Photograph by David Hill, taken 2 May 2018, 12.05 GMT

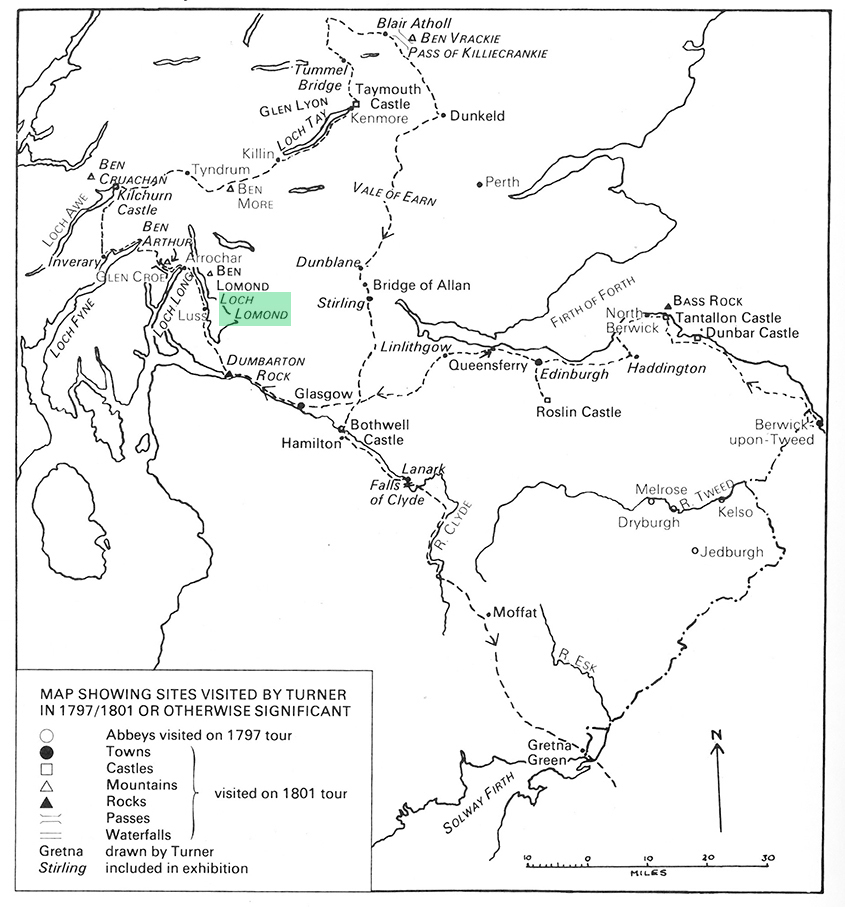

This article returns to a subject briefly visited in an article of 10 April 2016 in which I discussed a Turner watercolour of Ben Arthur from near Arrochar. I had not time then to investigate the subject in any detail, but finally last week managed to visit the exact spot. Regular readers will know that I find wild goose chases hard to resist. This involved searching for a roadside detail that appears have been entirely forgotten. As it turned out the specific search proved fruitless, but the visit did enable me to exactly photograph Turner’s general view, and to make a surprising discovery about his selectivity.

Loch Lomond from Colonel Lascelles’s Monument near Inverbeg, 1801

Pencil on paper, 149 x 218 mm (page size, 149 x 109 mm) from the ‘Tummel Bridge’ sketchbook, Tate, London, D03282-83, Turner Bequest TB LVII 3a-4 as ‘A Wooded Cliff beside the Old Military Road along Loch Lomond, with the Loch and Ben Lomond to the Right’

Image courtesy of Tate. To see the image in the Tate’s own online catalogue, click on the following link, and then use your browser’s ‘back’ button to return to this page:

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-a-wooded-cliff-beside-the-old-military-road-along-loch-lomond-with-the-loch-and-ben-d03283

Photograph by David Hill, taken 2 May 2018, 12.56 GMT

The sketch is a double-page spread from near the beginning of Turner’s ‘Tummel Bridge’ sketchbook at the Tate. He used the book on a tour of Scotland made in 1801. He was already 550 miles into the journey when he took out the book at Glasgow. He had journeyed north via Yorkshire, Durham and Northumberland to Edinburgh and Glasgow. His subsequent journey took him up the west shore of Loch Lomond as far as Tarbet, and then across to Inverary, back east through Tyndrum to Loch Tay, and then as far north as Blair Atholl before returning south through Stirling, Lanark, Moffat and Gretna to the English Lake District. This sketchbook records Turner’s first entry into the Scottish Highlands.

