This is the third of a series of articles exploring Cotman’s association with St Benet’s Abbey, Norfolk. Part 1 and Part 2 looked at Cotman’s early treatments of the subject, and here we discuss an etching published in 1813. Without doubt, this can be considered as one of the masterpieces of his entire career.

[On a desktop, click on image and select ‘open in new tab’ to view full-size. Close tab to return to this page]

Cotman made this engraving for inclusion in his series of ‘Architectural Antiquities in the County of Norfolk’. The plates were issued from 1811 in groups of six. Cotman, as usual, found numerous distractions and diversions, and publishing proceeded erratically until sixty were published as a single volume in 1818. This appeared in 1813 as the first plate of part five.

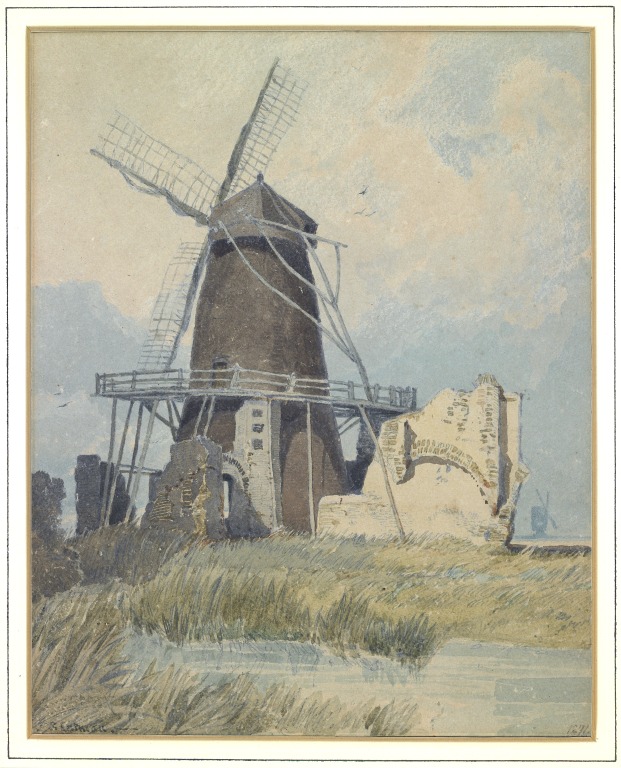

Most subjects were selected for their antiquarian interest, and several have mostly only antiquarian interest. St Benet’s, it has to be said, is a building of extremely incidental architectural or antiquarian interest. The historical remains are those of the abbey’s former gatehouse – the abbey buildings being completely erased – redeveloped in the eighteenth century as the site of a windmill, initially built to grind rape seed, and then sometime in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries adapted as a wind pump to lift water from the surrounding grazing land into the river Bure. Even Cotman must have recognised that the composition was an aesthetic triumph. Scholars have wondered ever since that he so readily allowed himself afterwards to be pulled away from his strongest ground.

Technically it is among the best of all his plates. Perfectly bitten; exhibiting an exhilarating variety of drawing and mark-making, and unique amongst the Norfolk Antiquities etchings for the degree of elaboration of its skyscape. With a shower blowing in from the east its concept seems completely pictorial, and a release into space after being close quartered in most of the subjects thus far. In character St Benet’s steps completely outside the antiquarian confines of the project as a whole, and it seems likely that the composition was initially conceived as an independent artistic development, possibly an exhibition watercolour, or even an oil painting, that was happily pressed into service in the Antiquities. In any case, the composition is one of the high-watermarks of his first maturity.

[On a desktop, click on image and select ‘open in new tab’ to view full-size. Close tab to return to this page]

The remains of St Benet’s Abbey stand on a marshy plain near the junction of the rivers Ant and Bure about ten miles directly ENE of Norwich. It is much further by road, south of the village of Ludham, and requires some perseverance to reach it in a car, lurching and splashing down an uneven field road. It is easier to reach by water, being only a short distance from the Bure, and serves as a prominent landmark for river traffic. Cotman records it from the south, not far from the river bank.

