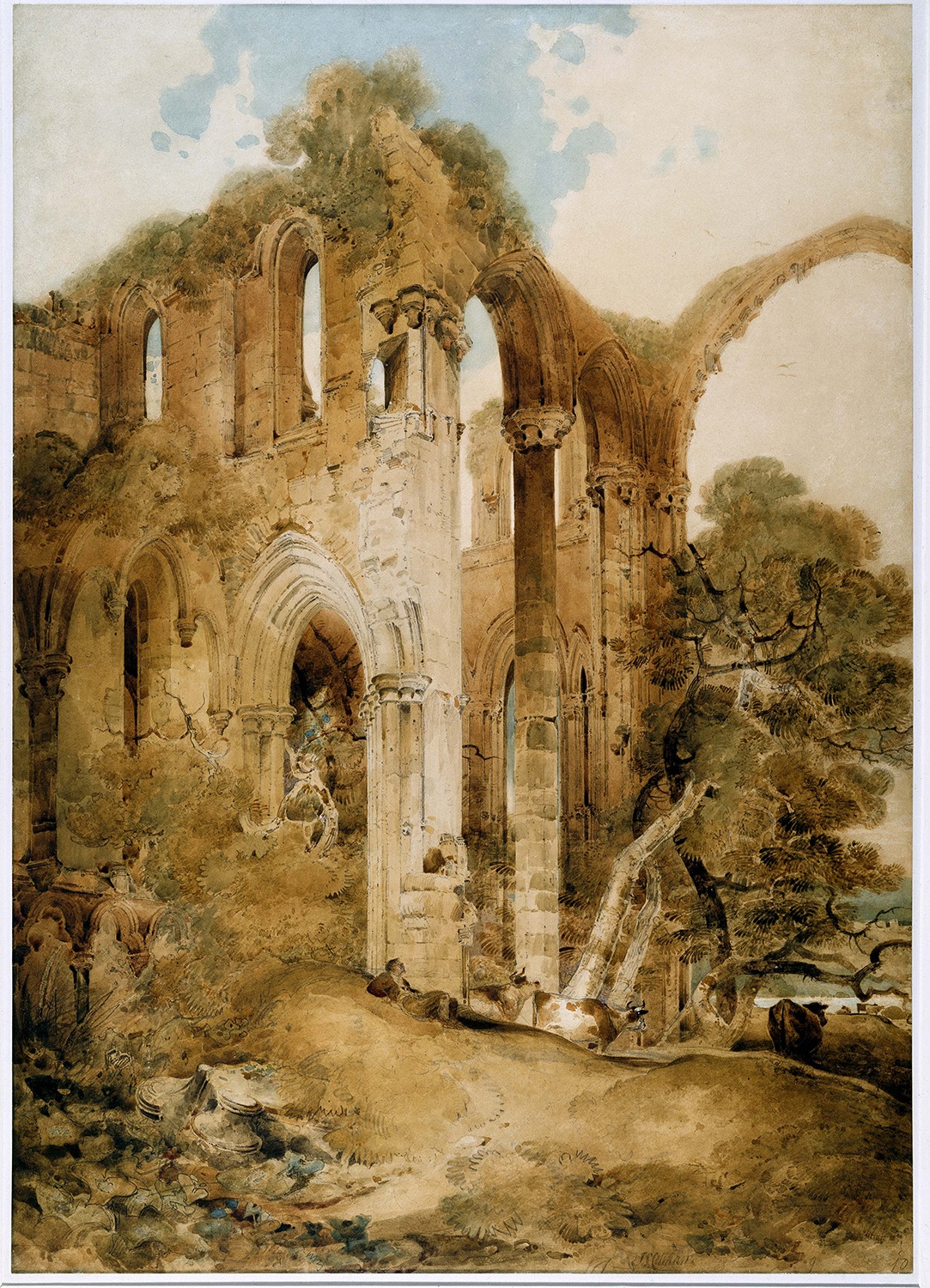

East end of Howden Church, Yorkshire, date unknown

Watercolour, 440 x 325 mm, 17 5/16 x 12 3/4 ins

Dunedin Public Art Gallery, New Zealand (144-195X)