Scanned from exhibition catalogue of ‘Turner in Scotland’, Aberdeen Art Gallery, 1982

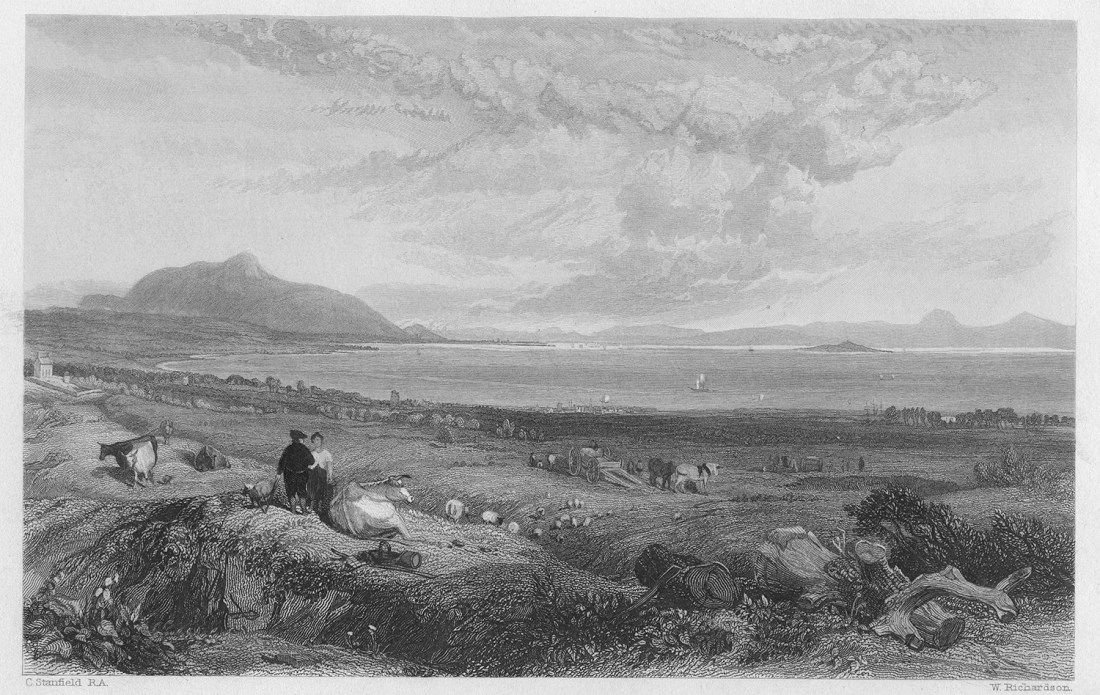

The few previous pages are quick snatches of scenes, probably made on the hoof, but this is the first to set down a scene carefully. The atmosphere appears still and hazy for the mountains are reduced to flat silhouettes of tone.

In many ways the subject represents a return to familiar ground. In previous years Turner had developed his sense of mountains in the Lake District and North Wales, and Loch Lomond presented him with a well-rehearsed composition of mountains seen over water. The subject must have registered with him, nonetheless, for he developed it into a more elaborate ‘finished’ pencil drawing in a series of fifty or so ‘Scottish Pencils’. These appear to have been made to be mounted in an album as an elaborate prospectus to be shown to prospective patrons who might commission a finished treatment in watercolour or oils.

Loch Lomond from near Inverbeg, 1801

Gouache and graphite on paper, 345 x 492 mm

Tate, London, D03380, Turner Bequest, TB LVIII 1 as ‘The Road along the Western Shore of Loch Lomond, with the Tablet to Colonel Lawless on a Rock, and Ben Lomond in the Right Distance beyond the Loch’.

Image courtesy of Tate.

To see this image in Tate’s own online catalogue, click on the following link, and then use your browser’s ‘back’ button to return to this page:

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-the-road-along-the-western-shore-of-loch-lomond-with-the-tablet-to-colonel-lawless-d03380