[On a desktop, click on image and select ‘open in new tab’ to view full-size. Close tab to return to this page]

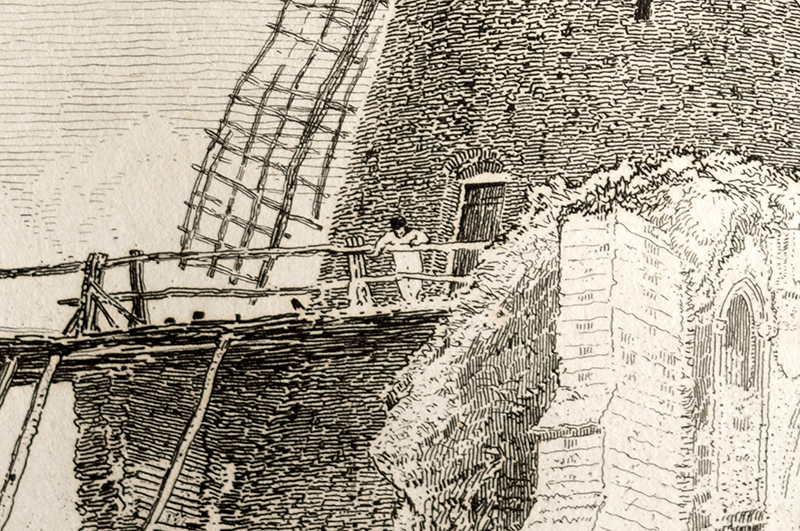

There are, however, some issues relating to the topographical detail of the composition. Although the angle on the gatehouse is that from the south, the angle on the body of the windmill is that from the south-west.

An earlier watercolour at the Lady Lever Art Galley, Port Sunlight, records the south-west aspect completely consistently, showing that Cotman has transposed the detail of the mill there onto new material giving the gateway from the south.

The key element of this is a doorway (an attractive artistic detail in the engraving, with the miller standing on the landing outside) which faces west, and is invisible from the southerly viewpoint.

There is also a subtle adaptation in the etching of the detail of the mill in the earlier drawing. The turning pole has two long spars that spring from low down the pole and attach to the frame at either side of the cap. Cotman records the structure meticulously in the earlier drawing, but eliminates the furthest spar in the etching, presumably to simplify that detail, and give the timbers a stronger graphic presence against the sky.

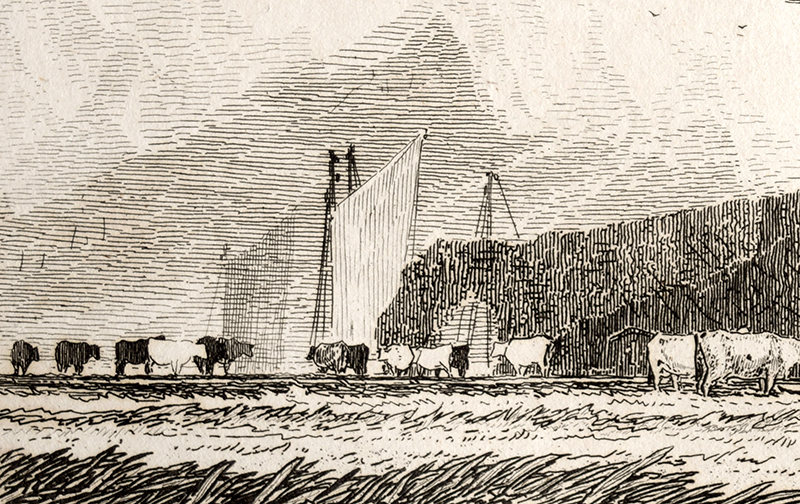

A few other details distinguish the engraving. At the left Cotman introduces a few sails belonging to barges gliding by on the River Ant. In fact the Ant is nowhere near so close as Cotman’s composition implies. It gives a magical effect, but in truth is inspired invention.