Reproduced by courtesy of Dunedin Public Art Galle

A second version of this composition is to be found at Dunedin Art Gallery, New Zealand. I have not seen this in person, but the gallery has supplied a high quality digital image. It was given to the gallery in the 1950s by Archdeacon Smythe [see Sippel 2023 in References below], and although described at the time as ‘the finest collection of water colour pictures in the Southern Hemisphere’ many of the attributions from that time have not survived contemporary scrutiny. On the basis of the supplied image, the Dunedin watercolour appears to be a close copy of the Sotheby’s watercolour. It is almost exactly the same size and follows the detail assiduously. It does, however, appear to preserve its colour a little better, offering crisper definition and a refined opposition of ochres and grey. It offers nothing, however, of Cotman’s characteristic bravura of draftsmanship or dobbed-in, painterly, fluidity. The difference in hands is most clearly demonstrated in the treatment of the cows and herdsman, where the weakness of the copy is most evident.

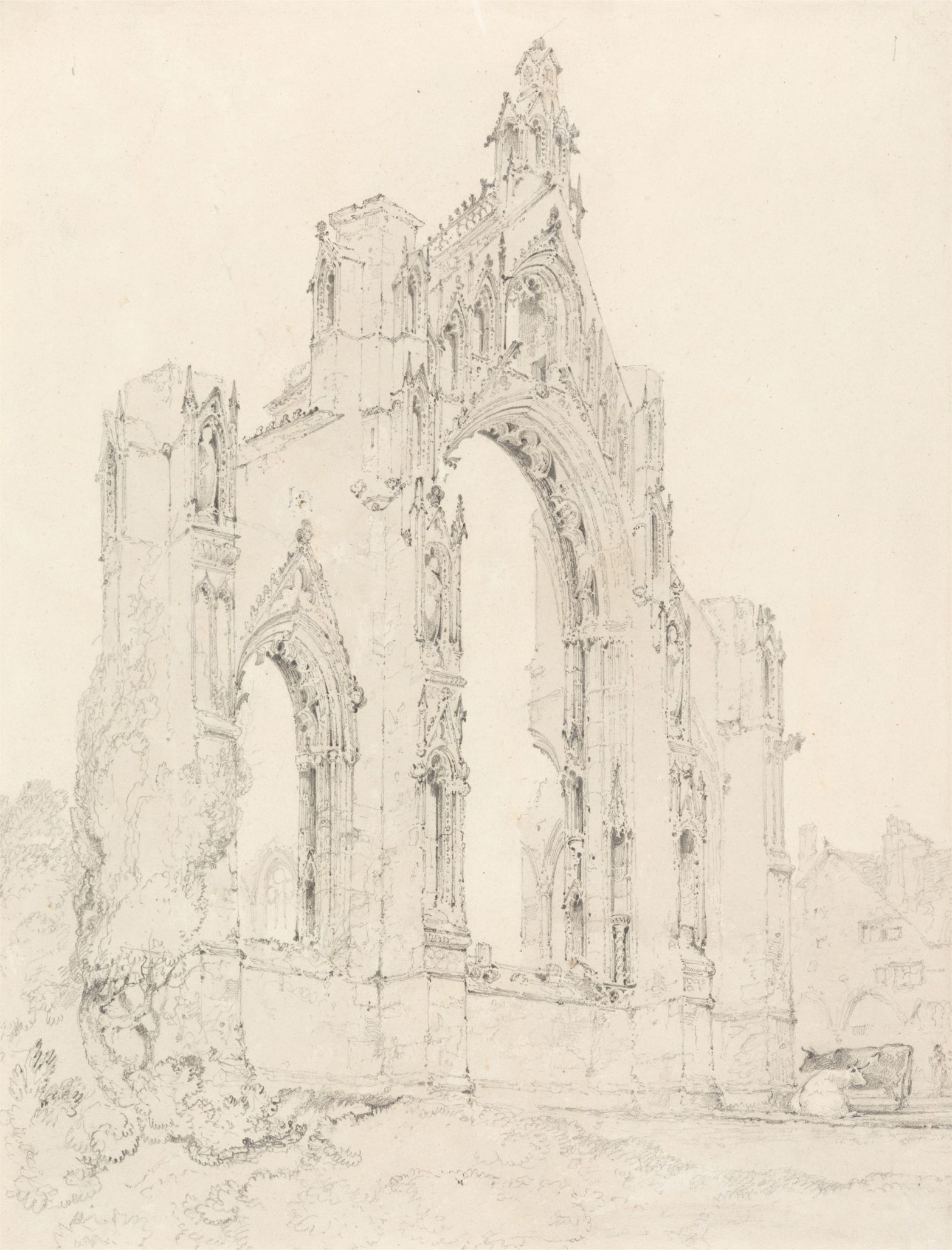

Cotman’s next treatment of the subject is a pencil drawing at the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven.

East end of Howden Church, Yorkshire, c.1810

Graphite and white wash on off-white paper, 15 5/16 x 11 3/4, 396 x 298 mm

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut, USA, B1975.2.507

This is one of a group of studio pencil drawings that Cotman developed in the years after 1804. In this case the pencil reassimilates every detail into a bravura performance of sensitive, refined and elegant draftsmanship. Cotman’s original on-the-spot sketch of Howden does not appear to survive, but we can see an analogous process at work between the on-the-spot sketch of Crowland and its corresponding studio drawing (see plate 22 #1 and #2). Here, Cotman supresses material at the side and in the background to concentrate the attention exclusively on the façade. He emphasises the care, perseverance and invention that has gone into its conception and execution, and likewise into the wonder with which all that has been traced in the drawing. Overall he gives the structure a sense of fragility, and of persistence despite abandonment.