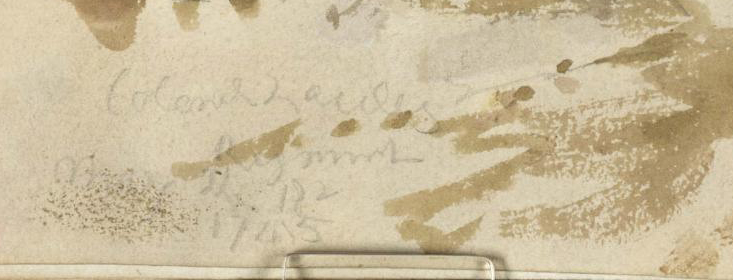

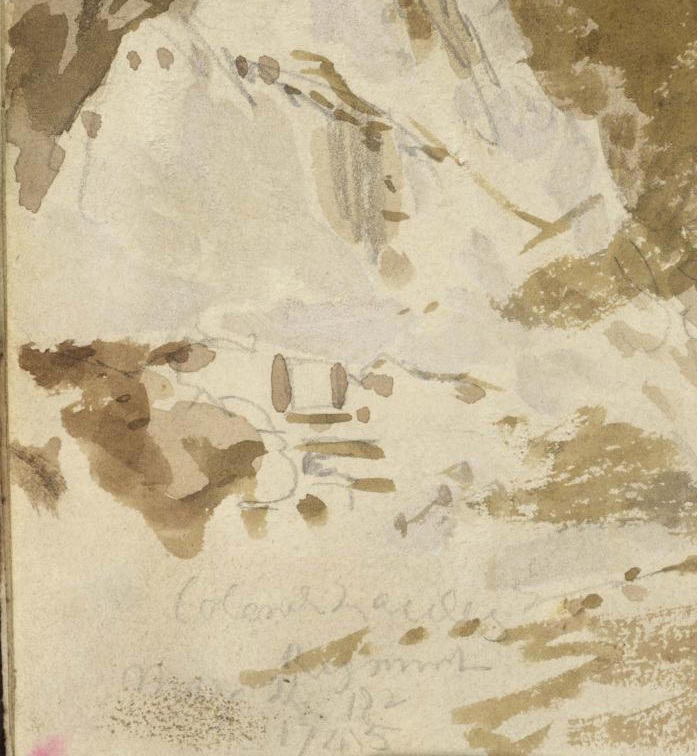

In this case, however there was an element that provided him with a specific occasion. The original sketch is inscribed at the bottom left: ‘Colonel Lascelles/ Regiment/ May the 18th/ 1745’. The name has previously been transcribed as ‘‘Colonel Lawless’. The Colonel in question is rather Peregrine Lascelles (1685-1772) born in Whitby and in 1743 appointed Colonel of his own Regiment of Foot, the 58th, later renumbered as the 47th. One of his regiment’s first deployments was to forge the new military road up the west shore of Loch Lomond, part of a new route from Dumbarton to Inverary. This was the first proper road along the shores of Loch Lomond. Previously goods, animals and people would have traversed the lake by boat. The inscription that Turner recorded presumably recorded the completion of this particular stretch on 18 May 1745.

Turner would have been immediately drawn to the name of Lascelles. The Lascelles family, Earls of Harewood in Yorkshire were Turner’s major patrons at this time, and Turner might easily have assumed a connection. The Lascelles had in recent years commissioned a number of substantial and expensive works from him, and Turner might have hoped that this was a subject with direct appeal. Although some connection does seem likely – the family has deep North Yorkshire roots – I have not yet managed to establish any link between the Harewood and Whitby branches of the family. Whitby Museum has a portrait of him by Godfrey Kneller, and there is a fine memorial to him in Whitby Church.

Turner would also have been struck by the date on the inscription at Loch Lomond. 1745 is the year of one of the key historical events of the eighteenth century, the rising of Bonnie Prince Charlie in the second Jacobite rebellion. Colonel Lascelles’s regiment had been raised in Scotland in 1741, and when Lascelles was appointed commander in 1743 its troop had no battle experience. Their military function here was to extend the routes of communication across which soldiers and their equipment could be deployed in the highlands, thus consolidating the jurisdiction established after the first Jacobite rebellion in 1715. Shortly after the soldiers had dated their memorial here, however, on 19 August Bonnie Prince Charlie raised the Stuart standard at Glenfinnan.

Photograph by David Hill, taken c.1985

The regiment accidentally found itself on the front line of a war and on 21 September faced the Highland army at Prestonpans, not far east of Edinburgh. The English army was small, almost completely inexperienced and was routed. Lascelles was left deserted on the field, and although captured and disarmed was somehow allowed by the Highlanders to proceed on his way.

Battlefield of Prestonpans, 1842

Engraving

Published as an illustration to edition of Sir Walter Scott’s novel, Waverley, Edinburgh, 1842.

In 1801 the Jacobite rebellion was still a relatively recent memory and the Lascelles monument on Loch Lomond seems to have been a well-known and conspicuous landmark and recorded at least twice by contemporaries.