The effect is also dependent on being imagined from an exaggeratedly low viewpoint. In reality the observer would have to be lying face down on the ground to bring the horizon so low and thus maximise the silhouette.

One final detail demonstrates the way in which Cotman routinely sustained his concentration even down to the slightest of details. We might notice that the crown finial has been knocked askew. He might well have found that empathetic. A grand edifice being knocked about by events.

[On a desktop, click on image and select ‘open in new tab’ to view full-size. Close tab to return to this page]

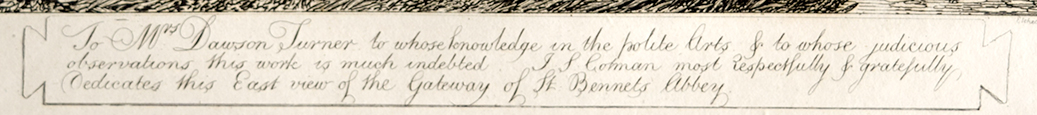

Finally I do have to acknowledge, as if these angles of view were not complicated enough, that Cotman, in titling the plate and dedicating it to his patroness, Mrs Dawson Turner, described his view as from the East. What can I say; left/right; west/east; they are just too easy to confuse. I do it all the time.

TO BE CONTINUED: Precursors and derivatives

I have failed once more to cope with the online facility – so I am composing this response then entering it onto your site…..

I congratulate you on your analysis of the St Benet’s etching – a masterly (and expected) mix of on-the-spot observation / viewpoints and knowledge of the artist’s approach and technical ability. Not having visited the site / subject I can only applaud your exposition.

Of course I have to note a couple of things – the distant mill to the right of the main subject: much further off in reality might possibly relate to (Top) Heigham mill (on the map you show), a post mill – Ludham mill (also shown on your map) was a tower mill. A mill possibly features in Henry Bright’s oil of the St Benet’s abbey / mill subject (see NCM Henry Bright,1986, (cat. 3, ill.) – but only discernible as a faint ‘tower’ in reproduction.

The bent nature of the ball finial that you note atop the mill in JSC’s etched depiction of the mill is equally depicted as bent by john Thirtle in at least two of his drawings – NCM Thirtle cat. (1975) Nos 23-4, Pl. 15. Francia (Higgins) and others straighten up this detail – not so observant perhaps?

An incidental observation: The platform which you explain as accommodating the lengths of spars supporting the cap of the mill, might also be explained as constructed to give access to the sails / vanes at the lowest point of their revolution (they exist on tower mills with no supporting spars). They are seen on examples in many parts of the country – but I only have a summary, if exemplary, text to refer to: Rex Wailes’ Windmills in England (1948, reprinted 1975) – it does have readily understandable descriptions / illustrations of the construction / mechanisms of the different types of windmill. I agree that the Romantic Windmill catalogue is well worth perusing – sadly, gone is the day when such thematic shows were readily funded.

Hi Jeremy

Thank you for the feedback and additional information. I have certainly wondered about the distant structure to the right of the etching. Cotman seems to want us to look into it. After all, he went to the trouble of including it. I’ll see whether my photos picked anything up on the horizon. Thanks for pointing out the necessity of the staging to allow the miller access to the vanes, though to judge from the state of these vanes, he hasn’t been too assiduous in attending to their maintenance! Am hoping to carry on to look at some depictions by cognate artists in a later part. There are some fine efforts. The Henry Bright you mention is probably the most dramatic.

Just a slight addition to the possible distant ‘mill’ to the right of Cotman’s mill tower – in the Miles Edmund drawing, ‘Ludham St Benet’s Abbey (Norfolk)’ (Norwich NWHCM 1951.235.702.B28) a faint indication of what appears to mill sails is visible in the horizon (?). The drawing has none of his father’s bravura but might be more straightforward observation – certainly no surrounding trees – and rather small scaled boats on the river.