There are several related drawings, including one of Fountains Abbey dated 1804, which appears to be the earliest, and is perhaps less refined than the others, together with Rievaulx Abbey, Crowland Abbey, and St Mary’s, York. Of these Crowland and Rievaulx seem especially close. It seems likely that the pencil drawing of Howden was made in Norwich sometime after Cotman’s removal there from London in 1806. He made a major push to establish himself as a drawing master in grand style, including holding an exhibition in his studio of over five hundred drawings – which must have been almost his entire stock in trade. Large, demonstrative, drawings such as this were calculated to impress, and perhaps even astonish, and to be judged by some considerable measure beyond any other artist in the city, or even the land.

Cotman regarded Howden as one of his key discoveries in 1803, and his watercolour hung in pride of place in the home of his Yorkshire patrons the Cholmeley family. He must have spoken of the subject with some pride for when he discovered Crowland the following year (see plate 22) he wrote to his Yarmouth patron Dawson Turner, ‘you know how I esteemed my Howden. This Oh this is far, far superior.’ In 1810 the two subjects became the twin poles of Cotman’s series of etchings.

On 20 December he could report to Francis Cholmeley: ‘I am now about Howden. Croyland is finished but I have had no proof, therefore cannot say how it will turn out.’ Two weeks into the new year he wrote again with specimens of both Crowland and Howden: When my prospectuses were ready I waited daily to send you an impression or two of Croyland, but weeks passed from a mistake of the printer’s before they were sent down. In the meantime my Howden was in a great state of forwardness, and so great a delay would hardly feel an extra few days.. so I have sent you specimens.. when you have satisfied your curiosity resecting their demerits and merits, I shall esteem it an additional favour to have them sent to the most respectable book or print seller in York. Should you think my specimens worthy of your criticisms, I shall be proud to be favoured with them, as a fresh eye (to my misfortune) may with ease detect the tottering state of my poor Howden, caused by too strict attention to parts, and rather too much care have been taken with the shadows for the good effect of the whole. Croyland proves a more perfect work, though not so perfect as I hope to render it some time hence, as well as Howden.’ The Howden proof survives with descendants of the Cholmeley family, but as we have already heard (see plate 22, part #3) that of Crowland was sent up to Edinburgh to attract subscriptions there. Cotman finishes this account with an insight into his choice of dates for publication: ‘Croyland bears the date of my wedding day [26 January 1811 – his second anniversary] and Howden that of the birth of my boy [Miles, Edmund, born 5 February 1810, so dated to his first birthday]’. He presumably hoped that such auspices would bring the project good luck.