The first is by a literary figure almost equally illustrious as Turner. Dorothy Wordsworth visited the spot during a tour of Scotland in 1803 in the company of her brother, William and the equally esteemed poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge. On Wednesday 24 August she made an evening walk with William from Luss and recorded this spot in her ‘Journal of Recollections’ (Carol Kyros Walker (ed), Dorothy Wordsworth: Recollections of a Tour Made in Scotland (1803), Yale UP 1997, pp.119):

We called to mind with pleasure a seat under the braes of Loch Lomond on which I had rested, where the traveller is informed by an inscription upon a stone that the road was made by Col. Lascelles’ regiment. There, the spot had not been chosen merely as a resting place, for there was no steep ascent in the highway, but it might be for the sake of a spring of water and a beautiful rock, or, more probably, because at that point the Labour had been more than usually toilsome in hewing through the rock.

The following year the historian James Denholm published a ‘History of the city of Glasgow’, including ‘A Tour to the principal Scotch and English Lakes’. He also noticed the Lascelles monument;

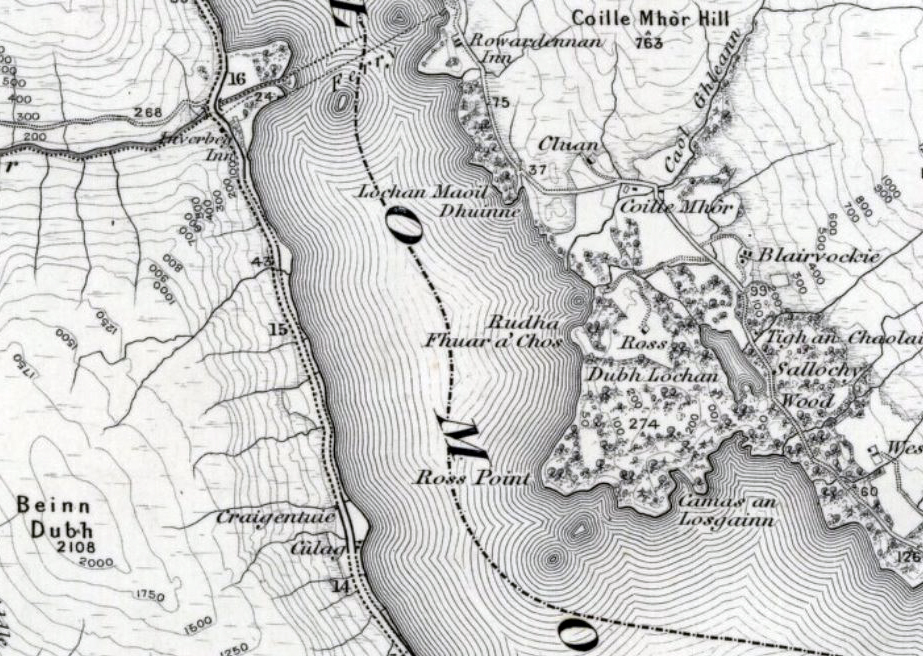

One particularly useful of Denholm’s account is that it fixes the situation of the monument very precisely at the fifteenth mile stone. The mile stones are marked on the early large-scale Ordnance Survey maps, so it is possible to narrow down the location very precisely.

http://maps.nls.uk/view/74488742

It puzzled me that no more recent reference to the monument presented itself, so I contacted the Dumbarton Museum to ask if there was any record. Rather to my surprise, the staff there had never heard of it and seemed sure that it has never been listed in the archaeological record. Rather ominously, I learned that the road (the modern high-quality A82) had been considerably improved and widened in the 1980s, and this had involved much blasting of the lochside to create a new fast carriageway. Had they known about it, the blasters would presumably have at least recorded the monument and perhaps even preserved it in a nearby location. Slim chance, perhaps, but it was in hope that it had somehow escaped that I resolved to at least take a look.

But what exactly was I looking for? Turner’s depiction of the monument – possibly the only visual record ever made – requires some careful scrutiny. Denholm describes an ‘Inscription cut on the rock upon the left’ and Dorothy Wordsworth mentions ‘a seat under the braes’ as well as ‘a spring of water and a beautiful rock’. Denholm seems to imply that the inscription was cut into the native rock, and at first I imagined a large inscription carved into the rock face.