Francis Cholmeley responded frankly to Cotman’s invitation to feedback: ‘Howden alas! Tho’ excellent in other respects, not only totters but tumbles’. Indeed the whole gable above the arch leans forward perilously. It is an undoubted error, deviating from the perpendicular by up to five degrees. The Sotheby’s watercolour and Yale pencil drawing are fine, and Cotman, as we have seen, was already aware of the defect before he sent his proof to Cholmeley. He replied on 5 March to explain how the error had come about, and incidentally offer an important glimpse into his ambitions:

Howden I can’t hold up against such truths as you advance against it. The perpendicular [was] lost by my applying a three inch lens to the work… I gained … [?nuance] and lost the general effect. Difficulties … into effect is the general test of merit in every branch of profession or conduct. The man who takes the most desperate leap, bears the bell [an expression for winning a race] from the man who has rode all his life without a fall. The style I have adopted is more difficult than that style of the Manor House [one of his earliest, see plate 2], which is made up of scratches. [In] the other style [i.e. that of Howden] every line is studied and is decided, consequently more calculated to shew talent.

The mistake must have irked him, but it is remarkable that he decided not to rework the plate. But his response to Frances Cholmeley also implies that he regarded it, as it stood, as an important document of his character, and his willingness to attempt the greatest difficulty. We have had occasion to suspect as much in other instances, but Cotman’s remarks here do prove that he intended his etchings, and by implication his work in general, as exemplars of moral conduct.

The information that he worked on the detail through a three-inch lens demonstrates how close an interest Cotman took over the smallest detail, and the finest line. We might also wonder whether he masked off all but the area on which he was working. That would prevent accidental scuffing, scratching or rubbing of the ground, but limit his view of the relationship of that part to the whole. Applying the same lens we can readily appreciate what a density of touch and affect is achieved. As with all of Cotman’s drawing his hand traces a uniquely sensitive, thinking engagement with his subject matter. If Cotman’s intent was to elicit a concerned admiration for the ruins themselves, in the end the tottering and reeling only exaggerates the effect.

Perpendiculars apart, Cotman did find the surviving ornamentation in much better condition than it is today. He records most of the mouldings as well-defined, the canopies over the windows and niches still intact, even down to the slender finials rising from the upper corners.

Compared to that the whole face now seems melted as if made of butter. It does, however, appear as if conservation work began early. Cotman shows three surviving statues in the niches, one top left and one each side of the main window. An engraving by J P Neale shows that by 1812 there was only one statue remaining in situ left of the window. Now there are none, but all those shown by Cotman appear to have been removed to the interior of the church and have survived in reasonable condition. Their confinement must on the whole be a good thing in terms of their preservation, but they were designed to look out on the world and to maintain watch over our management of their legacy, It is perhaps not for the best that their view has been severely constrained.