So armed with the precise location of the fifteenth mile stone, and some idea of the quest, I parked up in the car park just south of the location. It is easy to map the old OS map to the contemporary topography, for the streams running into the loch are very easy to locate. Each forms its own beach of pebbles where it discharges into the loch. The modern car parks on the loch side are at Firkin point – the shingle to the right, and at the unnamed shingle to the left of the Google Earth detail. The site of the fifteenth miles stone was just above the stream that issues into the loch between them.

Photograph by David Hill, taken 2 May 2018, 12.56 GMT

Just above stream outlet marking the fifteenth mile post, the road levels out for half a mile before Firkin Point. From the footpath by the loch the opposite side of the road comes clearly into view. It is all now screened by the shrubby growth of hazel and birch, but in the first week of May was still visible through the buds of leaf. Beyond the Armco barriers and broad tarmac there was no sign of any fifteenth mile stone but near where it must have stood was a south-facing rock face of almost exactly the same proportions and shape as in Turner’s sketch.

I should not, perhaps recommend this to anyone else, but waiting for a gap in the traffic (and believe me, the road is of ample quality to facilitate speeds approaching ninety miles an hour in some drivers) I managed to effect a crossing, and wriggled my way through the trunks and branches on the other side. The rock certainly looked comparable to Turner’s, and was covered with moss, but no amount of scanning, or scraping of moss would reveal any inscription. Rather discouragingly, all around and underfoot were signs of disturbance. Shattered rock was everywhere, spread six feet deep or more to make the roadbed above the loch, and heaped up like blown leaves at the foot of the crag. I walked the roadside for a couple of hundred yards in each direction, but to no avail.

So, disappointment. The blasters appear to have destroyed it. There is, however some slight hope remaining. Musing over Turner’s sketch and Dorothy Wordsworth’s account, a remote possibility remains. Dorothy Wordsworth speaks of a ‘seat’, and closer inspection of Turner’s sketch serves to support the idea. He shows two steps leading up to a single-seat recess, and the inscription was presumably carved on the back of the seat. One thought did occur to me on site, and that was that the native rock here is a heavily foliated schist. A pretty rock, but not ideal material in which to carve an inscription. It occurred to me that the inscription might have been carved in contrasting material, perhaps the fine sandstone that occurs further south around Glasgow. It also occurred to me looking at Turner’s drawing in the light of what I had found, that the modern road level is several feet higher than that built by Lascelles’s regiment, and that the seat apparent in Turner’s sketch might not have been destroyed so much as buried in the scree of the modern roadbed. Perhaps this is not quite a strong enough argument for digging quite yet, but enough not to discount its survival entirely.

The trip was worthwhile in any case for the general view that Turner recorded, and as it transpired the subject was not quite as previous cataloguers and myself had assumed. The Tate’s new catalogue of the Turner Bequest calls it ‘A Wooded Cliff beside the Old Military Road along Loch Lomond, with the Loch and Ben Lomond to the Right’. This seemed uncontroversial until I stood at the sight and realised that Turner had not included Ben Lomond at all.

In Turner’s sketch the highest peak at the right is that of Ptarmigan (731m). The actual summit of Ben Lomond (974m) is beyond the right edge of the field of view. This seems to want some explanation, for surely we might expect Turner to include the prominent summit of the titular mountain of the region. The explanation might be as simple as the summit being obscured by cloud. While I was pondering this a couple of cyclists from Glasgow, making their way up the Loch Lomond cycleway towards Tarbet stopped for a chat. It was a splendid clear day. ‘Look – Ben Lomond’, one said, ‘We don’t see that very often’.

But conditions in the sketch appear to be good. The flat haze of the profiles of the mountains seems to be that of a still humid day rather than a cloudy one. It seems more likely that Turner’s cropping was intentional, and designed to give the composition a sense of immediacy and of involvement. It is a well-known property of photography that the more one attempts to include, the more staged, stilted and detached seems to be the result.

Either way, as he made his way northwards, Turner had plenty of opportunity to study the mountain, and to make a number of sketches and more finished works.

It might be nice to give some space to thinking about those in more detail. Hopefully on another trip…

There is a celebrated portrait of Mary Chaloner Hale as Euphrosyne, one of the three Graces, by Sir Joshua Reynolds, who also painted her husband. It now hangs in Harewood House, the home of her sister Anne, who married Edward Lascelles, 1st Earl of Harewood. The John and Mary Hale memorial is in St Nicholas Church, Guisborough. My pic of it here https://www.flickr.com/photos/bolckow/5725330291

Thanks for this, but is there a link here between Harewood and Peregrine Lascelles?