Cotman introduced new figures into the etched composition, and before finishing, we should give them some consideration. The three men are more than merely generic. That at the left is a stocky fellow, probably middle-aged, and well-dressed in a fedora and dark coat. His stance appears balanced and purposeful, but his white stockings and lightweight shoes suggest an indoor milieu. He carries a wooden board. In Cotman and the North, I speculated that this might be for supporting a drawing or notes, but with the perspective of another twenty years another thought now occurs; that it might be for sitting. In the middle of the group is what appears to be a younger man, wearing a light-coloured riding coat, equipped with a capacious hood. His short black boots suggest some preparedness to encounter less well-made ground. Finally the figure at the right is perhaps older than either, and dressed in a cap, three-quarter coat and trousers. Most intriguingly, as I observed first in Cotman in the North, he is plainly black, and might well be a manservant to one of the others. In any case the figure does invite the viewer to give some consideration to the wider situation regarding such figures. Slavery was a major political issue in the first decade of the nineteenth century, and in 1803 the Cholmeleys and Cotman passed through Hull, the home town of William Wlberforce the leader of the anti-slavery movement. In Cotman and the North I speculated that the two men at the left might represent Francis Cholmeley Senior, of Brandsby Hall, and his son Francis. Cotman visited Howden with both in 1803. It would have been by no means unusual for the Cholmeleys to have employed a black groom, but I have not yet been able to find any documentation of this in the Cholmeley archive at the North Yorkshire County Record Office in Northallerton. Perhaps more diligent eyes might find something. In reviewing what notes I have to hand now, however, I am struck that in the letter to Francis Cholmeley of 20 December 1810 in which he mentions that he is ‘now about Howden’ Cotman specifically mentions one of Francis Cholmeley’s servants: ‘Your servant James is a fine old man’, Francis must have spoken about him in a previous letter. Whatever the explanation, the figure here is a striking and unusual detail that certainly warrants further elucidation.

In the earlier treatments of Howden Cotman favoured the inclusion of cattle to signify a certain stoic pastoralism. By the time of the etching, however, donkeys had overtaken cattle in Cotman’s affections, and were a frequent motif in his compositions. In a previous discussion (see under plate 6, St Mary’s York) I suggested that perhaps there was more than a little self-identification involved. Donkeys are a traditional emblem of patient, uncomplaining service, generally under-appreciated or rewarded. Despite some implication that the donkeys are to be associated with the figures, that is difficult to sustain in practice. Gentlemen such as these would have travelled by carriage or on horseback. Donkeys carried goods for tradesmen, and these were no doubt put to work at the market or round the town. Just as his style was intended to shew talent, so Cotman’s details were intended to be considered. If the gentlemen represent former times for Cotman, the donkey might more have represented the present, wondering whether his constant application, would indeed be rewarded with appreciation or reward.

Summary of known states:

Proof before publication

Line etching, image (max) 370 x 274 mm (14 1/2 x 10 3/4 ins) on plate 382 x 279 mm (15 1/8 x 11 ins) printed in black ink on soft, heavyweight, off white, hand-made rag wove paper, sheet size approx. 475 x 350.

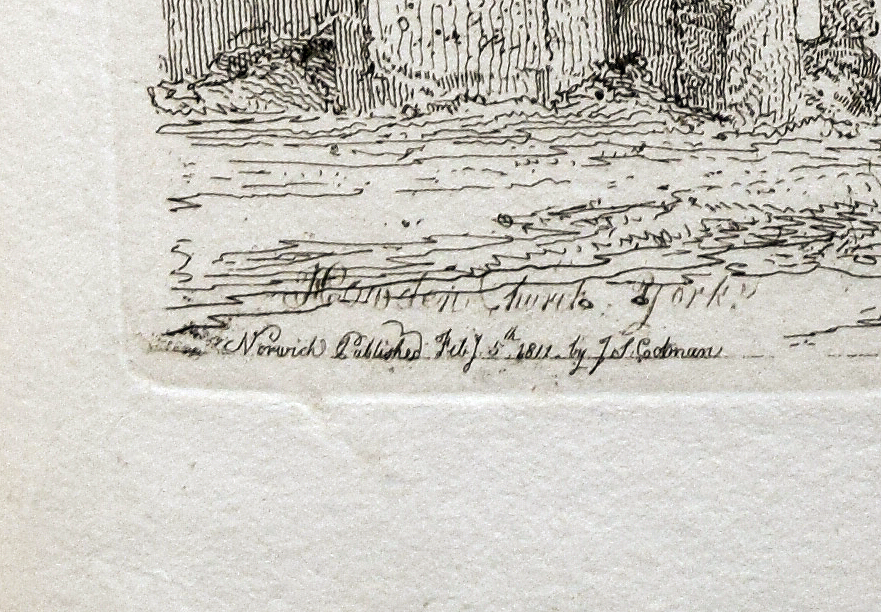

Inscribed on plate below left along edge of image, in a small and firm script: ‘Norwich Published Feb y 5th 1811 by J S Cotman’ and lower right, almost illegible against the other line-work, ‘Drawn and etched by J S Cotman’.

Differs from the first published state only by the omission of the engraved title.

A poof impression sent to Francis Cholmeley in the possession of a descendant. Inscribed in ink by the artist ‘’East End of Howden Church Yorks’ and ‘To Francis Cholmeley Esqr with J S Cotman’s Respectful Compl:’

First published state

As editioned by Cotman for ‘Etchings by John Sell Cotman’, 1811, where plate 23.

Line etching, image (max) 370 x 274 mm (14 1/2 x 10 3/4 ins) on plate 382 x 279 mm (15 1/8 x 11 ins) printed in black ink on soft, heavyweight, off white, hand-made rag wove paper, 474 x 340 mm

Inscribed on plate lower left. ‘Howden Church Yorks’ and below on margin line, in a smaller and firmer script than that above: ‘Norwich Published Feb y 5th 1811 by J S Cotman’ and lower right, in a third hand, almost illegible against the other line-work, ‘Drawn and etched by J S Cotman’.

Collection: Examples in various collections, e.g. Norwich Castle Museum NWHCM : 1956.254.25

Second published state

Line etching, image (max) 370 x 274 mm (14 1/2 x 10 3/4 ins) on plate 382 x 279 mm (15 1/8 x 11 ins) printed in black ink on heavyweight ?machine-made wove paper, 493 x 353 mm

As editioned by H G Bohn in ‘Specimens of Architectural Remains in various Counties in England, but especially in Norfolk. Etched by John Sell Cotman’, 1838, Vol. 2, series 4, i. Plate unchanged from 1811 edition except for the numeral ‘I’ added top centre.

Examples in numerous collections, e.g. Norwich Castle Museum, NWHCM : 1923.86.25

References:

A.E.Popham, ‘The Etchings of John Sell Cotman’ [an introduction and a list] in The Print Collectors’ Quarterly, 1922, pp.236-273, no.25.

David Hill, Cotman in the North, Yale University Press, 2005

Adele M Holcomb, John Sell Cotman in the Cholmeley Archive, North Yorkshire County Record Office, 1980 [Transcribes references to Cotman in Letters and daybooks]

Stephen Lonsdale, The Marshland Minster: A Biography of Howden Minsterc.650-1548, University of York MA dissertation, 2019, available online at (99+) The Marshland Minster: A Biography of Howden Minster | Stephen Lonsdale – Academia.edu

Annika Sippel, A forgotten collector: Archdeacon Smythe and his collection of British watercolours in New Zealand, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa research papers, available online at www.tuhinga.arphahub.com

Thanks for the reference to the Annika Sippel’s research article on Archbishop Smythe – I see she did her PhD on him and his donations to New Zealand. After just a brief glance through the article I see it has an illustration of a cottage that is ascribed to Cotman, but certainly is not. I am with you in thinking the Howden watercolour is accurate but not Cotman. Sippel states that there are 24 works ascribed to Cotman in the New Zealand Te Papa and Dunedin museums from the Smythe collection, one of which, the fine St Julitta’s Capel Curig church interior (dated 1803) was noted by Kitson in 1928 (Cotmania vol 3, p81). As Tom Girtin observed (Sippel), just occasionally Smythe got one right!

I presume you must have observed the strong compositional / colour relationship (as well as sad faded condition) between the Rochdale Howden and the Ely Cathedral c1804 (Bonhams 6 July 2022, lot 27) – based on the pencil drawing at Leeds and which you note as untraced in your Leeds catalogue entry.

Jeremy